The hidden mechanisms of unfreedom: part IV

Circumventing democracy - and the health data grab

This Substack attempts to get to the heart of the matter and examine what the mechanisms of unfreedom are all about.

Along the way, it brings together a host of information about how our health data is being transferred, via the NHS, to a wide range of organisations who plan to use it in a variety of ways. It's impossible to overstate the significance of this handover of our medical data: it's the kind of thing after which people tend to ask, when the consequences have become horribly clear: “how did this happen?”

Well, much of the answer is available right now in what follows.

The quiet transfer of the medical information of an entire population without public debate or parliamentary scrutiny is a prime example of how democratic processes and safeguards are being bypassed. Circumventing democracy is key to the success of a project which, its proponents hope, will transform modern democracy into a new form of governance according a powerful minority near-absolute power.

Describing this new form of political power, hampered as we are by the perceptions of old paradigms, is tricky. Some people call it “communist”, but its reach extends way beyond centralised state control. Since its processes are driven by the wealth of corporations and billionaires, it's tempting to call it “capitalist”. But while capitalism may be keen to exploit, it's not particularly interested in control. “Fascism” fails to capture the global aspect of the new tyranny and ignores the importance of technology. “Authoritarian state capitalism ideally on a global scale”? Close, but a bit wordy.

I'm going to call it global technocracy.

It's helpful to start by looking at the issue from the technocrat's point of view. In the mind of someone who i) knows best ii) can see how technology can realise their vision for the world and iii) has the resources – personal drive, contacts, money – to get things done, democracy is a problem. By its nature, democracy relies on the consent of the very people who don't know what's best and has safeguards against autocracy. Our technocrat realises that it will cause a big fuss if he attempts to impose technocratic rule in an obvious way. So he works out some strategies to get round the obstacles of the democratic system: mechanisms which appear to be about improving or saving democracy but actually transfer power from the people to technocratic institutions. It's done so quietly and incrementally that few will notice and, by the time the new order's in place, it's too late to do much about it.

The mechanisms of unfreedom tend to overlap: citizens' assemblies, covered in the second piece in this series, are one way of creating the impression of a quasi-democratic mandate for restrictions and taxes that few people want. Such forums take place in plain sight and make use of both manipulation and publicity. But unless you're a policy nerd and pay attention to the “who” and “how” of things, a more significant way of circumventing democracy is less easy to spot. Seeing it requires looking away from the main action on the stage to notice the minor character lurking in the wings.

Enough of the drama metaphor! I'm talking about the extraordinary levels of influence being exerted on Western governments by organisations who have no interest in democracy and clearly believe that the messy variety of human existence needs to be moulded into a homogeneous unit to be more easily managed by them.

This is the infiltrate-and-influence approach exemplified most famously by the World Economic Forum and Klaus Schwab's boast that WEF people “penetrate the cabinets” of the world's governments. Such penetrators have acquired the values and skills to influence national policymaking on training programmes. The WEF's three-year Young Global Leaders programme has alumni from 120 countries; UK-founded Common Purpose has 125 alumni. Like degrees at Oxbridge and other elite education institutions, these courses result in contacts and alliances to be used in future careers.

The WEF Young Global Leaders Foundation was set up in 2004 and Common Purpose started out as a charity in 1989. Until 2020, I would have dismissed such organisations as business networks that had little or no bearing on my life. But Technocracy takes time, and only recently have we begun to see the results of these networks.

In this insightful review of Tony Blair's On Leadership (a kind of Machiavellian manual for technocrats), Nathan Pinkoski pinpoints the conception of leadership which underpins technocracy, that of leader as “CEO-king”. In this form of governance, policy doesn't come from the ground up, the will of the people carefully crafted by elected representatives and impartial civil servants into legislation in what’s sometimes called the social contract. It’s created at the top: “Blair argues that successful leaders are those who devise the policy first, then do politics—not the other way around. “The politics”—the retail of selling it to the people—is “layered on top once the answer is decided.”

