In this Bafflement Essay, I want to consider the failure to think.

‘I don’t want to think about it.’

It’s a phrase I’ve been hearing repeatedly during the Covid crisis, an indication that the speaker prefers to take things on trust and not concern herself with the dramatic changes sweeping life in the Western world.

A statement conveying attitude rather than propositional content, it’s often accompanied by the sibling ‘I’m not affected’. This second Covid-era statement, given as an explanation for why the speaker doesn’t mind the restrictions that others are complaining about, is also a way of shutting out consideration of the wider issues. It can be heard, too, in its absence, in the silence of those who seem to have lived these past two years without major disruption to their lives.

In normal times, such statements would be unremarkable, part and parcel of everyday conversation, a recognition of the truth that we can’t right every wrong, fight every battle. They can be understood as an acknowledgement that we have to live despite the fact there is much wrong with the world and that to be concerned with all its suffering and injustice would paralyse us. Turning away from misery is part of the human condition, a necessary part of self-protection, as Stanley Cohen pointed out in his pathbreaking States of Denial, a book that helped to debaffle me long ago in the wake of studying the holocaust.

But these are not ordinary times. Since the Great Forgetting that began in 2020, long-held values, basic rights and established ways of living have fallen by the wayside and, in places where they are now returning, are only being restored on a conditional basis. And yet it seems that many of those who grew up in the West don’t want to think about the implications of these changes, not for themselves, for wider society, or for the future. What can they be thinking? But I’m in danger of missing my own point. The bafflement which is the starting point for this essay lies in the failure to think.

To be fair, many people do recognise that profound and largely undesirable changes are taking place. But here enters a third, oft-heard attitudinal statement of the times: ‘I can’t do anything, anyway.’ In this case, the speaker recognises there is a problem but simultaneously excludes the possibility of meaningful action, thus absolving herself from the responsibility of taking a position. (1)

The attitude expressed by this third statement leads us to an aspect of the current crisis observed by political philosopher David Thunder, one of many experts banned from Twitter. (2) ‘There must have been an underlying problem in our culture because of the speed with which governments jumped on the bandwagon and adopted the policies of the Chinese Communist Party,’ he says in this episode of the Pandemic Podcast. ‘If our Western culture of freedom and constitutionalism was in good order I do not think we would have enacted any lockdown ... given that that happened, there must have been a rot in our culture already.’

The willingness of Western society to jettison its existing pandemic plans in favour of new, authoritarian measures reveals a lack of commitment to its key institutions and values, he goes on: ‘If citizens had a firm commitment to them I do not think they would have been so very receptive to dictatorial, highly coercive and intrusive policies to deal with a virus. So where does that leave us? What does the future hold?’

II

If previous times when the West forgot its culture of freedom are anything to go by, thinking matters.

One of the main questions for Hannah Arendt, a philosopher who lived through and then studied society-gone-wrong, is why, as her biographer Samantha Rose puts it, there was ‘a near universal breakdown of personal judgement in Europe’ under Nazism. ‘For Arendt, the question was: What is the difference between those who participated and those who chose to resist? The answer is thinking. Those who did not participate were the ones who dared to think for themselves, and they were capable of doing so not because they had a better system of values or because the old standards of right and wrong were still applicable, but because they asked themselves to what extent they would still be able to live in peace with themselves after having committed certain deeds... Those who did not ‘go along’ chose to think.’

Notice the phrase ‘dared to think’ (emphasis added). This is not thinking understood in terms of cognitive ability but thinking as a psychological disposition or, to put it in Arendtian terms, the capacity to deal with life as it is. ‘Comprehension, in short, means the unpremeditated, attentive facing up to, and resisting of, reality – whatever it may be,’ she writes in The Origins of Totalitarianism. Thinking in this sense is a kind of engagement with the world, one that enables the mind to see and ‘resist’ its dark side in favour of the spontaneous, creative response to life that Arendt sees as central to the human condition.

