A hot summer

Emotions, policing and the state of Britain

I'll explain the photo later. For now, here's a teaser question: is that a truncheon in the officer's holster or is he just trying to please us?

It's been a very hot summer. By this I obviously don't mean the weather, which has been cloudy even by British standards. I'm referring to the riots and the first weeks of the Starmer government, both of which have implications that extend far beyond the season.

In this Substack, I won't be discussing the riots themselves other than to say that everything in my world, from my intuition to a variety of external sources, tells me they are not as they have been presented by politicians and the mainstream media. But they sit at the centre of a number of related issues, some of which require urgent attention from those who care about Britain. I realise many people won't have kept up with the rapid pace of developments over the holiday period, so what follows is part commentary and part summary offered as a kind of catch-up.

It's worth stressing, in these highly partisan times, that my writing comes from a non or post-tribal perspective. Since 2020 I've learnt some hard lessons about the importance of observing actions rather than words and the need to see things as they are rather than as I would like them to be.

I Talk about foreigners

For some time I've been troubled by a new kind of talk I've been hearing about foreigners and immigrants in Britain. Expressing hostility towards whole groups of people by reason of their ethnicity or religion, they’re uncharacteristic of the tolerant country where I've been fortunate to live most of my life. While it’s most prevalent on social media, this kind of talk can't be dismissed as a purely online phenomenon – I know some of the people involved personally and have heard similar attitudes expressed in face-to-face conversations.

Such attitudes are very different from concerns about immigration policy. Policy is, after all, just a bunch of practical decisions about collective living. Small communities, such as those I've been a part of during August and nation states alike have to decide on policies, from limiting ticket numbers to rules about camping. But that doesn't mean you have to think that, of and in themselves, certain groups pose a collective threat. The new xenophobia even applies to immigrants who've been here decades, raising the question: was this hostility running under the surface all along? Or is it more that the negative feelings we all have are being harnessed to serve a certain agenda?

It's also been disappointing how some of those in the truth/freedom movement made an immediate decision to align with Israel after the events of October. I have considerable experience of the Israeli/Palestinian conflict and the emergence of these new certainties took me by surprise. When I worked in this area in the early 2000s, people were, if anything, over-reluctant to engage with the complexity of Middle Eastern politics. But at least they knew what they didn't know. Now people who are clearly uninformed hold very strong opinions about the situation – views which conveniently echo the position of government and other powerful interests. This discussion between Gareth Icke and Dan Astin-Gregory captures some of the issues.

This turn in public sentiment illustrates the power of human emotions and how they can lead us – and be used by others to lead us – into situations we wouldn't ideally choose. A personal case study helps me understand the otherwise inexplicable attitudes of Britain 2024. In a conversation some fifteen years ago, my late mother made an uncharacteristically hostile remark about 'immigrants'. Surprised, I reminded her she'd been married to an immigrant – she brought my father into the country herself – for nearly fifty years. My mother seemed surprised by this fact and defended herself on the grounds that her cleaner didn’t like immigrants either.

We left it at that, with me quietly concluding that my mother's ill-health had laid her open to the temptation of negative emotion. Perhaps a similar thing is happening on a national scale now. The emotion in question is anger, which is perhaps inadequately understood. Portrayed and feared as a destructive force and often subject to suppression, anger is a natural and healthy part of being human. Rooted in frustration or a instinctual rejection of danger or injustice, it's key to our ability to say 'no'. Anger becomes unhealthy when stuck and dangerous when projected on to the other. And then it can become the emotional mechanism that underlies scapegoating.

As Greg Braden points out, there is a close relationship between emotions and choices:

'Every moment, every day of our lives we are making choices … and here's the question we all need to ask: Are we making those choices from the love of what we know is possible on our lives or ... from the fear of what happens if we don't? What are we becoming in the face of the challenges that we see and is it what we want to become? Or is the narrative and the mainstream media driving us to become something that we would never choose to become – vengeful, angry, hateful, divisive people? When we see that, those are the cues which will guide us to make the choices from love rather than fear.’

So my first takeaway from the Hot Summer of 2024 is to do with emotions and how, unless we are very conscious of them, they can lead us into some very undesirable places.