It's a model which is inherently hierarchical. For Blair, “power flows not from persuading equals, but from establishing superiority through expertise, then commanding others to act and having them obey”. The question of what legitimises this power, how it's decided who becomes leader, is never addressed. Perhaps that's part of the point: the ruling technocrat does not need to justify his position to mere plebeians: his power just IS.

Now we are closer to understanding why democratic processes pose such a problem for the technocrat – and why he needs to change or bypass them without appearing to do so. Hence the strange language and inverted reasoning we often hear from supra-national bodies and think tanks: censorship is needed to “save democracy” and Western governments must be “reimagined” so as to work more effectively with corporate interests and Big Tech.

Technocrats Make Policy

In the first piece in this series, I described how some UK think tanks have become arms-length bodies for state policymaking. I characterised this as a kind of hijacking because established think tanks didn't set out to do this: their stated purpose is to be independent civil society organisations which serve the public good.

But the think tanks described below were set up with the explicit intention of influencing government and taking Britain in a new, technocratic direction. The biggest, The Tony Blair Institute for Global Change, could be considered the UK's very own, homegrown WEF.

Established by Blair in 2016, the TBI is a not-for-profit organisation which is technically a company. It has 900 staff in over forty countries, described on its website as “a global team of political strategists, policy experts, delivery practitioners, technology specialists … from the public, private and tech sectors”. While classical think tanks focus on research, the TBI's purpose is explicitly about influence: “We help governments and leaders get things done. We do it by advising on strategy, policy and delivery, unlocking the power of technology across all three.”

The TBI has grown rapidly in a short period of time. Its website gives no information about how its funded, but details of some of its main funders have emerged from various official sources. They include the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the Larry Ellison Foundation, the UK Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office and the US Agency for International Development.

So far, so typical of the alliances between the public, private and tech sectors that characterise emerging technocracies.

The TBI has served as a platform for Blair's repeated calls for compulsory national ID, a policy he tried and failed to introduce when officially in power 1997-2007. Since then, Blair has repeatedly called for digital ID on a variety of grounds, calls which have intensified since Labour got into power.

In an article published in The Daily Mail and on the TBI website in January 2025, Blair argues that digital ID will solve a multitude of problems for government: “A digital ID could significantly improve the way that citizens interact with government – saving them time, easing access and creating a more personalised service.”

For citizens, he uses the seductive appeal of convenience: “Imagine that all your health information was in one place: easy, with your permission, for anyone anywhere in the health service to see. That your passport, driving licence, anything you need to prove your identity, were in one simple digital wallet, unique to you. That you could purchase and pay for any goods or services using your digital ID”.

Blair knows the nation doesn't want digital ID. At a conference hosted by the TBI in July 2024, he admitted with something of a snigger that there was “a little work to do in persuading” us. But this is not about what British people want; this is about the kind of world the technocrats want to create.

Despite assurances that it would not make digital ID compulsory, in June it emerged that the government is considering compulsory digital ID. The news was indirectly announced in comments from environment minister Steve Reed in a radio interview about the proposals for a “BritCard” by the think tank Labour Together.

Like Blair's institute, Labour Together is a newish think tank set up with an explicitly political purpose. It was founded in 2015 by a group of Labour MPs which included Reed, Rachel Reeves and Wes Streeting, describing itself as “a think tank putting forward a new vision for Britain under a Keir Starmer administration”. The Labour Together website doesn't give details of its funders, but this article reveals that the organisation has only ever been supported by a small number of wealthy individuals. Labour Together is headed by former MP Jonathan Ashworth – you remember him, he was that nice shadow health minister who kept pushing for longer, harsher Covid restrictions.

The reasoning, as I wrote in this piece for The Spectator, in Labour Together's BritCard report is shamelessly bad. Citizens must accept compulsory digital ID because: “This is your country. You have a right to be here. This will make your life easier. It is at the heart of the social contract.”

But the art of political persuasion doesn't require good public reasoning. Labour Together use the classic unfreedom mechanism of manufacturing consent to create the impression that digital ID is inevitable. In a poll, 1912 respondents were asked to what extent they would support a digital ID if used by employers, landlords and public officials to check whether people were in the country legally and entitled to services.

