This short video shows a vision of one of the futures, possibly the near-future, that could evolve out of where we are now. A young woman goes about her day with the help of her smartphone. It's a bit like that drawing which changes according to how it's viewed: a bistable illusion. You look at it one way and you see a young, elegantly attired woman. Look at it another and it’s an old woman with a hooked nose and a grave expression. Progress or dystopia? To give you a chance to watch it and form your own response, I'll leave further comment until later in this essay.

I

One of the most disturbing things about returning to Britain after a year and half’s absence has been the marked increase in automation and digital payment.

It's most apparent in central London and around transport hubs. One Sainsbury’s I entered (and left without purchase) now resembles an airport furnished with confectionary. Customers are corralled into a narrow queuing area, the snaking kind that makes you walk back on yourself, through rows of highly packaged products. At the end, you are directed to banks of self-service checkouts which are largely card-only. In the distance, behind a large plastic screen, someone stands in front of the alcohol and tobacco. Otherwise the only human presence is the black-clothed security man.

Elsewhere, formerly-loved cafes have gone card-only. And everywhere people are paying by waving a card or phone across a device. They include children of about twelve, presumably using their parents’ cards to get what they want. Meanwhile, chains such as Starbucks are testing the public appetite for a cashless society.

In the few months I’ve been back in Britain, surveillance in stores has increased dramatically. Recently cameras appeared in three of my local Tescos above the self-service checkouts. A little larger than a tablet, these screens record the face and movements of the customer close-up. (The photo doesn’t quite capture how intrusive they are because my old-school privacy instincts prevent me from getting too close to my subjects.) Initially, I put the trend down to concerns about shoplifting in south London. But then I walked into the Coop in the Cotswold town where I used to live and found cameras there too. ‘Oh, it’s just security,’ said the shop assistant airily. ‘They’re to stop people leaving without paying.”

I was surprised. Part of the reason I’d moved to the town was the placidity of life among its honey-coloured houses. ‘There has been no crime in Bradford-on-Avon today,’ the local police once tweeted.

These trends have been in the making for some time. A quick internet search reveals that Tesco introduced surveillance over their self-checkouts in 2018, 2020 and 2021, provoking complaints from customers and data protection bodies. The cameras were withdrawn but are now back again: if at first you don't succeed, try, try again … Meanwhile, the Southern Coop has introduced facial recognition cameras into some of its stores and is allowing staff to blacklist customers without their consent.

It seems like it was only five minutes ago that recording people in public was uncool in an anti-democratic kind of way. There were also concerns about how images of children and young people might be used. Researching in Spain in 2019, I was told that taking someone’s photo in public without their permission was illegal. In Britain, while freedom of photography prevails, it has long been considered courteous to let people know if they are being filmed as part of a group and give them the chance to opt out.

Coming from Portugal, where 'nao temos multibanco' (we don't take cards) is frequently seen outside shops and cafes, the UK's headlong rush into digital payment is a shock. In Lisbon, I'd got into the habit of taking out large sums of money from the cashpoint because growing security measures in British financial institutions meant I could lose access to my money without warning. Online payments would sometimes be refused for no apparent reason and, Because Covid, it wasn’t always possible to get through to the bank on the phone. When, back in Britain, I finally got through to the Coop, the man on the line muttered something about ‘settings’. Since yet more security measures in the form of two-factor authentication were being instituted, I asked him what protocols were in place for when someone lost access to their phone. There was a pause. Then he said: 'No one's asked me that’.

One bank's security is another woman's inability to book accommodation and spend the night on the streets of Lisbon.

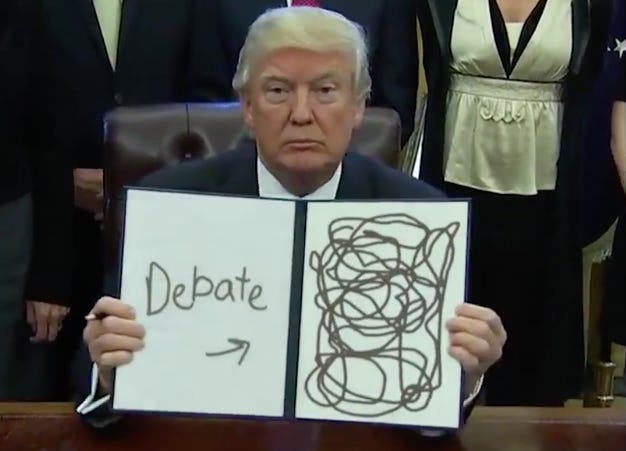

The lack of debate about these seismic changes to the way we live is quite baffling.

