Whose cash is it anyway? Bafflement Essay #7

On the headlong rush towards digital currency and digital ID

‘We are on the heroes’ journey, and the first step is sorting. You have to sort out what's real and what's not real, what has meaning to you, and what no longer has meaning to you. Then you will have challenges that you have to accomplish and you'll think: “I can't do it. I don't have the power.”

But there'll be something inside of you that rises to that challenge and at the critical moment, you'll be fine. That's the inner knowing of the self.’ Penny Kelly

This is the first of two essays taking a deep dive into two aspects of the digital revolution that are proceeding apace with huge implications for the way we live. In this, the first baffle, I want to take a look at the drive towards digital currency and digital ID that has been accelerated by the Covid crisis. (This post is long, so best viewed online.) Later, in a second essay, I'll face – if you'll pardon the pun – up to ideas from the increasingly vocal transhumanist movement, something worrying many since its advocates started openly promoting a merger of the human with the synthetic as our one-and-only-future.

It turns out that, unbeknownst to many of us, such technological developments and their social and political applications have been in the pipeline for some time, so it’s perhaps more accurate to say that these trends have been revealed by the Covid crisis. But for now, let’s just note that around half the world's governments are looking into introducing a central bank digital currency or CBCD, a digital version of fiat money which would be issued and regulated by the state.

Ten countries have launched a digital currency so far, with China expanding the pilot project it's been running for the past two years. In India, the government aims to have a digital rupee in place by 2023, when the European Commission also plans to introduce legislation for a digital euro. In the US, a recent executive order from Biden has made research into a CBDC a priority, while in New York a pilot for a digital dollar has just begun.

At the same time, governments and organisations such as the European Union are pushing for digital IDs to become the main way citizens interact with the state and access services. Remember Lucy, whose day starts with making an appointment for mandatory vaccination and ends with showing a QR code to get into a bar? It will all be thanks to the digital wallet the EU has commissioned from Thales. Leading the digital ID race is India, which started the rollout of its biometric system Aadhaar in 2009. Now, with most of the country’s 1.3 billion population having exchanged finger prints, iris scans and photos for a 12-digital unique identification number, digital ID is effectively compulsory for participation in Indian life. But the system’s path has been fraught with controversy, with privacy breaches and people being denied access to services, in some cases costing lives.

There are suggestions that the two systems should become linked. At a recent meeting between the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank Groups, speakers agreed it would be good if CBDCs and digital ID were paired ‘as a package’. Where adopted, such measures would potentially affect every aspect of an individual’s life, right down to details that have hitherto been considered private and personal, creating a completely different kind of society.

Yet – and herein lies the main area of bafflement – there's an almost complete lack of public debate on the subject, at least of the kind customarily led by politicians and institutions. The mainstream commentary on CBCDs and digital ID by the media and think tanks rests on the assumption that such developments are inevitable, part of the progress towards a future that’s already written. It focuses on the benefits, citing the ‘inclusiveness’ and ‘resilience’ of a digital currency and the ‘convenience’ of digital ID; only passing references to privacy concerns leaven the sympathetic coverage of the ‘challenges’ facing governments as they strive to create the new systems. Meanwhile, a minority of the public, independent media and civil liberties groups worry about the unprecedented potential for control afforded by this digitalisation of our world. It's as if two parallel discourses are being conducted by two sets of people with entirely different interests, with little or no dialogue between them.

I want to suggest that the divide in the discourse about the digital reflects a very real split between institutions and people, one that has accentuated sharply over the past three years. On one side are governments, the finance sector and their allies in supra-national organisations; on the other are citizens, the individuals and ordinary people who make up civil society. And in a discourse dominated by the first, more powerful group, there’s an occlusion of the fundamental questions. Will these developments promote human flourishing? Are they in the interests of ordinary people? What do they mean for the rights and freedoms that have long been taken as central to a good society?

Such questions don’t even rise to the surface, so buried are they under a narrative of inevitability which suggests that modern life is so entirely subject to the impersonal forces of technology and progress that there is nothing to discuss.