II The police and the people

In the wake of the riots, a national discussion of a different kind erupted. This concerned two-tier policing and whether protests were being treated differently depending on whether they were in line with the view favoured by government.

The Economist explained that this 'conspiratorial belief' was untrue, the Guardian characterised it as a 'myth' propagated by 'the far right' and the Times as a 'fallacy' which had fuelled the riots. So far, so familiar: since 2020 I've been watching open-jawed as, one after another, publications I respected abandoned any attempt at journalistic integrity and published material clearly designed to promote a state-approved narrative. A common tactic is for an outlet to take an issue being talked about, label those expressing alternative views as 'far right/conspiracy theorists' and then deny that the issue has any foundation whatsoever. Sometimes this process is called 'Fact check'.

But this summer, other media outlets, from independent media to established conservative organs, have been examining the issue of two-tier policing in a way I recognised as genuinely journalistic. I'd been sitting on my own firsthand experience of the issue since 2020 when I'd observed the Met's gentle tolerance of the Black Lives Matters protests in central London and then their aggressive approach to those protesting Covid restrictions.

I broke my holiday to write a piece about this for the Spectator which was praised by the commissioning editor and generated some fan mail. What a glorious relief – such was the pressure to conform to a single prescribed viewpoint four years ago that I’d kept quiet about attending a lockdown protest. Finally, people – influential people – were realising that something was rotten in the state of Britain. Here at last, amid all the collective amnesia and denial, was the beginnings of a public debate.

The issue at its heart could hardly be more serious. It concerns the relationship between people and police, a defining feature of British democracy. In contrast to the paramilitary forces in many European countries, British police derive their legitimacy from the consent of the people. Their job gives them no superior status for, according to the code on the Home Office website, ‘the police are the public and the public are the police’. Their role requires that they 'seek and preserve public favour' and operate impartially, without 'fear or favour'. And, rather than follow the commands of political leaders, as happens in police states (and in the UK in 2020-21) they must uphold only the law created by the legislature, ie Parliament.

How strange that the Metropolitan Police Commissioner Sir Mark Rowley – the highest-ranking officer in the land – should feel entitled to manhandle the microphone of a journalist asking a question. It was a gesture of contempt for both the media and the public, and technically constituted assault. The question about two-tier policing was asked as Rowley was leaving a meeting in Downing Street.

Meanwhile, the Prime Minister used the riots to justify plans for a national roll-out of facial recognition. So far and controversially, the technology, which involves checking the faces of passers-by against a database of people on a ‘watch list’ drawn from any sources without the consent of the individuals involved, has been banned by the European Parliament. Identification mistakes are sometimes made and the process is known to carry racial bias. But British police are very keen on using it. South Wales Police have continued to use it a ruling from the Court of Appeal that it violated privacy rights and broke data protection and equality laws. The Metropolitan Police are increasingly using it on the grounds that it makes us more ‘safe’, with police in Newham continuing to surveil people in the borough despite a unanimous vote by councillors to suspend its use.

Why are government and police so keen on facial recognition? Surveillance is central to control over a population. Talking to people in Albania for the book that eventually became Spyless in Tirana, I came to understand the deeply corrosive effects of surveillance. By the end of the regime, as many as one in three people worked for the secret police, informing on their neighbours, fellow workers and family and the national psyche has yet to repair. “People learned to keep things private and secret, especially thoughts: your thoughts are always secret,” Ana Stakaj, the women’s programme manager for the Mary Ward Loreto Foundation, told me. The effects were long-lasting – more than thirty years after the communist regime finally crumbled into a basic form of democracy, I could see that people were still distrustful of each other.

Now, in the West, we are kidding ourselves if we allow ourselves to fall for reassurances that increased surveillance is just about safety or that new initiatives to watch us and monitor our behaviour will stop 'there'. “There is a very instinctive drive to expand surveillance,” says Carissa Véliz, an associate professor in psychology at the Institute for Ethics in AI at Oxford University. 'Human beings like seeing more, seeing further. But surveillance leads to control, and control to a loss of freedom that threatens liberal democracies.”