The implications of digital dependence are multiple and far-reaching. Foremost is the growing reliance on technology which could fail for many reasons, either for an individual whose phone is lost, broken or uncharged, or for a geographical area suffering a power cut. Without cash, people would have no means of trade. Then there's the exclusion of those who don't have access to banks or cards: Christian the travelling van man who featured in my last Substack told me how recently he'd taken a train to volunteer at a festival. He couldn't buy a cup of tea because they wouldn't take his cash.

For all of us, digital payment brings about a subtle but definite shift in the relationship between buyer and seller. With cash, it’s clear there’s an exchange taking place and it's difficult for the customer not to be aware of what they're spending, at least in their own currency. But with digital payments, the amount is in the hands of the party taking payment. Have you ever okayed a purchase in a gloomy interior without being sure of the exact amount? Or swiped a contactless card not knowing the price? I know I have.

We are told these changes are for our security, will increase levels of convenience and in any case are due to the inevitable march of ‘progress’.

II

Security, Convenience, Progress. What could possibly go wrong?

Quite a lot already has. In 2021, the American public health body the Center for Disease Control bought data from a private company which allowed them to track citizens’ movements through their mobile phones: 'The CDC specifically monitored Americans’ visits to churches and schools, as well as “detailed counts of visits to participating pharmacies for vaccine monitoring” … The CDC also reportedly tracked peoples’ movement during curfews and visits between neighbours.' Canada’s public health agency also purchased data to do the same – and plans to continue tracking the populations' movements for at least the next five years, according to a source in this report.

Defenders of these measures say that the data is always de-identified and only used to track the movement of groups to inform policy. But in the light of the constitutional overreach and deception of many governments in recent years, it is hard to feel sure about this. A Canadian friend told me how someone she knew forgot to fill in a particular form when re-entering the country. The official who stopped him already knew his personal details, including his address and mobile phone number. For many Canadians, the behaviour of the authorities during the truckers’ protest has acted as a wake-up call: bank accounts of people believed to be involved in the protest and those related to them (how did the banks get this information?) were frozen. The police openly threatened protestors: 'If you are involved in this protest we will actively look to identify you and follow up with financial sanctions and criminal charges,’ said the Ottawa police chief.

A temporary response to a crisis? No, such measures are part of a growing trend for the state to gather information about the behaviour of citizens. Typically, governments are doing this in conjunction with commercial partners. A few examples: Ring, the doorbell company owned by Amazon, is in partnership with thousands of police departments in America and has been found to be handing over data about people’s movements without a warrant. (Russell Brand’s take on this is worth viewing for its hilarity alone.) The Norwegian government’s statistics agency is insisting that supermarkets send them daily reports of customers’ purchases. And in England, a new database called NHS Digital now holds the medical records of 55 million patients (unless you opted out via your GP practice).

The information, which includes records of mental health problems, along with every test and prescription, is anonymised to protect patient identity. But this can be reversed if there is a ‘valid legal reason’ to do so. The data can be shared with councils and universities, research bodies and pharmaceutical companies – any body that can demonstrate a legitimate use for it to help improve health policy. The list is long, and presumably grows as new bodies apply for access. You can check the successful applications on the NHS Digital website but it’s hard, amid the spaghetti-like network of partnerships and projects in which public and commercial interests are intertwined, to discern who is doing what, with whom, and to what purpose.

III

Convenience, security, progress?

I want to suggest that these trends are also, and perhaps at their core, about corporate control, lack of trust and something that could be called a process of dehumanisation.

The contracting out of decisions about our daily lives and the things most important to our wellbeing – health, income and relationships – to external bodies has grown exponentially over the past two and a half years. But the shift to greater corporate control pre-dates the Covid crisis and is now moving apace, beyond the realm of public health policy. The myriad ways in which it could penetrate our lives still further is perhaps best illustrated through That Video. But first, a confession: I’m not remotely in two minds about its significance: I set up the idea of bistable illusion to acknowledge the fact that there are other points of view, since it’s clear that many sincerely believe we are on the path to growing convenience, security and progress, not least the creators of the video. But for me, the film depicts the hook-nosed hag, no question.

The video is the work of Thales, a global technology company which is developing a digital ID wallet that the European Union plans to make available to citizens of all member states. The EU has also launched a pilot programme to link the digital ID wallet to payments.