Personally, I don’t buy this tale of inevitability for a moment. I don’t believe that we humans have no control over our way of life and the kinds of societies we create. And – full disclosure here – in the absence of a genuine public debate of the kind central to a functioning democracy, I'm on the side of the people. In what increasingly looks like a rigged game, I suspect we are being led in a direction that is not in our best interests.

So if things continue down this path, what might go wrong?

II

Let’s start with the main ‘people's concern’ around CBDCs. Unlike cash, a digital currency exists in a network beyond the control of the person who owns the money, and is run by third parties: the (central) bank and the companies which facilitate the financial transactions. With the currency’s architects and managers acting as mediator, there is no way for buyer and seller to exchange outside this system. This key feature of digital currency gives rise to its programmability, the fact that the controlling body can set things up so that the money could only be spent in a certain way or within a certain timeframe.

Discussing the possibility of a CBDC in the UK in 2021, Sir Jon Cunliffe, a deputy Governor at the Bank of England, said that programming a digital currency for commercial or social purposes is something the British government needed to consider: ‘You could think of giving your children pocket money, but programming the money so that it couldn’t be used for sweets,' he said. ‘There is a whole range of things that money could do, programmable money, which we cannot do with the current technology.'

You could almost miss it, this casual reference to the state controlling the way citizens of a liberal democracy spend their money. In fact, if I hadn't had a coffee on this rather sleepy afternoon, I might take it as just another example of the growing paternalism of financial institutions in my native UK, where it’s become common for banks to ask you why you want to make a withdrawal and ever-tightening security measures make it more likely your card will be blocked without warning. ‘We have a duty of care to your money,’ said a woman from the Coventry Building Society as she explained why I could not access my savings account from Portugal. However, she added kindly, if I was in financial trouble I could write to the directors of the society and they would ‘look favourably’ on my application for funds.

Elsewhere, financiers are openly considering limits on how much digital money people should be allowed to spend if they want to avoid data collection. Fifty euros per transaction and a monthly spending limit of €1,000? wonders Fabio Panetta of the European Central Bank. The proposed measures mimic regulations already in place to ban cash payments over a certain amount: in Portugal it is illegal to exchange more than €3,000 while in Greece the limit is a mere €300. Cash or digital, if governments have their way, it seems they will monitor most of our spending like parents overseeing their children’s pocket money.

But perhaps I’m being too flippant, and risk ignoring the good reasons why governments and banks feel they may need to control peoples’ spending. Life and planet-saving issues are at stake, notably the central one in the age of climate change: carbon.

That might explain why, a few months into the Covid crisis, the World Economic Forum came up with the idea of the CovidPass, a vaccination passport it claimed would be the key to reopening global travel. The benefits of the pass would extend beyond disease control to include ‘mandatory carbon offsetting for each flight passenger, to preserve the environmental benefits of reduced air travel during the crisis’.

Two years on, the WEF is saying that the time for carbon allowances – rationing individuals’ air travel – has finally arrived. Until recently, writes Mridul Kaushik, there was no appetite for such a measure: ‘There have been numerous examples of personal carbon allowance programs in discussions for the last two decades, however they had limited success due to a lack of social acceptance, political resistance, and a lack of awareness and fair mechanism for tracking “My Carbon” emissions.’

But everything, he notes with pleasure, changed with Covid:

‘COVID-19 was the test of social responsibility. A huge number of unimaginable restrictions for public health were adopted by billions of citizens across the world. There were numerous examples globally of maintaining social distancing, wearing masks, mass vaccinations and acceptance of contact-tracing applications for public health, which demonstrated the core of individual social responsibility.’ In other words, given the right reason, the Covid crisis showed that people will accept more restrictions than policymakers ever previously dreamed possible.