A couple of years ago I got talking to a Syrian exile in Lisbon. An actor and luminously bright man, he told me something I struggled to believe: the Assad regime, which routinely imprisoned and tortured its critics in the early 2000s, had since expanded its network of control. A Syrian living in Paris had been overheard making a joke about the government. When he returned to Syria to visit his family, he was immediately arrested. No criticism, even on foreign soil, could be tolerated.

My second takeaway from the summer: despite all our knowledge of history and lip service about the dangers of fascism, in Britain we have yet to learn the lessons of the recent past.

III The rise of the new censorship

'I've never seen freedom die so quickly as it has in the UK in the last month,' Canadian journalist David Krayden told Neil Oliver.

It's strange for me, instead of observing authoritarian features of other countries from a comfortable British perspective, to be hearing international voices expressing alarm at the anti-democratic turn taken by the cradle of liberal democracy. My YouTube feed is suddenly full of entrepreneurs advising viewers to 'leave the UK NOW'.

One of the new government's first responses to the unrest was to try to stop the public discussing it. Director of public prosecutions Stephen Parkinson announced that even a retweet could be a crime if it reposted a message deemed to be false, threatening, or 'likely' to stir up racial or religious hatred. 'We do have dedicated police officers who are scouring social media,' he said softly. 'Their job is to look for this material.'

‘Think before you post’ threatened the Crown Prosecution Service on X. It was the tone that got me – headteacherly, but freighted with intimidation worthy of The Godfather. Is that a way to address the citizens who elected you?

The threats were followed by a spate of arrests for a new kind of crime. Bernadette Spofforth, a businesswoman and mother-of-three was arrested by Chester police ‘on suspicion of publishing written material to stir up racial hatred’ and ‘false communication’. She had incorrectly alleged in a tweet, with the caveat 'if this is true', that the killer of the three little girls in Southport was a Muslim asylum seeker.

An example was probably being made of Spofforth, who happens to be a vocal critic of government policy such as lockdowns. She was released on bail after intensive interrogation by the police 36 hours later.

But others – modest folk who probably haven't had the kind of attentive parenting and education that teaches you discretion and emotional regulation – were sent straight to jail. Jordan Parlour was sentenced for 20 months after calling on yobs to destroy a hotel housing asylum seekers in Leeds. Lee Dunn got eight weeks for sharing three images of Asian-looking men with captions such as ‘Coming to a town near you’.

It's hard to overstate the significance of the territory we have entered when people are being put behind bars for saying inaccurate, daft or unpleasant things. The imprisonments have been made possible by section 179 of the Online Safety Act which came into force in January. And the full powers of the legislation have yet to manifest. It’s not due to come fully into force next until next year while Ofcom – which has form in censoring information about Covid and vaccines – draws up guidelines for social platforms.

The state is seeking yet more control. Sadiq Khan used the civil disorder to call for the Online Safety Act to be revisited and toughened up, something Starmer lost no time in agreeing to do. It looks likely that ministers will be seeking to impose duties on social media platforms to restrict content they deem 'legal but harmful'. This loose, catch-all formulation could be interpreted any way the authorities see fit – and crucially it removes the legal basis for freedom of speech.

Meanwhile, some are agitating for Ofcom to be given 'emergency powers' to demand 'immediate action' from social media platforms in 'times of crisis'. The idea is part of a raft of proposals developed by the Centre for Countering Digital Hate following a discussion with government officials and the Metropolitan Police’s Counterterrorism Unit. The proposals from the CCDH include covert ways of controlling public debate such as 'addressing advertising and commercial incentives behind disinformation' – basically more of the shadow banning, manipulation of algorithms and de-monetising that we've seen on YouTube and Facebook in recent years.

Who is this tank-think which craves so much influence over what we can say? We don't really know – its website just says it's funded by 'philanthropic trusts'. But this short video with its founder and CEO Imran Ahmed reveals a lot about the character of its leadership.

Even before the riots, curtailing free speech seemed to be a priority of the new administration. One of the government's first decisions was to halt the implementation of the Higher Education Freedom of Speech Act due to come into effect in August. To the dismay of many academics, Education Secretary Bridget Phillipson said the act would place ‘too much of a burden on universities’.

