This August

The light and the dark

'The question is not what you look at, but what you see.' Henry Thoreau

We're on the brink of August - what I think of as 'immersion in nature month'. How very important this month is in Britain, with our long dark winters and slow springs. School's out and it's finally time for beach, festival or garden. For me, it's field. Our expectation of languorous days spent outside is more indicative of our needs than the reality - this is a season of sun that often disappoints.

This year like no other. 'What is going on with the weather?' The question carries an urgency, raising concerns about the exceptionally damp, chilly summer in the northern hemisphere which I won't address directly now. A watcher of the skies since I was old enough to tilt my head, I've taken to scanning the horizon for dark clouds and wondering about the criss-cross trails that periodically appear overhead.

All of which speaks to the light and dark side of our relationship with nature. British pagans are good on the idea that you have to grapple with dark forces in order to fully be in the world. Hanging out with druids while researching a book, I came to accept that the darkness of winter was not just something to be got through. Embracing the cycle of the year open the door to the more troubling idea that dark forces are part of the reality in which we live and, one way or another, must be dealt with.

We have all, to different degrees, had the experience of stepping into a building and feeling inexplicably uncomfortable or finding a new place exceptionally bleak. I notice this phenomenon with woods: some welcome you in while a few seem to have a kind of force field telling the human ‘stay away’. C S Lewis dramatised this in the Narnia chronicles when Prince Caspian galloped through a hostile forest. Like ghosts, these are common experiences largely ignored by our culture.

But the times are far more interesting than these encounters with the dark suggest. The easy paganism of the first sits comfortably alongside the mainstream practice of reconnecting with nature, extracting what we need and then returning to workplace and sofa. The more advanced recognition of the darkness in our world is a start, but only a start.

Because these days our relationship with nature is either up for grabs or on the turn. It's up for grabs in that there are powerful forces who want to harness it for their own purposes and - having come to dominate food production and healthcare – they're on the march for More. Our relationship with nature is on the turn because, as I suggested in my last Substack, we are at a point in human development where we could create a future very different and infinitely better from the reality we have experienced so far. If we make the right choices.

There are legion examples of what the issues are, right under our noses, in our everyday lives. Below, I offer two recent experiences that encapsulate them.

Solstice at Avebury

This year, for the first time, I did Summer Solstice properly. I went to Avebury, the stone circle in Wiltshire, to spend the night outside, with others gathered for the same purpose, and watch the sun come up on the longest day.

The weather was perfect, the people relaxed and the place possessed of a deep peace. There was indeed something magical about the stones and their capacity to shelter and nurture. Arriving early afternoon, we chose a particular stone as our base, leaving our bags and blankets in its shade and returning when tired. Over the course of the night we found that that the mineral flesh of Home Stone held a lasting warmth. Others felt the same way: person after person came and lent their head against the slab or put a hand in a cavity. 'This is my favourite stone,' explained one woman.

The heightened pleasure of being outside was partly due to the fact we were staying overnight. You know that lurking feeling when you're having a nice time but know that a journey lies ahead? It was absent: we were exactly where we needed to be. There was no noise: blasting pop music isn't done in pagan circles, nor is shouting. Instead, there was some gentle chatter and a bit of drumming. We wandered and then nestled against our stone.

But these were experiences were hard-won, wrestled out of a context of humanly-created stress. As we’d approached Avebury we’d found the roads lined with bollards, row upon row of plastic yellow sentinels starkly at odds with the surrounding greenery. The layby I'd planned to park the campercar and get a bit of sleep before the long drive home was sealed off with orange barricades. So was every other layby, fieldgate and possible place to stop within a radius of several miles. Even little residential roads were blocked off lest some sun-worshipper should think to park.

We eventually left the car in a secret spot and began the walk back to Avebury along perilous pavement-free roads, laden with bags, until a passing local took pity on us and gave us a lift.

It turned out that Wiltshire Council, working with the police and the National Trust, had decided post-Covid to close the area around sacred sites at Solstice 'for safety'. Visitors were encouraged to come by public transport but at Stonehenge even footpaths were closed for several days. At Avebury, once the National Trust car park was full, there was simply nowhere to stop. People defied the bollards and parked along the verge, some getting fines by way of a parting gift.

I've written a piece about this for The Critic which you can find here.

By a strange coincidence, a pocket of the rucksack I'd yanked from the back of the cupboard yielded a 2020 copy of The Evening Standard. The cover bore a picture of Dominic Cummings wearing a face mask. It evoked the memory of watching as two policemen crossed a deserted park to tell me, a lone woman sitting under a tree, that I was not allowed to be outside. And then I remembered talk from government ministers of banning the population from leaving the house 'for exercise'.