Initially, the tactic of presenting digital ID as a solution to a problem about which there's a lot of public concern seemed to work: 80% of respondents said they would support such checks. But when presented a list of “most significant benefits” of digital ID, only 29% thought it might deter people from coming to the UK or accessing public services illegally. The question about “concerns” got the clearest response of the whole poll: 40% thought digital ID could be misused by the government, with 23% thinking it would increase the black economy.

Why so much effort to introduce something that's not wanted and clearly won't fulfil its stated purpose? The first, and most obvious answer is “control”. Digital technology makes the level of surveillance depicted in Nineteen Eighty-Four a realisable aspiration. As the documentary The Agenda lays out with great clarity, digital systems, whether for travel, health certification or identification purposes, can be readily used to limit our access to the resources and activities we need to live, to make them conditional on compliance. These are not hypothetical dangers: all the necessary systems are now being set up and – one good thing about technocrats – if you listen, they'll tell you their plans quite clearly.

Look further behind the scenes and one particular reason why the technocrats are intent on imposing digital ID comes into view.

Our medical information.

The Future of Britain section of the TBI website introduces a series of detailed policy proposals with the claim that technology, notably AI, is central to the “reimagined state”, the political entity that will somehow save us from disaster. In healthcare, interlocking reports outline the systems and infrastructure needed to realise “the immense potential of the UK's health-data assets”.

They also involve legislative changes to overturn the model in which medical information belongs to the individual concerned and state agencies become the “data owner”. In other words, the medical information of the British population is to be monetised and made available to the pharmaceutical industry and biotech sector to help them develop new products which they will then sell back to us.

“Health-data assets” is a phrase which comes up a lot. It signals the recognition by those with power that the information held by the NHS – detailed health records for an entire population covering every age, ethnicity and condition – are the best population health data in the world. It’s an extremely valuable data set, a fact not lost on health secretary Wes Streeting who in opposition remarked that the NHS had “struck gold”.

Let's take a look at the building blocks of the system proposed by the TBI:

May 2024: A New National Purpose: Harnessing Data for Health proposes the creation of a new company owned by the government and the NHS with investment from industry. Operating as “a professional commercial entity”, the organisation would act as a broker for our health data, generating an estimated £250 million in annual revenue and billions more from “wider benefits”.

August 2024: Preparing the NHS for the AI Era: A Digital Health Record for Every Citizen argues that the government should create “a digital health record” that would become “the single source of truth for every citizen’s personal health data”. Hosted on cloud infrastructure and updated by information from wearable health tech, the digital health record would enable multiple parties, including commercial and research companies, to access patient records.

December 2023: Moving from Cure to Prevention Could Save the NHS Billions: A Plan to Protect Britain outlines a preventative health programme to “sit alongside the NHS”. The digital health record would form the basis for an AI-generated a personal health risk profile for each citizen which in turn could lead to the prescription of “new prevention drugs”. Accordingly, preventative vaccines need to be developed and made widely available at speed: “spurred by the Covid-19 pandemic, there are more vaccines in the pipeline than ever before and now is the time to prepare the UK’s health system to absorb a new age of innovations that are proved to be safe and effective”.

And there you have it: a system whereby the population is continuously surveilled, with citizens undergoing health screening and remote monitoring in order to be prescribed new treatments by the state and its commercial partners. It’s a great business plan.

A fourth report completes the picture.

May 2025, A New National Purpose: Biosecurity as the Foundation for Growth and Global Leadership by Tony Blair and William Hague outlines the elements of a national disease surveillance programme involving AI-driven infection detection and real-time biometric data gathered from devices worn by citizens.

Government departments should be reorganised, the former politicians argue, to create “a centralised approach to biosecurity” with a task force of “biotech-industry specialists” ensuring that biosecurity threats are a priority. A “tiered biosecurity-response plan … with clear intervention thresholds would trigger action, allowing government to cut through “bureaucratic inertia” and “speed up early decision-making” in response to suspected disease outbreaks.

Imagine the potential to mandate quarantines, closures and medical interventions at speed: the kinds of measures proposed by the World Health Organisation in its Pandemic Treaty, amended International Health Regulations and new public health legislation in Northern Ireland.