The Home Office is considering banning prayer outside abortion clinics. This despite the consequences of West Midlands Police arrest of Isabel Vaughan-Spruce on suspicion of silent prayer outside a clinic in Birmingham – an apology, £13,000 compensation courtesy of the taxpayer and the case being included by the US Commission on International Religious Freedom in its annual list of violations of religious freedom around the world.

The Home Secretary is also pondering measures to allow the police to spend more time on 'non-crime hate speech' such as calling of an 11-year-old boy a 'shorty'. Scotland already has a new hate crime law, a comically messy piece of legislation which has swamped the police with complaints about things that other people may have said in their own homes. What's most significant about these developments is how they cross a line, the first moving the authority of the state internally, to the province of the mind, the second entitling it to regulate what citizens say in private.

It’s important to remember that, despite its acceleration, the drive for more censorship is not new or confined to Labour. As Molly Kingsley points out in this summary on Twitter, the UK's state censorship operation has ‘been in full swing for at least three years’. You tend to notice if you've been on the receiving end, as has she, the co-founder of children's campaigning body UsForThem, or if, like me, you're a citizen keen to do your own research and make up your own mind.

The writer Ayaan Hirsi Ali captures the very different feeling of the Britain in which I grew up: “When I came to the West in 1992, free speech seemed a settled issue. From defamation to fraud, perjury to libel, insult to incitement, the legal limits were largely decided … The British were proud of their new-found free speech, including their tolerance for lèse-majesté and blasphemy. Think of the impotence of the BBC’s ban on the Sex Pistols’ ‘God Save the Queen’ or the success of Monty Python’s Life of Brian.’ As a child I remember my mother defending me from attempts by the vicar to curtail my reading and explaining that Speaker's Corner was a place where people could say what they liked, even if it was mad. And yet here we are in 2024 rapidly travelling in the opposite direction.

Ultimately, of course, the attempt to censor human expression is futile. It is not possible for government to retain permanent control of what people, in all their emotionalism, creativity and diversity, think and say. Even before censorship breaks down and society remembers that openness is best, people find ways around state control. In the 1580s, Thomas Greenwood (possibly one of the non-conformist ancestors I wrote about in The Secret Life of God) became a leader of an independent Christian church called the London Separatists. Arrested for sedition, he and a fellow preacher continued to write in prison, pushing manuscripts between the bars, from where they were shipped to Holland for printing and then smuggled back into England.

Even now in China, where the state is steadily eroding anonymity on the internet, an 'ingenious grassroots resistance' is developing in which people are finding ways around online censorship. And now that the internet has been invented and the world is full of people with computer skills, it’s only a matter of time before new cyber-networks spring up.

But societies can lose years, generations, while they re-learn this lesson, times which bring suffering to those who speak out and suffocation for everyone else. And there's a caveat to my statement about the impossibility of permanent control. Where there's a will, there's a way, but what if all of us were to lose the will – otherwise known as the human spirit – which has so far prevented tyranny from taking a permanent hold? This is a point for the threatened essays on transhumanism, but it needs to be acknowledged now. Digital technology offers those with power unprecedented means of control, while artificial changes to our bodies, once in place, could spell 'game over' for humanity.

IV News about Palestine

A couple of days before I heard what had happened to Sarah Wilkinson, on a video call with my Lebanese friend I joked that I might soon be seeking political asylum in Lebanon.

I used to be a part of the world in which Wilkinson, a British activist reporting on the Palestinian Territories, lives. In the early 2000s I went regularly to the West Bank and Gaza, first as a volunteer English teacher, then as a journalist and finally as communications manager for Christian Aid. I wrote pieces about what I witnessed for the Guardian and the BBC, among other publications. In Britain, I had many friends and contacts concerned with the plight of the Palestinians, including the late Jeremy Hardy. I tell you this by way of reminder how fast the world has changed, as well as to convey my understanding of the context of what follows.