Who decides when and whether people should be allowed to spend time in nature? What happens when our relationship with nature becomes mediated and controlled? These are questions which will continue to face us in the coming years.

The Tail of Miss Meow

For background, my back garden in suburban London is a little piece of Narnia. Adjoining other gardens, allotments and a piece of woodland, it's attractive to wildlife and the back door that leads down to it is open most of the year. Over the years, the garden has hosted generations of foxes which I like to think of as the descendants of a vulpine orphan I helped to rear, a dynasty of robins and a host of local cats. Many of these creatures are Talking Animals: excellent communicators who let me know what I can do for them.

Some weeks ago, a black cat started visiting the garden and before long kept telling me she was hungry, in fact, starving. Wary of feeding someone else's cat and of making her dependent on me, I started to give her some of my own food (tuna, meat) when she really seemed to need it.

She was very skinny – could she be lost? I checked the local Facebook group. No obvious match emerged, but the search revealed a range of pictures of black cats from past months and years. They were followed by comments displaying the technocratic officiousness characteristic of much of the local community. 'Is it chipped?' said one. 'I can scan it'. Someone else volunteered to ‘catch it’.

Now, I'm aware that the RSPCA has a policy of 'euthanising' animals who overstay their welcome on its premises. I've also heard that black cats suffer from their historic association with witches and tend to get adopted less often than those of other colour.

No way would I turn my new friend over to the authorities. She would remain a free animal and I would support her as best I could. Little Black Cat spent a substantial portion of her day in next door's garden; my neighbour said she might be the pet of a local woman who had lost her job during Covid, become an alcoholic and abandoned her flat, which was due for repossession.

And so it is that between us my neighbour and I feed Free Cat and give her the attention she craves. My neighbour has bought her an outdoor house for rainy nights but, if my door is open, Miss Meow wanders in. Her new name derives from her excellent communication skills – a bleat for 'hello', a yowl for hunger and a whingy meow for 'I don't know what I want – maybe a cuddle'. Her most impressive meow is tentative, almost a whisper, made when she her visit lasts after my bedtime. It says: I'm sorry to disturb you but would you please let me out?

This story of care, cooperation and purring speaks to the light side of our relationship with nature. But its context contains a new order of darkness which partly explains my desire to keep the cat away from social services.

During the Covid crisis, the British government considered ordering the slaughter of the nation's cats. On learning this, I shed tears in a Lisbon park as I wondered which of the people I knew would have killed their cat.

Of course, in a nation of pet lovers many would refuse to comply. But Next Time resistance might be harder: since then, the government has passed a law ruling that every cat should be chipped ‘for safety’. New legislation also stipulates that everyone who keeps chickens must register their birds to be kept up-to-date with 'local avian disease outbreaks and information on biosecurity rules'.

As David Bell argues, we humans must have lived alongside avian flu for much of our time on earth, yet now an industry is being built around the idea that it poses an existential threat requiring mass culls.

Millions of mink culled in Denmark. The mass killing of badgers, or cattle because of the threat of tuberculosis. I don’t want, and am not able, to argue about the possible benefits of such an approach in the case of a particular disease; what I want to do is point to a trend and pose a question.

Is it possible that Western humanity, with its growing obsession with safety and control, is inflicting its own madness on animals?

There's a tale from the east which tells how, after death, humans pass before animals for judgement about how they have treated them. Maybe we don’t have to wait that long: in an echo of Macbethian gothic, the corpses of the Danish minks rose from their mass graves to trouble the authorities.

I'm just saying: let's pause before we go along with mass culls in the name of abstractions such as 'safety'. Scientific hubris, as people are increasingly realising after the past four years, tends not to pay.