But wait. When I do some basic research into the business of carbon offsetting – an area that, to be honest, I’ve never given much thought before – I find that it’s fraught with doubt and vested interests. The idea of a carbon footprint dates from 2004, when oil giant BP launched its carbon footprint tracker with the help of advertising firm Ogilvy and Mather. While compensating for one’s carbon use quickly caught on, within a few years it emerged that carbon offsetting schemes were being used to salve consciences while business went on as usual. In a 2007 piece for The Guardian, investigative journalist Nick Davies found that voluntary carbon offsetting schemes were unreliable at best, exploiting customers and damaging indigenous communities at worst. At few years later, a four-month investigation in the US found that ‘individuals and businesses who are feeding a $700 million global market in offsets are often buying vague promises instead of the reductions in greenhouse gases they expect.’

At the time, environmental organisations such as Greenpeace were reluctant to reject carbon offsetting altogether, calling instead for tighter regulation and better standards to ensure that the complex criteria needed to bring about genuine offsets were met. But fast forward to 2021, and Greenpeace calls greenwash: ‘Whether you are filling up at the pump, booking a flight or simply browsing supermarket shelves, you are being targeted by marketing campaigns trying to persuade you that everything is fine … Offsetting has become the most popular and sophisticated form of greenwash around. It could work in theory, but in practice, it's riddled with flaws.’ Writing for Greenpeace the same year, Chris Greenberg goes even further. Carbon offsetting is a scam, he says, ‘a bookkeeping trick’ that ‘feigns compassion’ and ‘preys on fear … Offsetting is bad for people and for the planet.’

The puzzle, then, is why there is so much enthusiasm for carbon offsetting among politicians and financiers. As UN Special Envoy for Climate Action in 2020, former Governor of the Bank of England Mark Carney set up a private sector task force to ‘scale up’ the voluntary carbon offset market to tens of billions of dollars per annum, a move denounced by green activists as a ‘scam’.

The Australian Commonwealth Bank, in partnership with fintech start-up CoGo, has just created the first app allowing customers to get personalised carbon footprints of their spending and then buy carbon credits to offset it.

It seems that the ‘reason’ for introducing measures to curtail freedom of movement comes from the private and finance sectors rather than environmentalists. At the COP 27, there was enthusiastic talk about how carbon credits are soon going to become part of the finance system. ‘Carbon is moving very quickly into a system where it’s going to be very close to a currency,’ said former Bank of England advisor Michael Sheren. ‘Basically being able to take a ton of absorbed or sequestered carbon and being able to create a forward-pricing curve, with financial service architecture, documentation.’

Link this to a programmable CBDC, and we are on the territory of a social credit system.

III

We don’t need to speculate about a dystopian future to get an idea of what a social credit system might be like. We have China.

Designed somewhat ironically to address a crisis of trust, the country’s social credit scheme aims, according to the founding document published by the State Council in 2014, to ‘allow the trustworthy to roam everywhere under heaven while making it hard for the discredited to take a single step’.

Launched through a series of pilots in various cities, the system draws on a web of information held by many different institutions to deduct points for behaviour that demonstrates a lack of ‘trustworthiness’ and award points for being a good citizen. People can lose points for bad driving or the late payment of a a bill, and receive points for service to the community. Penalties for a low credit score include travel bans: by the end of 2019, the authorities had stopped 23 million people from buying flights, according to the National Public Credit Information Centre. One lawyer travelling for work found himself unable to buy a ticket to return home. And, as part of the name and shame aspect of the system, a blacklist of those with low scores and a red list of those with high is available as a publicly-searchable database.

Although the government has promised to make it nationwide and compulsory for everyone, so far China’s social credit system is voluntary and piecemeal. In the meantime, the use of Covid apps provide a foretaste of how it could work when fully operational: citizens are banned from taking transport and going to work unless their phone shows a green code that needs constantly updating with Covid tests.

Outside China, governments have already used their digital muscle to freeze the bank accounts of those whose activity they dislike. In 2015, the Indian government stopped Greenpeace and dozens of other non-governmental organisations from accessing their funds, while in Canada in 2022, the bank accounts of those connected with the truckers’ protest were frozen.