Early on August 29th Wilkinson found several vanloads of police officers, some armed and wearing balaclavas, about to break down the door of her home in a Shropshire village. The counter-terrorism police officers refused to show her ID and ransacked the house, including the attic, where they emptied the urn containing her mother's ashes. They took many of her possession, including money and her passport, without listing them in the normal manner and hid other of her possessions around the house in a manner that can only be described as malicious. They handcuffed her tightly and drove an unnecessarily long way to the police station, the van throwing her around and causing injuries. At the police station she was interrogated for posting 'online content' and refused the medication she needs to manage Crohn's Disease.

Wilkinson was released on bail on condition that she does not touch any electronic devices including a phone, even in an emergency. She cannot travel, even to buy food but has to report regularly to the police station. When she mentioned that the journey is so long she will be unable to get home the same day, the officer laughed and told her to 'take a tent'. In any case, the passport she needs to present is gone and as a result she believes she will be imprisoned for breaking her bail conditions.

I encourage you to watch this interview with her.

Wilkinson believes she is being set up, using the counter-terrorism legislation, for imprisonment without trial, potentially for up to 14 years. This segment from UK Column provides some useful context about the Terrorism Act, although it doesn't answer all questions about the legal basis for such a situation. The story has not been reported by either The Guardian or the BBC.

Some observations:

- Wilkinson's arrest and treatment by the British authorities is a clear indication that the state is trying to suppress dissent and information which counters the official narrative. As Jonathan Cook says in his Substack: 'the police are using the Terrorism Act in this way only because they have received political direction to do so. Wilkinson’s arrest is only possible because the police and Starmer, supposedly a human rights lawyer, are rewriting the meaning of the term “support for terrorism”. This is political repression in its clearest form.'

Along with the arrest of British-Syrian journalist Richard Medhurst under the same legislation, it also constitutes political persecution of individuals.

- Several times in her account, Wilkinson compares the behaviour of the police to that of Israeli security forces. They demanded to know, for example, the names of Palestinians she deals with and the location of wells being installed by the charity she supports. This is consistent with what I and others experienced when travelling in and out of the Palestinian Territories: the Israeli security forces would routinely ask for names. We knew what would happen to anyone we told them about.

All of this raises the question of who Britain's counter-terrorism police are really working for.

Incidentally, Sir Mark Rowley is a former head of the counter-terrorism police.

- While listening to Wilkinson's account, I had the same response I always have when hearing of corrupt or barbaric behaviour. It's an internal voice which addresses the perpetrators with something like this: don't you realise that what you are doing is being witnessed, and will come to be widely known? It’s something that may have developed while I was doing research on the Nazi holocaust as part of my PhD and read many witness accounts by survivors of the concentration camps, from Primo Levi to little-known authors. All the accounts exemplified the same powerful impulse: the need to bear witness. The Nazis well understood this impulse, and sometimes tormented their victims with the promise that 'the world would never know' what happened to them.

We know how that worked out.

V How to respond to Now

Long-standing readers of this Substack will know that I'm not big on denial – my tendency lies more in the other direction, towards hyper-vigilance which, in societies where denial is prevalent, fosters something of a Cassandra complex. But I confess that, listening to Wilkinson's account, I struggled to believe that what she described was happening on British soil. First coming across the interview on UK Column where it was introduced by someone based in Damascus, my psyche seized on this fragment of information to reframe Wilkinson's treatment as something that took place in Syria. Perhaps the British authorities were involved but Syrian security forces carried out the arrest? Much more likely! Of course that interpretation wasn't consistent with the facts, so I had to revise my ideas about what was possible in my native land.

Other ways I could have denied the reality of what I heard include:

She made it all up. British police couldn't have behaved like that

She's a criminal and deserves whatever happens to her

It's a one-off – some sort of unfortunate mistake which can be sorted out

Notice that, while no 1 involves discrediting Wilkinson's account and character so as to leave the status quo intact and no 3 avoids considering the matter at all, no 2 goes much further. It involves abandoning values and principles which have underpinned life in Western society for longer than our lifetimes, essentially asserting that, come a certain circumstance, the state has the power to do whatever it likes. Such a position involves a transfer of loyalty of the kind identified by Erich Fromm and other social psychologists as they sought to understand why so many turned against freedom in the totalitarian societies of the twentieth century. It’s a shift away from self to authority, a self that includes one's own self, loved ones and the people in wider society.