The historical examples reinforce the pertinence of the question: why do so many choose to ‘go along’ and not think?

In a lecture entitled ‘Thinking and Moral Considerations’, Arendt explores ‘the inner connection between the ability or inability to think and the problem of evil’ in greater depth. The lecture, given in 1971, was prompted by the ‘total absence of thinking’ that Arendt had observed in Adolf Eichmann when covering the trial of the leading Nazi – a baffling trait that she named ‘the banality of evil’. Nearly a decade later, in attempt to explain this controversial thesis further, she asked: ‘Is our ability to judge, to tell right from wrong … dependent upon our faculty of thought?’ she asks: ‘Do the inability to think and a disastrous failure of what we commonly call conscience coincide?’

When amplified on a social and political scale, she goes on, the problem with non-thinking is that it enables people to uncritically accept whatever rules are in force. And the more accustomed people are to following one set of rules, the more ready they will be to follow a new set, even if the new rules involve abandoning old values. ‘How easy,’ Arendt reflects, ‘it was for the totalitarian rulers to reverse the basic commandments of Western morality – “Thou shalt not kill” in the case of Hitler’s Germany, “Thou shalt not bear false testimony against thy neighbour” in the case of Stalin’s Russia.’

Easy because an absence of thinking is a natural state of affairs in human society. As an abstract activity which involves reflecting on absent objects, thinking interrupts doing, takes you out of the sensory world in which you, along with others, are rooted. It does not help you to survive or create new values; overall ‘it does society little good’, says Arendt, serving only to challenge and potentially destroy accepted ways of doing things. ‘Thinking,’ she concludes, ‘is a marginal affair in society. Except in emergencies’.

Except in emergencies. But we’ll come back to that.

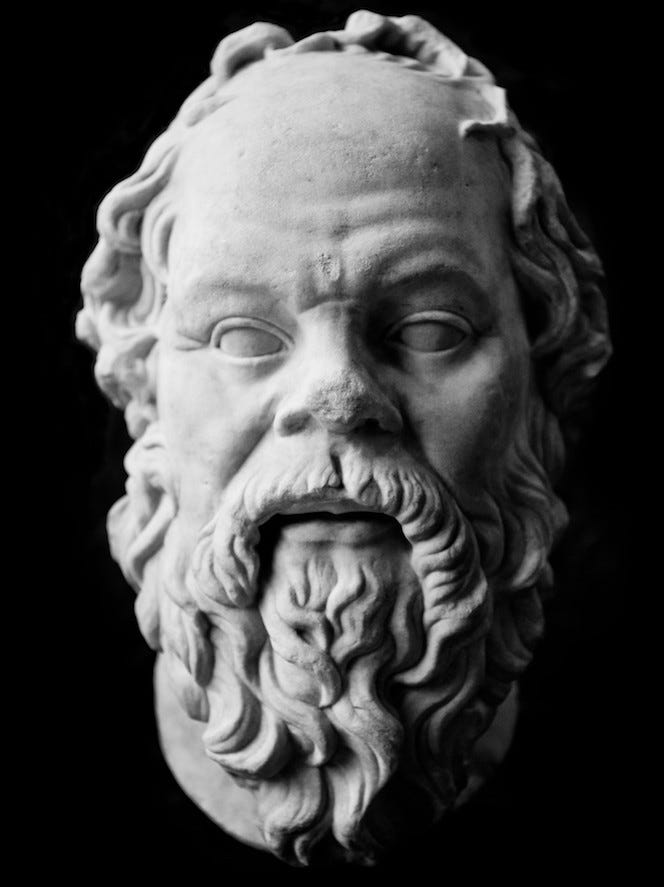

Arendt takes the arch-thinker of Western civilisation, Socrates, as an example of the social uselessness of thinking. The founder of the Western tradition philosophy was famous for teaching the young of Athens to engage in a form of reasoning which involved questioning accepted ideas and examining their assumptions. It achieved nothing except to disrupt the status quo. How irritating for his fellow citizens! Socrates, having been warned against this subversive activity, was eventually put to death for promoting immorality. The skill he taught of purging people of their unexamined opinions and ‘frozen thoughts’ was deemed to be ‘dangerous to all creeds’.