The EU bit is important. As I’ve highlighted in previous Substacks, the EU has been planning to introduce vaccine passports since 2018 and from my experience last winter, I now have a very clear picture of what vaccine passports mean for ordinary people. There’s my German friend, tearful and bemused during a two-and-a-half hour Skype, because she couldn't understand why she was banned from going anywhere except food stores. A mother in France put on a brave face, saying she didn't mind losing her job and there were plenty of other things to do apart from go to a library or cafe. A young Italian friend said it didn't matter if he had to have another unwanted injection because he didn't look after his health anyway. Over the past year I’ve heard countless people say, in sadness or resignation, that they got vaccinated in order to travel. And then there was me, sitting in the parks of Lisbon all winter because I wasn't going to show a QR code to have a meal or go to a co-working space.

So when the voiceover in the Thales video explains that the first service the ID app performs for Lucy, a psychology student, as she drinks her morning coffee, a chill runs through me. 'Right now, I'm reminding Lucy of the appointment she needs to schedule for her mandatory vaccination,' says the voice cheerfully. The government-issued app helps her throughout her day, verifying her identify for the exam she sits, reporting her passport lost and providing a 'smooth experience' in booking a rental car. It's central at her doctor's appointment (yes, her day does seem very medically-focused). And then, when she arrives at a bar to meet some friends it generates the QR code she needs to prove her age. 'So yes, I'm Lucy's best companion,' concludes the voice and Lucy's day ends as it began, with a fond look at the smartphone on her nightstand.

It’s not so much Big Brother as Constant Father. Lucy sees a few people as she goes about her day – the exam administrator, a doctor, the doorman at the bar – but every one of those interactions is mediated by the Thales app. Its authority and algorithms determine whether she has the right to have those interactions, replacing her formerly direct relationships with individuals and organisations. Her day is governed in minute detail by the state and a range of institutions and corporations, each with their own interests and visions of how things should work. Some of their requirements may be well-established and reasonable, others nakedly commercial and new regulations may be introduced with the best of intentions. But none of that matters. Decisions have been made by impersonal others. Lucy must scan.

This leads me to what I call the dehumanising aspect of the new techno-society. ‘Dehumanising’ may not be the right word; all this stuff is so new and overwhelming I hardly know how to describe it. But it captures something of how the Thales app and similar digital developments bypass the emotional and highly specific aspects of being human; the business of life in all its messiness. Are machines up to the job? Are the changes they bring about really what we want? And who or what is behind them?

This fictional film by James Graham for the Financial Times explores these questions in a brilliant, play-like format. (SPOILER ALERT: pause reading and watch it if you don’t want to know most of the plot.) In the wake of Covid, a young British woman has been called to a meeting. ‘How was lockdown?’ asks a man with a pleasant, professional manner. ‘Fine,’ she shrugs. She’s quite comfortable at this point; she's been signed up to take part in a study as part of her work. But as the conversation progresses, it becomes clear she’s under investigation for a breach of the lockdown rules. The man works for a data company which has been contracted by government to monitor citizens’ behaviour. They have lots of partnerships, he smiles, and the police often come to them for ‘intel’.

‘I no longer consent! This is beyond your remit. Your have no right!’ exclaims the heroine, a savvy barrister, as she realises the meeting is in fact an interrogation. But it’s too late. The software company, pulling together retrospective data from the woman’s mobile, smartwatch, home devices and footage from a neighbour’s Amazon doorbell, demonstrates conclusively that she broke the rules of the third British lockdown. Once the investigator’s notes have been uploaded into the system, the algorithm will issue its judgement.

The pair’s intense dialogue highlights our complicity, as modern people, with the developments that make this outcome possible. The images we so readily send to each other 'are being handed over to a tech company to store on a server that's probably in a different country with different laws, where it will sit, possibly forever,’ muses the interrogator. The young woman, an enthusiastic user of technology who voluntarily wears the smartwatch that helped give her away, has been colluding with the system that has trapped her. But the central philosophical issue is whether machines, programmed by distant governments, institutions and corporations, can know enough about human life to have this degree of control over us. People are individual, people are complex, protests the heroine. We don’t understand how algorithms work. In matters such as virus control, the data knows best, replies the other. ‘That’s why we must hand ourselves over to it. As emotional beings we are simply unable to measure that equivalence ourselves.’

No more spoilers. I’ll leave you to draw your own conclusion about what the film ultimately suggests.