When convoy leader and former military officer Tom Mazzaro had his credit card blocked, he couldn’t buy the medication he needed for his son’s heart condition. Luckily, his wife had cash available to pay the pharmacy, but the experience has heightened his awareness of how the Canadian government could use digital ID. ‘If we do digital ID and wrap this all up in your money, you’ve got the ability to shut off all means of earning an income,’ he tells the YouTuber Clyde. ‘You might disagree with the government. You do it as an individual and you’re going to have everything shut off; you may not even be allowed on the internet to tell your story.’

‘Digital ID is really a symptom of a giant sickness that we have on the part of our government,’ he continues. ‘They want to box us in at every turn. They want digital ID so that if you have wrong think, they can basically exclude you from society.’

Concerns about the rise of a social credit system in the West paralleling that in China have been growing since before Covid. Writing in 2019, Mike Elgan highlights how the Big Tech firms of Silicon Valley started monitoring customers’ behaviour on social media to decide whether they were entitled to goods and services. Recently, the use of extra-legal social credit measures has accelerated as private companies take censorship into their own hands. In September 2022, PayPal abruptly closed the accounts of several organisations in the UK, including the Free Speech Union, apparently because the payment platform objected to ideas expressed by the organisations. PayPal also tried to introduce new terms to its Acceptable Use Policy which would allow the company to fine users $2500 for posting materials that it considers ‘objectionable’ before rolling back in the wake of public protest.

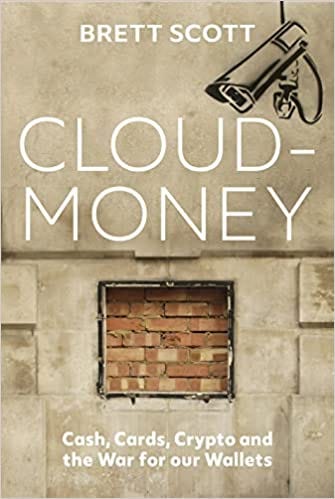

The transaction surveillance and transaction censorship enabled by digitalisation is already here, and it is up to us to let corporations and politicians know how we feel about it. As the author of Cloudmoney Brett Scott says: ‘Digital money underpinned by the banking sector is laying the foundations for the next stage of both US-dominated surveillance capitalism and its Chinese counterpart.’

IV

Meanwhile, as we ordinary folk go about our days, doing a food shop here, buying a coffee there, most of us barely notice how we are gradually moving towards a 'cashless society'. In Bafflement Essay #6, I described my shock at how fast retail and hospitality sectors in the UK are switching to digital-only payments. Swiping their smartphones and contactless cards, most people seem to accept the change without question, sometimes saying they prefer the convenience of not having to carry cash. The arguments about how digital payments exclude those without bank accounts seem to have been forgotten by the socially-minded who, just a few years ago, were stressing the importance of financial inclusion. There is little concern about the erosion of the informal economy that depends on spontaneous transactions: the fetes and fayres, the odd jobs and pennies-for-the-guy, the donations to the busker and the homeless which make up the fabric of community life.

This lack of attention to the downsides of digital money is part of a deliberate strategy to ween people off cash, according to Scott. Banks, payment companies and fintech start-ups stand to gain commercially from the death of cash, while governments are keen on maximising tax revenues and the power to ban certain financial activity. So it’s not surprising that these converging interests have formed a powerful coalition to persuade the public that digital is best. The resulting communications strategy draws on the superficial appeal of cashless payments and, says Scott, ‘showcases the surface-level “feel” of digital payments – their slickness or apparent convenience – rather than drawing attention to the deeper structures that underpin them.’

The strategy builds on the surface convenience of digital transactions to create a sense of inevitability through the inverted suggestion that the demand is coming from us, the people: ‘Pundits claim that a cashless society is inevitable, because ‘we’ – the members of the public – see the value in ever-increasing speed, automation, connectivity and convenience, and want ever more digital finance. Because ‘we’ all want this, no individual dissenter can stand against it, and if they try, they will be left behind,’ writes Scott. ‘This messaging is reinforced by an entire marketing industry that specialises in telling us to get ready for the change we are apparently driving, lest we are bypassed by a ‘rapidly changing world. This messaging accompanies almost all products pushed out by finance and tech companies, presenting commercial interests as natural forces, unstoppable and benevolent for all.’