In the essay ‘Truth and Politics’, Arendt traces this hostility to thinking back to the old opposition of truth and politics. If the philosopher is interested in truth, the politician is interested in public opinion – and it seems that it was, at least in the Western world, ever thus. The philosopher and the state, the Socratic impulse to question and disrupt and the social drive to maintain consensus and rule-following, are pursuing different interests. While the Platonic philosopher goes in search of eternal truths from which principles can be derived, politicians and citizens are content to organise life around ‘ever-changing opinions’. In the Greek polis, the model for Western democracy developed as a domain of persuasion in which the facts change. And usually that doesn’t matter too much: the citizens accept and forget the lies of the politicians and life goes on, in all its sensory absorption and endless doing.

Until, that is, the politicians get out of hand and the lying becomes systemic. At that point, Arendt says, the truth teller comes into his own, deploying the disruptive capacity of questioning to initiate change: ‘Where everybody lies about everything of importance, the truth teller, whether he knows it or not, has begun to act; he too, has engaged himself in political business, for, in the unlikely event that he survives, he has made a start toward changing the world.’

‘In the unlikely event he survives.’ For the citizenry is unlikely to recognise that thinking has suddenly become socially and morally useful and be grateful for such truth-based interventions. Those approaching politics from the perspective of truth tend to be the outsiders within: Arendt invokes ‘the solitude of the philosopher, the isolation of the scientist and the artist, the impartiality of the historian and the judge, and the independence of the fact-finder, the witness and the reporter’. The diverse list is unified by a common feature: none on it has allegiance to a cause or a tribe. And that means that ‘politically relevant functions are performed outside the political realm. They require non-commitment and impartiality, freedom from self-interest in thought and judgement.’

In times of trouble, what Arendt calls the ‘Homeric impartiality’ which is uniquely characteristic of Western civilisation, comes into its own: ‘When everybody is swept away unthinkingly by what everybody else does and believes in, those who think are drawn out of hiding because their refusal to join is conspicuous and thereby becomes a kind of action.’ The ‘wind of thinking’ pioneered by Socrates becomes a liberating force, able to awaken conscience and the capacity to make moral judgements.

III

To recall an earlier point, the capacity to engage in this kind of thinking seems to be largely a matter of psychology and temperament. So, if the ability to think is a matter of psychology and if, in difficult times, thinking – now understood as a form of action – is linked to daring, perhaps there’s a need for more psychological understanding in politics.

But what if modern psychology is part of the problem?

The American psychologist James Hillman, in conversation with the writer Michael Ventura, argues that it is. In We've Had a Hundred Years of Psychotherapy – a kind of ‘thinking-as-dialogue’, as Hillman describes the format – the pair discuss why there is so much passivity in late twentieth century America.

‘There is a decline in political sense,’ says Hillman. ‘No sensitivity to the real issues. Why are the intelligent people—at least among the white middle class—so passive now? Why? Because the sensitive, intelligent people are in therapy!’

Psychotherapy – Hillman’s work as a Jungian therapist for decades – only deals with the ‘inside’ soul and, in so doing, removes the patient’s attention from what’s wrong with the outer world, he explains. Even when the client brings what is clearly a political problem into the consulting room, the therapist treats it as stemming from his childhood or as an expression of a personal complex. In helping him to cope with a dysfunctional world, the modern therapist fosters the development of the child archetype, an apolitical, disempowered human who is disconnected from the society in which he lives.

‘By removing the soul from the world and not recognizing that the soul is also in the world, psychotherapy can’t do its job any more. The buildings are sick, the institutions are sick, the banking system’s sick, the schools, the streets—the sickness is out there … therapy, in its crazy way, by emphasising the inner soul and ignoring the outer soul, supports the decline of the actual world.’