IV

Until a very few years ago, I enjoyed going to the supermarket. The business of organising food had a comforting ordinariness, and in my local Sainsbury’s rows of cashiers chatted to the people they served. But increasingly I’m finding that British supermarkets inspire a strange mix of emotions that are hard to pin down: a sense of unease, mingled with a tinge of sadness and a bit of overwhelm. Getting access to the basics of life is becoming about dealing with machines, surveillance and security guards. Alongside sits the growing pressure to go digital, to pay in a way that enables other parties – the supermarkets, credit card providers and, at the flick of a legislative change, government agencies – to monitor what I’m buying and use that information for whatever purpose they sit fit.

This is the new world of food security that brings the complex mix of industrial and corporate forces Paul Kingsworth calls The Machine right into the acquisition of a pack of butter and a bag of carrots.

One day recently, walking disconsolately home from a local supermarket processing the mishmash of emotions elicited by The Food Machine, I saw this penny on the ground. It wasn’t shiny and portentous of luck, but battered and well, still there, so I picked it up. It seemed a sign of sorts.

The penny resonated with a mix of hopefulness and solidity that comes from pursuing an alternative path, the polar opposite of the life of Thales Girl, one involving both a return to the fundamentals of human life and a new way of living. And about the wisdom of that, I’m not remotely baffled.

The first steps along this path are modest and small-scale. For day-to-day purchases, I’ve gone cash-only. I cut up my loyalty cards a while ago and now shop less in supermarkets and consume simpler food easier to source elsewhere. I no longer buy from Amazon, although my books are still for sale there. (If you know of good alternative online booksellers please do share in the comments below.) I’ve largely de-googled and have ended a lifelong addition to the BBC. It’s surprising how easy it’s been to establish new habits and find alternative sources of sustenance.

I’m aware that I’m part of a trend of disconnection American author Greg Braden is witnessing in New Mexico. There, the artisans, farmers and creatives that make up his rural community have stopped voting, are taking their money out of the banks and are growing their own food. It’s their response to their loss of trust in the institutions they have depended on up until now.

‘It’s a catalyst for them to become more disconnected, more unplugged and revert to a way of life they’ve known in the past and that worked,’ says Braden. ‘The first reaction is to disconnect. And the response to that is to build something that meets the needs of the family and the community that is not tied into the systems that are no longer trustworthy. I’m seeing that big time.’

In Britain, new networks and groups have sprung up as part of this creative rejection of the mainstream. They range from informal gatherings in parks, pubs and community centres, born of the hunger of people to meet like-minded souls after the country’s long shutdown, to new organisations formed around specific goals of preserving freedom and wellbeing. Some, such as the soon-to-be-launched People’s Food and Farming Alliance, draw on deep-rooted concerns about the quality of our food, our relationship with our environment and the power of the supermarkets.

The trend is part of what Braden’s conversation partner John L. Peterson calls the path to the ‘new human’ in which people increasingly regard themselves as capable of meeting their needs without big institutions and technologies that are ‘all about control, and increasing control’. Instead, Braden predicts, old understandings about how to live will inform new technologies in ways that stay with people at the local level.

Change, he says, is ‘not going to come from the top-down. Islands of “new human” are emerging that I believe will converge into the larger society. And those that are not participating are then going to have a choice; they’re going to say “who’s happier? Who’s healthier? Who’s life is more fulfilled?” That’s the way it’s going to happen.’

On point thank you for these deep insights for a better way forward.

It’s interesting to see what giving up personal agency, over to the hands of Ai and algorithms, will eventually lead to. I get the argument for- that by the control of all our resources, via our behavior, we will be able to live sustainably off our planet. Notice the word off, because in this future we are truly not part of the earth and we are not from or with her and she is not our mother. We are in control of the earth, it’s resources, it’s inhabitants that we harvest for ourselves and we have rights over every being and every thing.

Unfortunately this is not something that can exist and has never existed and is in its fullest expression the wound of separation.

So yes it is up to anyone of us, who value our place In the dance of life to resist this movement, done in the name of our own good, ( sound familiar?) and to create culture and community where personal agency and responsibility to our physical place feels good. Where personal power is not gained by being over another but because of relationship with each other. Where we can feel. Feel human and feel what is mystery and what is greater than us.

I also had to stop listening to bbc radio four a couple years ago and am lucky enough to be able to have personal relationship with gamers and eat local. Commercial food i the USA, even the organic labels are rapidly becoming less and less tolerable to us as we deal with ongoing auto immune issues and chronic mystery Illnesses. And I’m grateful to my substack that allow me to stay informed but not bombarded. Thanks for this piece!