We had a foretaste of what happens when a link between medical information and the ability to access venues and services was made, for the first time in human history, during Covid. The NHS app was created as a means for admin such as book appointments but it wasn’t long before its developer recommended it be used as an “immunity passport”. Blair was a leading voice in the UK push for vaccine passports, arguing they were the way out of lockdown. It's no coincidence that the lead author of Less Risk More Freedom published by the TBI in 2019 Kirsty Innes also wrote Labour Together’s BritCard report.

Back then, you could reject the Covid Pass by simply not downloading the NHS app. In Portugal, where Covid passports became a condition of entry to most places, I refused to share my medical information with a man serving coffee and walked away.

But with mandatory digital ID, our health data becomes part of the state apparatus, easily viewable, as Blair puts it, by “anyone anywhere” and linked to other government departments and services. Once in place, government would naturally use it to achieve its aims: there’s already a suggestion in the BritCard report that legislation would be changed to make digital ID a condition of employment.

Before we rush to conclude that the TBI has been using its considerable resources including the expertise of a former prime minister to circumvent British democracy, let's take a look at how far down this path the government has already taken us.

In 2020, while we were confined to our homes, some people were busy behind the scenes establishing the infrastructure to maximise the benefits of our health data.

The US tech firm Palantir began its association with the NHS in March 2020 when it was hired to gather information from medical tests and 111 calls to help plan the Covid response.

Previously, Palantir had contracts with the Pentagon, Israeli military and the Ministry of Defence and been embroiled in controversies for using software to facilitate mass deportations and eliminate prospective employees on racial grounds. You or I might think that a background in surveillance, discrimination and military operations might not be the best qualifications for dealing with personal health information. But three years later, Palantir was given a seven-year, £330 million contract with NHS England to build a federated data platform bringing together the medical information held by NHS trusts and social care providers. The contract was heavily redacted, with 416 of 586 pages blacked out, and a subsequent legal challenge from The Good Law Project revealed that parts were still being negotiated – including a section on the protection of personal data – even after the deal was signed.

So far, so bad. But at least concerns about data privacy have meant that only around 100 of the 240 NHS trusts in England have handed over patient data to the Palantir platform. They seem a bit more savvy than Andrew Marr who, writing in The New Statesman, sweetly suggests we should have “assurances” from Palantir about how it plans to use our information.

In November 2020, during the second national lockdown, the Centre for Improving Data Collaboration was set up to “realise the value of health data assets” and build capacity for “negotiations”. The word “sell” is not mentioned but the language is strikingly commercial.

Then, in 2021, while people were reeling from the consequences of the Covid restrictions, it emerged that patient data was being transferred from GP surgeries to a national database. There was a brief window during which you could opt out but if you missed it, information about your physical, mental and sexual health going back ten years, including details of gender, ethnicity and sexual orientation, were automatically transferred to NHS Digital in England. With concerns about data privacy, there were calls for a delay, but NHS Digital responded with a version of the Covid mantra: “Patient data saves lives”.

NHS Digital wasted no time in sharing some of my data. Returning from Portugal in 2023, I found a letter dated November 2022 from an organisation I'd never heard of inviting me to take part in medical research. As part of “the UK's largest ever health research programme”, Our Future Health wanted me to give them full access to my medical records, answer some questions and provide a blood sample. In return, I would get a £10 voucher to spend in a supermarket or chain store. Looking at their website, I found that all this information could potentially be shared with their commercial partners around the world who include AstraZeneca, Pfizer and Regeneron Genetics Center.

As I described in a previous Substack, it took me two goes to opt out of NHS Digital to ensure this doesn't happen again.

In July, the Labour government published details of its flagship policy for NHS reform. Fit for the future: 10 Year Plan For England (which sets the template for healthcare in the devolved administrations) outlines “three radical shifts” to create a “reimagined NHS”: moving healthcare from hospitals to the community, a new emphasis on prevention and digitalising the NHS. The Plan has been covered extensively by the mainstream media but the responses have mostly focused on whether these aspirations are realistic, whether they will improve patient access to care and whether the right kind of workforce exists.

This betrays a huge blindspot about what The Plan aims to accomplish.