The cure, as far as the practice of psychotherapy goes, would for the consulting room to be re-politicised, to become ‘a cell of revolution’: ‘By revolution I mean turning over. Not development or unfolding, but turning over the system that has made you go to analysis to begin with—the system being government by minority and conspiracy, official secrets, national security, corporate power … Revolution ‘begins with the realization that things are not right and an analysis of how they are not right … And instead of imagining that I am dysfunctional, my family is dysfunctional, you realize what R. D. Laing said long ago and Freud, of course, too: it is the civilization that is dysfunctional. The society is dysfunctional. The political process is dysfunctional … The therapeutic task [is] not to tell a person how to fight or where to fight, but the awareness of dysfunction in society, in the outer world.’

Is this what Western society needs? To develop a psychological perspective that is outward-looking, taking the awareness of dysfunction in the individual self and helping the patient to return to the world with a resolve to change it?

IV

How might these insights into thinking apply to the current situation?

Perhaps the first point to make is that the failure to think has taken place precisely among the social groups we usually associate with thinking: the educated. As Mattias Desmet has pointed out, when societies become consumed by a single narrative coming from Authority, it is often the most educated who are in the vanguard. It’s notable that in the Covid crisis, at a public level, the calls for restrictions have come largely from the middle classes and the institutions that represent them, with others in that demographic well-placed, in comfortable homes with work that can be done remotely, to go along with them.

In Canada, Dr David Haskell and Dr Julie Ponesse wonder how one of the most famously liberal countries in the world has undergone a profound, top-down reversal of values with almost no questioning from the citizenry. ‘We give most people too much credit in terms of them actually thinking through what is happening in their own life, the narratives they’re being sold,’ says Haskell. He cites sociological evidence showing how this trait means that a passionate minority of ten to twenty per cent can succeed in imposing their views on society. ‘Eighty per cent of the population will go along with it. And so we see, sadly, that most people don’t really engage with the facts – beyond the immediate needs of their family, they don’t look at the larger culture and they don’t ask why.’

Such reflections chime with my own observation of how eager many in Britain have been to follow new and extraordinarily constraining rules down to the last detail. In 2020, I listened to radio phone-ins in which caller after caller rang to ask for advice, baffled at the relish of a newly-appointed expert at telling others what they could and couldn’t do, and the audible relief of the caller at receiving detailed instructions. Joining a circle of people in the park for an outdoor meeting, I saw first-hand how much panic could be induced by not following the rules to the letter. ‘Now we are seven!’ shouted the organiser in alarm. ‘We are only meant to be six. We must comply!’ (3)

In a television discussion in late 2021, historian and broadcaster Neil Oliver suggests that the underlying reason for such compliance has to do with freedom and personal responsibility being experienced as a burden. The willingness of the population to have the smallest details of their lives directed from above created a new dynamic. After the first lockdown, ‘the government latched onto the fact that a lot of people quietly quite like just being told what to do’, he observes, and that made the continuing imposition of restrictions easy.

His partner-in-conversation, commentator Emma Webb, agrees: ‘In many ways we’re living in a very immature society … Many of the younger generation are quite immature and do enjoy being nannied by the state.’ The Covid crisis has seen a worrying shift in the understanding of the relationship between the individual and the state, she goes on, one that sees freedom as something granted by the state as a reward for good behaviour, treating the citizen ‘as you would a child’. The arrival of the vaccines has brought a second major shift – again undiscussed and unthought-through – to the idea that the body of the individual falls under the jurisdiction of the state and the majority.