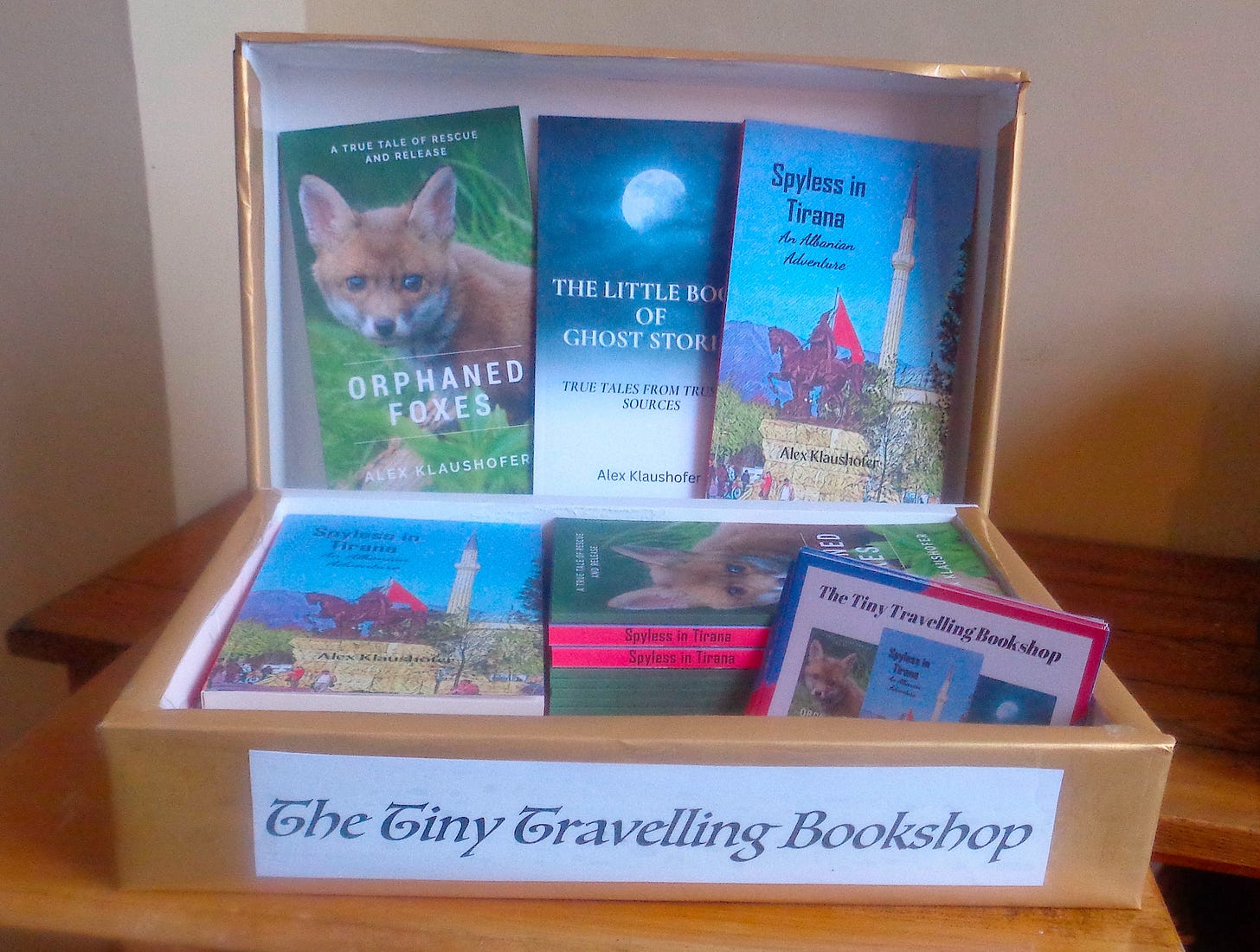

The Tiny Travelling Bookshop

This year, as I set off for The Field, I am taking a piece of commercial whimsy with me. It's a mini bookshop which I made myself out of a computer box and some gold paper. Its stock are my three physical 'midform' books: publications which are longer than an article but shorter than a full-length book.

It won't make my fortune, but the TTB will allow me to participate fully in the festival economy. This is a world of face-to-face trade in which people who make things directly connect with those who want to buy them. Some stallholders do take cards, but payment tends not to involve giving a fee and personal information to a third party. I even know of a festival where all transactions are conducted by barter. Everything is on a human scale.

I think this kind of economy – or some version of it, perhaps with technological improvements – would create the better future.

In spite of the obstruction by officialdom, I hope you enjoyed Avebury. I've just come back from an amazing camping holiday.

I agree with what you say about Winter and darkness. The cycle of the seasons actually reflects all aspects of the human psyche, and the changes for the better we can make for ourselves over the seasons and years. Celebrating the eight "Celtic" festivals - the solstices and equinoxes and those in between - as well as helping to reconnect us with the seasons can be used as a way of assisting self - development. Unfortunately our so - called culture has little interest in truly connecting with Nature, in spite of the fact that separation from Nature is one of the basic reasons why much of humankind is in such a poor state.

I've been to one or two places that don't want human presence. On the other hand, visiting an off the track piece of woodland or countryside frequently can enable relationship to develop between the terrain and oneself. This can lead to the area feeling welcoming and facilitate connection.

With regard to animal culls, it's hard to tell whether they're valid or the result of excessive zeal, or possibly some form of profiteering in some instances.

Also, I especially loved reading about your kindness towards that little black cat, and your frank discussion of animal culls. Can you imagine how Mother Earth must feel towards these little hapless ones who are mass murdered by humans for their "convenience." And we wonder why She needs to release all Her grief and anger in the form of fires, tornadoes, tsunamis and droughts.