A first clue as to what lies behind that blindspot: The Association for the British Pharmaceutical Industry likes the proposals but wants a greater proportion of the NHS budget spent on innovative medicines and vaccines.

The real giveaway is The Plan’s predominant focus on new technology. There's little or nothing about the human aspect of healthcare or the root causes of ill-health; instead the priority is to develop “5 transformative technologies: data, AI, genomics, wearables and robotics”. Note what is both obvious and unsaid here: all these areas are expensive, experimental and necessitate strong partnerships with Big Tech, the biotech sector and the pharmaceutical industry.

Let’s look first at data. A Single Patient Record is to hold the medical record of every member of the population, with legislation passed to remove data protection regulations and allow patient information to be shared across the NHS and with third parties. We, the citizens, will access our record via the NHS app, set to become “the digital front door to the NHS” and the (only?) means by which people will be able to make same-day GP appointments.

The Plan is big on wearables. Smart watches and smart rings are to become “standard in preventative, chronic and post-acute NHS treatment”, monitoring those suffering from heart disease, diabetes and cancer. As our “personal health custodians”, wearables will give us “personalised nudges for healthier behaviours” and alert professionals about our current state.

Citizens are to be “incentivised” to make healthier choices through a new reward scheme. The Plan doesn't give details of this, but it does feature a case study of a Singapore scheme whereby citizens “earn health points by engaging in activities such as walking, purchasing healthier food options, and participating in health screenings. These points can be redeemed for e-vouchers usable at places including supermarkets and restaurants”.

Wearables will feed information into the Single Patient Record, providing the real-time data needed to prompt interventions by health professionals. So it's not surprising that even greater monitoring of citizens' health is envisaged through the use of technology at home and work:

“As well as wearables, we expect an expansion in the use of biosensors in the home, and even the workplace, providing a more constant flow of information. We will see miniature, highly accurate biosensors continuously monitor a wide array of physiological parameters (glucose, electrocardiogram, blood pressure, stress, complex biomarkers). Health monitoring will happen via smart fabrics and nanotechnology will enhance sensor capabilities.”

All this is in service of a grand ambition: to “turn the NHS into a prevention service” and make “the proactive management of patients ... the new normal”. Generative AI will create personalised care plans while vaccines, including innovative products for conditions not historically treated by vaccination, will be used more widely: “mRNA technologies – used in COVID-19 vaccines – are showing huge potential. There is particular promise in cancer immunotherapy, where personalised cancer vaccines can be designed to recognise and eliminate cancer cells”. Clinical trials are to be expanded, with the NHS app encouraging millions to sign up as participants. The app will “enable all of us as citizens to play our part in developing the medicines of the future. The British people showed they were willing to be part of finding the vaccine for Covid, so why not do it again to cure cancer and dementia?”

The image of the human genome on the cover of The Plan signals an even greater ambition: to create “a new genomics population health service by the end of the decade”. The first stage it to a study to sequence the genomes of 150,000 adults. Later, the universal (=mandatory) genomic sequencing of newborn babies will provide the information to identify disease risks and prescribe treatments on a preventative basis.