It seems that a similar sea-change has taken place in the United States, illustrating Hillman’s description of an individualised, apoliticised society. This winter I’ve been doing an online course in which the teacher and most of the participants are American. I don’t want to identify it, so let’s just say the course encompasses issues of social and historical injustice in a culture of openness and authenticity. Given its contents, I was baffled to find that, week after week, the online seminars made no reference to the life-changing conditions under which many are now living. Surely, if such constraints continue, they will prevent course participants from realising even the more modest aspirations, never mind the juster world being envisioned? Taking a deep breath, I pointed to the elephant on the Zoom call. But the question drew a blank and I was told that the course dealt only with ‘personal values’.

V

At the end of their discussion, Hillman and Ventura come to a stark conclusion.

‘A great culture, Western culture, is dying. Or, to put it a little less darkly, it’s transforming such that you won’t be able to call it Western civilization any more,’ says Ventura. ‘Nobody knows what’s going to come. The New Agers think a marvellous period is about to dawn; the right and left each live in fear of the other “winning” the transformation; while the technocrats think they’re going to reprogram humanity. In reality, it’s out of everyone’s control, and the very grasping to control it just increases the momentum and cost of the decline.’

Doesn’t that sound familiar? The prescience of the conversation is remarkable, as the pair evoke environmental destruction, social atomisation and the raising of children on junk food and mass entertainment. But Hillman and Ventura were talking thirty years ago, when the internet was in its infancy. At points their dialogue is interrupted by calls from people close to them, and the thinkers reflect on how modern modes of communication express the separation of people living in a fragmented society. But – how quaint – the calls are taken by an answer machine!

What all this suggests, following the thinking of modernity’s discontents such as Paul Kingsnorth and Charles Eisenstein, is that the roots of the Western world’s extraordinary response to a new but foreseeable respiratory infection go back decades, even centuries, and lie in the forces that shape the modern world. Kingsnorth uses the phrase ‘the Machine’, Eisenstein the Story of Separation to denote the cluster of disconnections and dysfunctions arising out of the way we live now – disconnection from the land and the seasons, from the sources of our food and the breakdown of communities and relationships, all wrapped up in a general loss of meaning and the growth of consumerism.

On this view, what we are seeing play out in the Age of Covid is the natural expression of trends that extend far wider and deeper than public health. The modern state is revealing, alongside the many virtues of the enlightened form of government which replaced the feudal and monarchial systems, a dark side in which it joins forces with commercial agendas and digital technology to create a new kind of controlling power. The previous tyrannies of modernity were based on visions of an ideal, perfectible state, whether nationalistic (Nazism), universal (Communism) or a hybrid of both (Albania). In the early twenty-first century, the cushioned life of the West has paved the way for the emergence of a new version of political perfectionism – a Safe Society governed by an elite of experts applying the truths of Science. In such a society, there’s not much need for thinking – in fact, thinking can be counter-safety. What is required is mass compliance with the rules of disease-prevention.

I don’t know how seriously to take predictions of the end of Western civilisation – an increasingly common view among thinkers of different stripes – but it seems clear that, at the very least, Western society has arrived at a very serious fork in the road. In early 2022, it looks as though the pandemic is ending. ‘It’s over, people,’ declares Alex Berenson, the American science journalist who has relentlessly scrutinised the real-world evidence on the progress of both Covid and its vaccines. Eugyppius agrees that ‘it’s the beginning of the end’ for the disease but wonders whether ‘Corona has swept away the last vestiges of liberal democracy in Europe, and perhaps in the whole world.’

Over the past two years, many moral and political lines have been crossed, and things unthinkable prior to 2020 have been accepted with little or no public debate. If you’re reading this in a green and pleasant land, there is cause for rejoicing. But over continental Europe the skies are dark. At the time of writing, Austria is about to introduce mandatory vaccination on pain of ruinous fines, while Greece is already levying monthly fines on ‘the unvaccinated’. Meanwhile in France President Macron has dubbed those who have not had Covid jabs ‘non-citizens’ and vowed to harass them ‘to the end’. The country seems to be moving towards, as Josie Appleston puts it, ‘a new QR-code citizenship based on regular compliance with medical procedures’.

