Ways of heating

A practical post about reducing energy consumption and increasing self-sufficiency

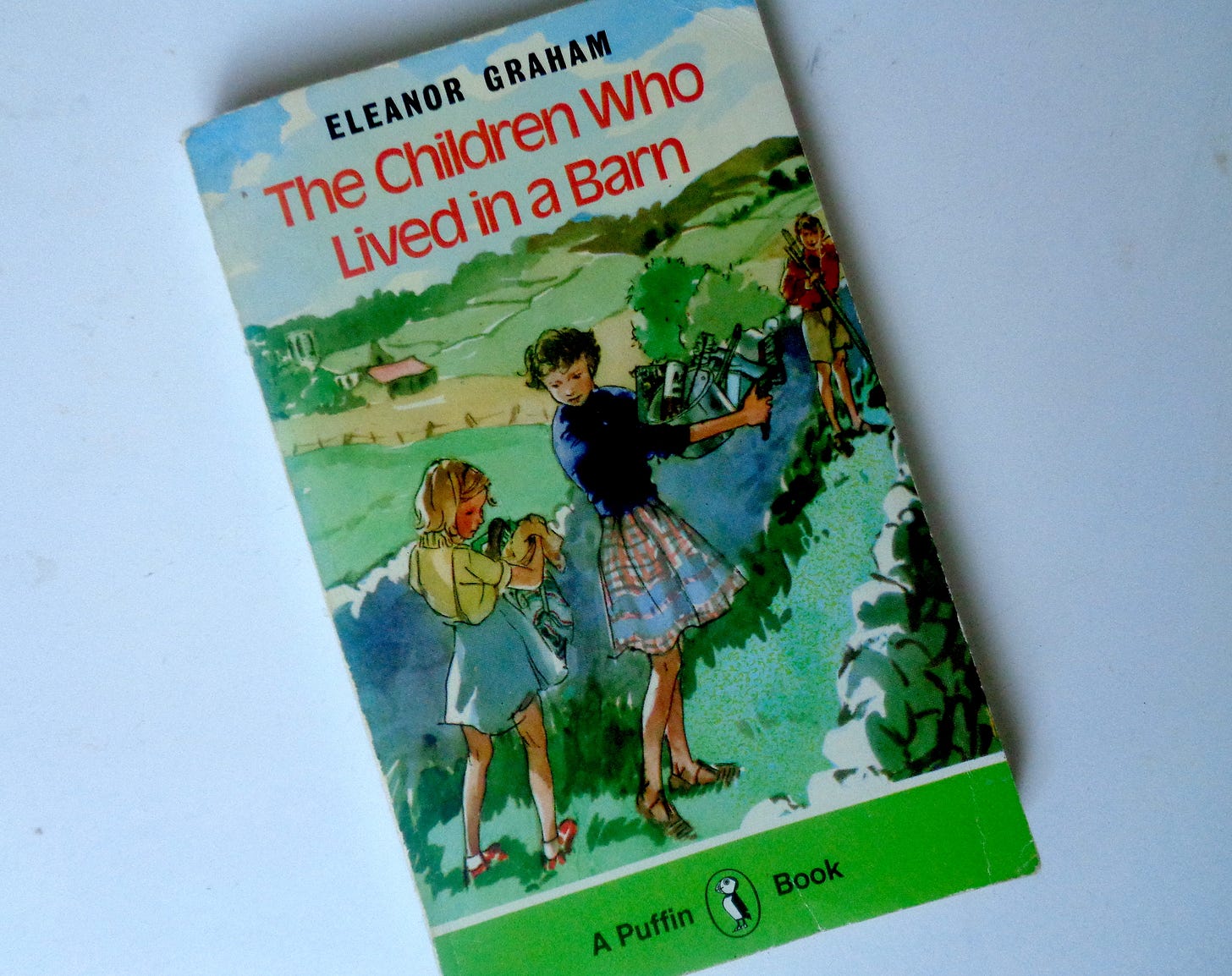

The summer-just-gone, while volunteering at a green festival, I attended a workshop on haybox cooking. I'd been carrying the image of a haybox – effectively a thermal stove which uses insulation to slow-cook contents that have been heated via hob or flame – in my mind's eye since childhood, when one of my favourite books was The Children Who Lived in a Barn.

Published in 1938, the book tells the story of how five children maintain their independence when their parents fail to return from an emergency visit to Granny. If the do-gooding ladies of their village get their way, the children will be split up and sent to orphanages and adoptive families. So, turfed out of their rented home, they take up the local farmer’s offer of a barn and live as best they can on a tiny allowance from their father’s bank manager.

I don’t know why, of all the vivid details in the story, the single image that endured over the decades was that of the haybox. The barn had only a stove intended for heating sheep dip, so cooking was limited and entirely dependent on wood gathered from round about. So when a local tells them about a contraption that turns hot meat and veg into a casserole over the course of the day, the children leap at the idea. The oldest boy makes a wooden box lined with newspaper and hay and from then on the children have a hot dinner when they come in from school. Somehow my child-mind latched onto this pleasing image of self-sufficiency and the bounty of natural processes long before I had any notion of utility bills or energy crises.

Back in the future, the funny thing was that as soon as the workshop leader starting speaking, I remembered I'd been using the same fuel-less method to part-cook for years. Sometimes I’ll start off a casserole and wrap it in a towel so that carries on cooking while I’m out. For the full process, the workshop leader advised taking whatever came to hand: a wicker basket or a cardboard box for the container and old duvets, sleeping bags or crunched-up newspaper for the insulation. In her experience, hay did not work well, and neither did wool (a remark that generated some workshop politics when an attendee left in disgust, afterwards telling me she wasn’t going to take any lessons from someone who was ‘negative’ towards wool.)