I've already seen some of these psychological manoeuvres on social media with respect to Wilkinson’s arrest, and fully expect to hear them in a personal conversation. Whatever form they take, they’re an attempt to avoid uncomfortable truths, expressions of denial which Stanley Cohen, in States of Denial, points out is a common and natural human response in the face of atrocities and suffering. At the same time, it’s what allows and creates such situations.

So the first part of any response to what’s going on is to step beyond denial, a response rooted in the emotion of fear, and to start seeing what is.

From a position of clarity, reactions come naturally. They might come strong, like Crispin Flintoff's declaration in his interview with Wilkinson: ‘If they want to come for me, they can come for me too. Everyone's got to fight for you as an example. I will not shut up.’

Responses vary from person to person, from situation to situation. For some, they might involve supporting some of the organisations gearing up to stop Britain's slide into tyranny. They include Together, formed in 2021 in response to attempts to impose vaccine passports and mandates and Big Brother Watch, which has some advice on what to do if you are wrongly identified by facial recognition cameras.

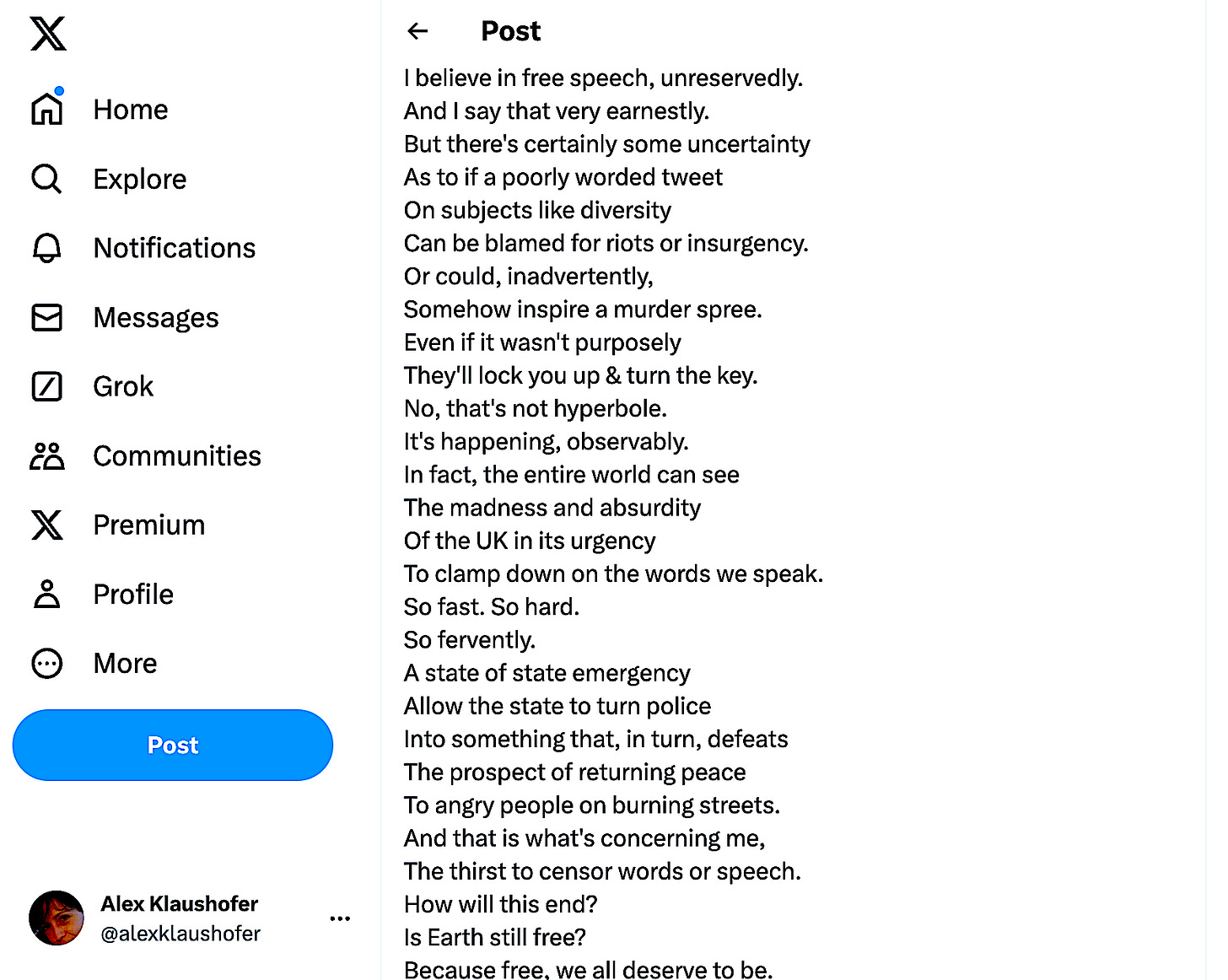

They might involve lighter, more creative approaches. Amid all the memes of 'Comrade Starmer' on social media, there's been some impressive poetry:

Responses can come small and quiet, without any forethought. Last week I passed two police officers in my local park who bid me 'hello'. Historically I've felt well-disposed towards the police, regarding them as public servants who were there to protect me. But this time I could not bring myself to reply. My reaction was a sign of my loss of trust in the British police, something which could amplify into non-compliance if necessary.

And when I saw the men in the photo at the top at a festival this summer I felt a shiver of unease. Why were the police here?

It turned out that they were please officers, professional entertainers hired by the festival organisers who understood their demographic. They were there, they told me, to PLEASE the public and would do a cartwheel on request. I asked them about facial recognition and they pleased me by telling me that they forgot all encounters with the public the instant they were over.

I'll end this essay with recommendations of pieces by two other Substackers which speak to the need to balance awareness with positive response. As David McGrogan outlines cogently here, Britain is entering some very difficult times as the government tries to impose its will on a population that is becoming increasingly angry - some sort of breakdown seems inevitable. Meanwhile, as Rebekah Barnett writes from Australia, we need to find creative, spiritual and humorous ways of living the times we find ourselves in.