In recent weeks, I’ve been hearing a lot about the daily lives of the newly-created minority of ‘the unvaccinated’. A friend in Berlin can no longer go anywhere except the supermarket and the pharmacist, although this doesn’t bother her as much as the prospect of losing the job she loves in social care. A young woman describes how she can no longer work, go to the library or take part in French cafe culture. Instead, she hosts dinners at home. They are going so well that her vaccinated friends ask if they can come too, and she graciously invites them. In Lisbon last week, I popped into a local fast food chain to satisfy a craving for a burger. When the young woman behind the counter asked for my Covid certificate, I told her I didn’t have a phone on me – I use a dumbphone which I often leave at home. She was astounded. As was I – I still can’t believe that we are training a new generation that you need to carry a digital device to demonstrate you have state permission to buy food, permission which can be deactivated by faceless bureaucrats. (I got my burger elsewhere, just in case you’re wondering.) Old Europe, the centre of the democratic, civilised world, is becoming a very strange place. Many people I know are considering packing up and leaving.

Meanwhile, pan and non-governmental organisations are keen to use what Klaus Schwab has called ‘the window of opportunity’ opened by Covid to introduce some long-planned changes. The European Union (which, it turns out, has been planning an EU vaccine certificate since 2018) has published plans for a travel framework which would disbar ‘the unvaccinated’ from non-essential travel. Passports will have to be updated every nine months with boosters manufactured by EU-approved brands. (4) The World Health Organisation is in the process of negotiating a new, legally-binding accord which would oblige governments to implement its recommendations for future pandemics. The new treaty, primarily led by the EU, could give the WHO the power to impose the kinds of measures pioneered over the past two years on countries around the world.

And riddle me this: Tony Blair – he who’s back on the scene pushing for vaccine passports following a failed aspiration to introduce ID cards while British Prime Minister – is on record as saying his teams are ‘embedded in governments around the world’. What can he mean?

Do we in the West really want such a highly-regulated way of life? Is the ‘collective good’ to be defined by a mix of state, commerce and (a particular approach to) science? Do we want the measures of the past two years to become the template for future crises? Are we happy about ending the principle of informed consent that is the bedrock of Western medicine?

Living without thinking is a fine and natural thing. Except, that is, in emergencies.

It’s time to do some proper thinking about the ‘health society’ that has come into being over the past couple of years. And that will be the subject of the next Bafflement Essay.

*

Notes

1. I’m put in mind of the story of the three fish, as told by Michael Meade. Three fish are swimming around in the river when a fisherman’s net appears over them. One fish, recognising it for what it is, immediately swims away, upstream. The second fish swims backwards and forwards for a while, wondering what the best course of action would be. The third fish, not understanding the significance of the net, ends up in the frying pan.

2. The interview with David Thunder includes a discussion of how censorship by big social media platforms such as Twitter, Facebook and YouTube means that private companies are increasingly controlling debate in the public sphere. My own recent suspension by Twitter for the use of a metaphor is a case in point. The company ruled that the expression ‘hitting yourself on the head’ amounted to promoting suicide and self-harm.

3. Ah, the Rule of Six. I don’t have the bureaucratic energy to explain, but if you’re unfamiliar with it, details are here.

4. The press release detailing these plans has now disappeared from the europa.eu page on which it was published.

Attentive subscribers will note that I am not writing the lyrical pieces about Lisbon that I promised. This is partly because there are currently more urgent things to write about and partly because life in Europe, while it still has its beauty, is becoming increasingly difficult. But please know that in time I plan to vary the long, research-intensive Bafflement Essays with shorter pieces on a wider range of themes, including place.

Really good and to the point.

Fantastic essay Alex. Really appreciate it.

I can't tell you how many people have disappointed me in the last 2 years.

I often wonder how they get dressed in the morning.

Mostly the more degrees the person has, the shallower the thinking.

Sleepwalking out of our civilization. Sometimes hopping and skipping and bouncing.

Sickening.