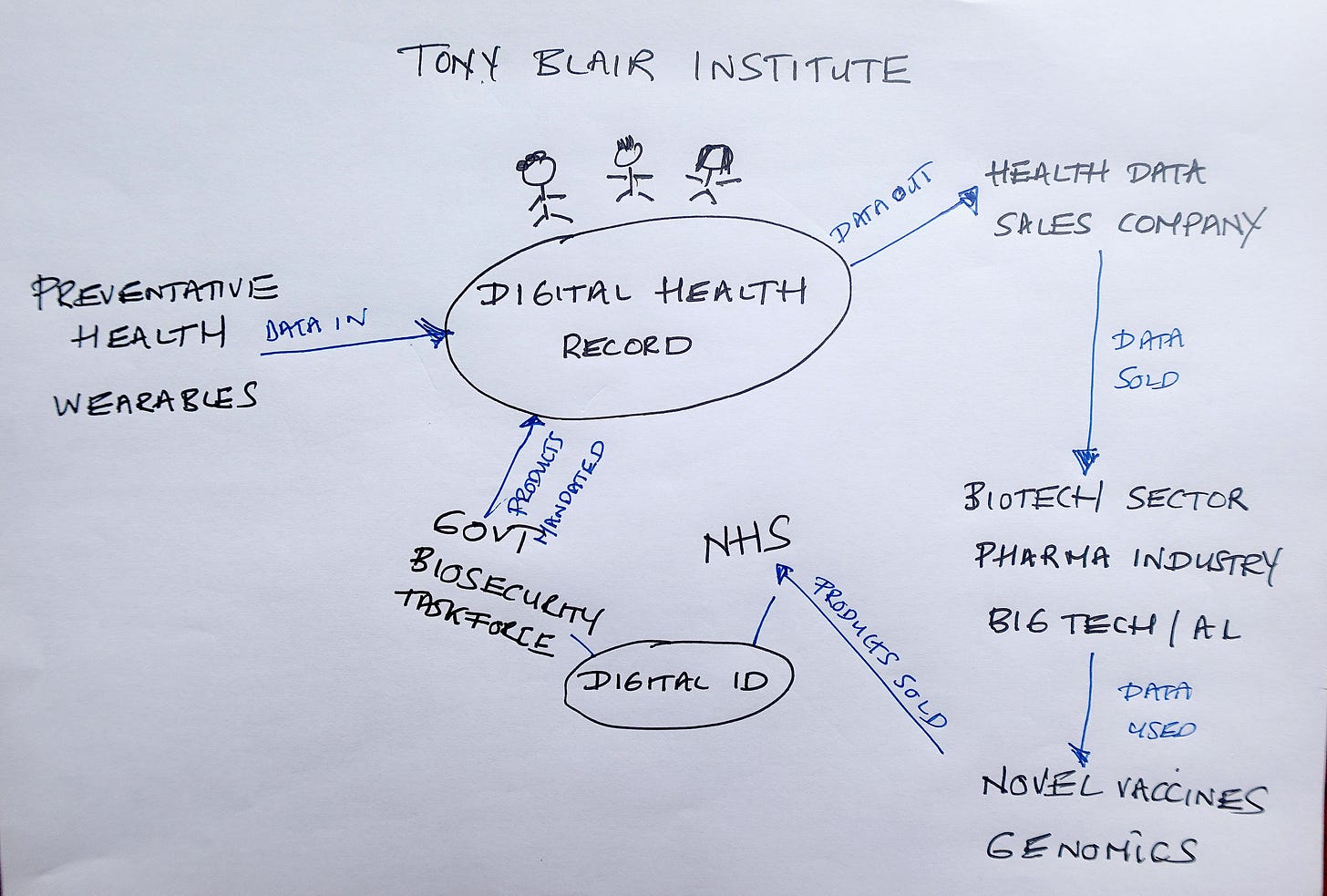

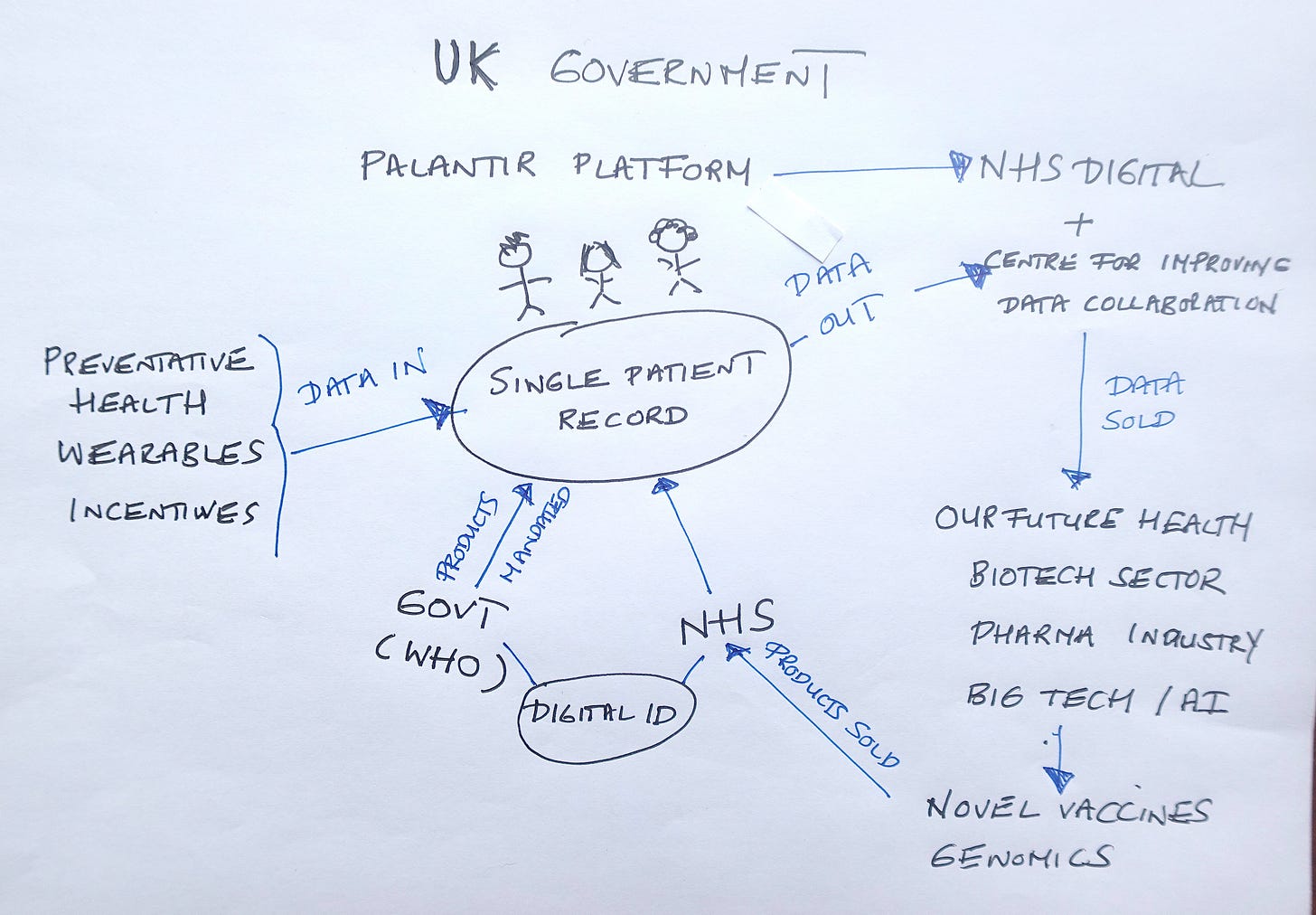

All this, as my punk flowcharts show, bears a close resemblance to the proposals developed by the Blair Institute. The Plan also contains key elements of a policy paper about health data written by the previous, Conservative government. See how well Blair works with the former Conservative leader William Hague! The consensus among technocrats is a salutary reminder that neither party loyalties nor the political values of former times help us to see where we are headed. Better to look at the policies. And here everything points in the same direction: biometric surveillance and pharmaceutical intervention.

What could be the motives for these extraordinary efforts to gain control of our health information?

Money.

Imagine the financial rewards if Pfizer's plans for annual Covid vaccines for years to come had succeeded. Even though they didn't, the wide and rapid distribution of the Covid vaccines in 2021 and 2022 earned the pharmaceutical industry revenues on a previously undreamed-of scale. The issue remains undiscussed by those charged with looking after our health and the public finances: no one, not the bodies charged with regulation, nor Parliament, nor the official Covid Inquiry, is talking about it. Instead, government and its associates are going full-steam ahead to create a new industry based on novel and preventative vaccines linked to genetic profiling.

Money, but that's not all.

Control.

All good technocrats understand that if you can connect the human body to centralised mechanisms which act as gatekeepers to the necessities of life – the ability to move around, earn a living, mix with other people – you've got the ultimate in external population control.

The EU has had plans for vaccine passports since at least 2018. The WEF started promoting the idea of a “health passport” for “vaccine free travellers” in 2020. Since Covid, the WHO and EU have established a Global Digital Health Certification Network to be used for “ongoing and future health threats”.