And if you fancy a musical antidote, I recommend the final track from the musical ‘Hair’. It starts with shouting and a militaristic beat that creates a dark undertone. But the people start singing 'Let the sunshine in'. They keep singing and, by the end, that’s all you can hear.

UPDATE ON SARAH WILKINSON: most of her bail conditions have been lifted, following recognition that they were inhumane. The police have now admitted that they took her passport.

This was largely due to the huge outcry on social media and elsewhere about her treatment, demonstrating that we *do* have the power to stop wrongdoing when we choose to use it.

https://x.com/swilkinsonbc/status/1832753916481605780

I think the hardening of attitudes to illegal immigrants is because the public can see they're contributing to overpopulation and overload of public services, such as health and benefits. In addition, it's reported that illegal immigrants are getting better treatment than the increasing numbers of homeless people (and pensioners?).

Then we have the "two tier policing" which seems to favour certain ethnic and social groups. Indeed, there's a generalised anger which is also due to more people becoming more short of money and unfairness to the general public enshrined in recent legislation. The recent acceleration of State control, including free speech and surveillance is appalling. People are fed up and feel increasingly threatened and fearful.

Also, the police appear to be increasingly used as a means of enforcing political ideology rather than their real purpose of challenging crime. As you suggest, people who disagree with the Government narrative are referred to as 'far right/conspiracy theorists'. This government is particularly intolerant.

It would be most useful to learn about "ingenious ways" for people to protect themselves from persecution. We need a manual on the subject.

Digital control is indeed a convenient method of controlling people. This is why I support individual online privacy measures so strongly. I've written about this in detail elsewhere. Also, the erosion of privacy in general transfers power from the individual to corporate entities and the State. It amazes me that people in general are so naive and apathetic about this.

I've heard a lot about "Orwellian", and so have recently read the two George Orwell books below; they can be downloaded in pdf or epub format:

https://archive.org/details/GeorgeOrwells1984

https://archive.org/details/AnimalFarmByGeorgeOrwell

Click the three small dots.

I was surprised how many parallels there are between "1984" and what is now happening.