My initial efforts at haybox cooking met with only moderate success. My haybox is a polystyrene box with a fitted lid that I found with the discarded cardboard outside a local shop. An oblong cushion that had been made by my mother covers the casserole and is an exact fit. But while everything I put in to the box, from boeuf bourguignon to homemade baked beans, was cooked, the result had more liquid than I was used to and wasn’t particularly hot. Part of the problem was the insulation: in the spirit of using whatever comes to hand, I'd been wrapping the pot in a swathe of lining fabric. It isn’t thick enough: a towel is better. I’d also disregarded the instruction to bring the pot to the boil with the lid on. The results from actually following the advice have been better and I’ve come home to the smell of a stew which has spent less than twenty minutes on the hob.

Those new to hayboxes will gradually find the materials and methods that work for them: just as in cultures where traditional dishes vary according to the cook, everyone has their own recipe. If you want to give fuel less cooking a go, you’ll find a demonstration video with the workshop leader Jane Segaran here, and further advice about from wartime food leader Utility Jude here.

In these strange times, it seems to me that as one crisis morphs into another, and politicians and public figures continue to announce new threats to life as we know it, one of the ways forward is taking small steps to resilience. Amid all the complex issues and ideological abstraction, such steps are a reminder to body, mind and soul that everyday life for us as biological beings is about meeting our need for food and shelter in a way that involves constant contact with the material world.

While many of us have retreated into offices and computers with the expectation that if we do the right thing, society will provide for us, the off-grid movement has lived by a different understanding. Despite the obvious costs in terms of effort and labour, the path of self-reliance is testament to the satisfaction and sense of safety that can come from self-sufficiency. And yet ‘self-sufficiency’ is the wrong phrase: this way of life is a reminder that we depend on nature, are provided for by nature, and are part of nature.

Perhaps this is why many of us take such a pleasure in unnecessary camping, leaving comfortable homes to go and lie on the ground and cook outside: we’re maintaining our skills as humans living on the earth. I’m aware that my own camping adventures, which include creating a powerless fridge in a hedge and making coffee with a Kelly kettle (a device which brings a cup of water to the boil on a handful of twigs), are a kind of adult play. But then again, it’s important to remember that play is really about learning and preparing for the future.

As an instinctual response to crisis, the impulse to greater self-sufficiency is coming into its own now. As I wrote at the end of the last Bafflement Essay, more and more people are taking part in what could be called The Great Disconnect, seeking sources of food and energy that are closer to home and free them from dependence on complex supply chains, shifting geopolitics or increasing control by the state. Or perhaps all three, as in Sri Lanka now, where petrol can only be legally obtained if you scan your QR code to get your ration.

‘It seems we’re supposed to be dependent for everything,’ observes a friend not given to political commentary. Indeed, whatever your perception of the reasons and causes behind where the Western world is now, modern trends seem to be weaving an ever-tightening net. A few years ago, I saw a Facebook post by a young mother whose fridge had just broken. Her panic leapt off the screen: from the way she was writing, it seemed as if she genuinely believed she and her children would perish if a new fridge was not delivered within the next few hours. Around the same time, my late godmother reminded me that she had grown up, before fridges, in a genteel household where food was preserved in the larder on the cool side of the house. So much progress in a few short decades!

For me, raised by a mother who thought she was Mrs Beeton (I inherited three copies of The Book of Household Management), the epitome of our growing dependence is HelloFresh, a company which delivers meal kits to your doorstep. The main selling point is that you don’t have to think about what to eat or engage much in the process of producing a meal: having ordered the week before, a short time before you want to eat dinner, you simply take the ingredients from the packaging and follow the instructions on the recipe card. ‘I love not having to decide,’ gushes one of the customers that keeps coming up in the YouTube advert. ‘Everything I need comes in a box,’ rejoices another.

The advertising takes a contemporary spin on the old-school marketing of identifying a problem and then offering a solution. The ‘problem’ is the incapacity to cook, either because of a lack of time or a lack of confidence in dealing with food. It plays on the fear of producing a meal that others won’t like: the ‘delicious’ recipes, described with fusion buzzwords such as ‘jasmine rice’ and ‘hot salsa’, are bound to make your family love you! In this childlike form of cookery, most of the thinking and risk has been removed: you don’t even need to decide on quantities, as the meals come ‘pre-portioned’.

Better, by far, than dependence and de-skilling, is an approach that requires creativity and maintains an easy relationship with the stuff of life. In the UK, a diet of celebrity and competitive cookery programmes has fostered the idea that producing a proper meal is difficult. But there’s skill and pleasure in throwing together a pottage or creating a dish, Ready Steady Cook style, with whatever is in the fridge and cupboard.

So in the face of an energy crisis which promises to last for the foreseeable future, not for me another gadget such as an air fryer, yet another example of a consumer society’s ‘solution’ to a ‘problem’. Instead, I’m taking small steps towards greater self-reliance which draws on the innate practical wisdom which has been central to human life since its beginnings.

We can do this life-thing, you know, with or without the global forces that increasingly plague us.

Thank you Alex as always very informative.

Love and light Muna 🦋🙏🏽💜

a) I remember that book! I haven't thought about it in years and years!

b) Bog off, Hello Fresh :-)

b) I have one of these: https://www.wonderbagworld.com/ I don't use it much because I'm not very organised when it comes to cooking - I tend to do it very last minute. I've mainly used it for making yoghurt. But your post is inspiring me to dust it off and start cooking my stews in the mornings!