Real-time biometric data gathered from citizens' wearable devices, combined with the biometric border controls, would take this to a whole new level.

Control, but that's not all.

Genetics.

There's something else about population-wide health data that seems of immense value to technocrats.

It has to do with genomics.

To get control of human biology, to put organic life in the service of technology overseen by a powerful elite, is the ultimate goal of technocracy.

For the first time in human history, this is now possible. A former insider from the biotech industry told me: “We're at the point where DNA can be taken and spliced to create a Frankenstein's monster”. If combined with information about disease risks, behaviour and other traits gathered via the genetic profiling of certain groups, he went on to explain, this could be applied to whole populations. A drug to bring about genetic manipulation could be slipped into any medical product, “without a population knowing”.

And so we’ve arrived at the gateway to transhumanism.

When systems and processes that circumvent democracy become deeply embedded in governance, government becomes a conduit for policy that has already been decided elsewhere.

Recognising this gives us a better understanding of something that is flummoxing so many at the moment, both people in the pub and on social media and commentators in The Telegraph and The Spectator. Why is the current government so blatantly ignoring the will of the people on issues such as digital ID and illegal immigration? Why is it cutting benefits and services while raising taxes? And where – at a time that the UK's tax burden is higher than it's ever been – is all the money going? Why are billions being invested in AI projects while the infrastructure for the national water supply is collapsing and farms are going out of business at a record rate? Why is government orchestrating a process which will, according to the national energy operator itself, necessitate energy rationing?

Because, one way or another, all of these things help to create the new technocracy.

The only “political” task, as Blair's elucidation of leadership makes clear, is to persuade the population to accept these measures, whether through repetition and attrition or appeals to “progress”, “efficiency” and “convenience”.

And finally …

I'm going to end with an unfreedom mechanism that's almost funny in its blatant attempt to de-democratise Britain.

It comes from Demos - who knew a single think tank could be such a nuisance? and that report which attributed the unpopularity of Low Traffic Neighbourhoods to “misinformation”. Driving Disinformation ended with a dozen recommendations, one of which was that councils should be freed from their legal obligation to consult with communities.

The authors argue we should “Ditch the polling”: “National government should withdraw the statutory guidance to conduct representative polling to assess public support to avoid creating a form of direct democracy and undermining the voices of those disproportionately affected by policies.”

The reasoning that cancelling a consultative process will somehow make new measures imposed by the authorities more democratic may be contorted, but the intent is clear: if objections from local people prove an obstacle, do away with the channels by which people can express their views. Then the dissent magically goes away. Simples!

The next Substack, the last piece in The Hidden Mechanisms of Unfreedom series, will be published in September and cover fronts, trojan horses, deceptive images and manipulative language. It will also include an embarrassing tale of how I myself – and quite recently – almost fell for a mechanism of unfreedom.

This is such a clear and intelligent piece of writing, I hope it is shared far and wide. If anyone thinks the trans human side of things is not imminent and has not been planned for a while, here’s a link to a government paper on it, page 19 refers to human beings as, human platforms:https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/609d23c6e90e07357baa8388/Human_Augmentation_SIP_access2.pdf

Your piece covers so much ground; I can only comment on a small part of it.

Having had recent health issues, recently I've had a lot of contact with the NHS.

I'm amazed at their hopeless approach to patient privacy. As far as I can remember, there was a lot of online comment about the NHS leaking confidential patient data to commercial entities a while back. This may have been an opt in or opt out scheme on the part of patients, or via some kind of back door.

It seems that doctors and nurses actually have smartphones or other smart technology capable of picking up what people say in their offices! Yet, some parts of the NHS won't fully disclose essential patient data with certain other parts of the NHS on a less casual level. This unnecessary obstruction slows communication and can lead to errors.

I would not like to use any NHS or other online counselling services. Although NHS websites are good on the whole, I don't trust them.

More grist for the AI training mill, the promise of easy popular population control, and great profits for commerce. I thing ethical considerations are currently being left in the dust. AI or otherwise, technology is technology. What matters is how we use it