Yet what is really going on is the creation of a global digital empire run in the interests of those who are setting it up: the financial institutions, multi-national companies, governments and big tech firms who have entered into partnerships based on shared interests. And with its need for ongoing growth, such a behemoth will continue on its expansionary path, ever on the lookout for new products and markets in its drive to make more money.

Such a situation already unfolding, argues Penny Kelly, a writer and polymath who grew up homesteading. ‘We have allowed the economic sector to get totally out of control. The result is that a handful of people have taken all the money and run out of places to put their money. When you are out of businesses to invest in, you start looking around to see “what else can I get into?” So the investment has been into the medical field and the attempt has been to get control of that medical field in order to make it a profit centre. That means we are the product.’

‘At the some point, we the people have to step back and say: “wait a minute, we cannot allow all the Gateses, Bezos, Buffets, Rockefellers to commandeer all the money”, she continues, pointing out that as the rich minority continue to buy up the natural resources which provide food and water, ordinary people will struggle to meet their basic needs.

And among ordinary people there are growing levels of discomfort at the tightening web of digital control. Why then is there not more vocal concern? Scott suggests that it is psychologically easier to go with the flow and accept the rationale of the inevitable march of progress: 'Because that new situation is getting baked in as the default in all systems – for example, parking meters suddenly ‘go cashless’ – trying to use cash in that situation will very much feel active, like trying to maintain posture: the cash user increasingly feels out of sync, as if resisting a tide. That gets strenuous, so it is easier to just let go and sync up. The latter is a passive process, but one that will be reported on as an active consumer choice.'

‘We’ll get used to it, like everything,’ mutters a friend of mine as she swipes her card to pay for our two drinks.

I’m sitting on the sofa with my neighbour in London. She’s had a difficult morning, since the car park of the clinic she was attending was cashless and had refused all her cards. She had to park further afield, running back to the clinic with the baby in the pram. I tell her that, for face-to-face transactions, I’m now cash-only. She’s incredulous. ‘But there are so many places round here that are card-only. Aren’t you left out?’

Not as left out of our own lives as we’ll all be, I don’t reply, if the corporate digital takeover succeeds.

V

So if we don’t like the future being laid out before us, what can we do?

The first step, says Kelly, is to take a good look at what is and decide how you feel about it.

‘Use the old rule of thumb: how are you feeling? How are things working for you? What are the results of what we see happening out there?’ she suggests. ‘The old ethics that used to guide us are not guiding us any more. When you have a corrupt leadership that has set the tone and the tone is one of “you don't matter”, and the behaviours demonstrate being cornered, tricked, used, defrauded, the rights that we had disappearing left and right, then you can say, “what's wrong with this picture?” And so you look first in the box to see what’s actually going on and then you can begin to say “what would we rather have?”’

For author Zeus Yiamouyiannis, it’s essential to understand the mechanisms of societal manipulation. Typically, a campaign to further corporate and political interests appeals to people’s sense of the good, taking an idealistic aim such as saving the planet or promoting health and using it as a persuasive tool. ‘They appeal to your empathy, to your sense of open-mindedness, inclusiveness and compassion to force you to respond to their predatory or parasitic behaviour and cave to their demands,’ he says. ‘That is an extraordinary tool on a personal level, but it’s also an extraordinary tool media-wise, communication-wise and propaganda-wise.’

‘We are taught to create an empathy with powers that are going against our own interests and our own sovereignty,’ he continues. ‘They’re trying to convince us that if we are good people, our choice ought to be the choice that they would make for us. That’s a very powerful inducement to people who do have a conscience – there’s a vulnerability there, almost an innocence, and that’s predatorily taken advantage of.’In the push towards digital money, commercial and political interests are turning crypto currencies, which have the potential to become ‘radically democratising’, turning them into something ‘radically tyrannising’: a CBDC attached to a social credit system.

With interviewer Regina Meredith, Yiamouyiannis takes the now-notorious World Economic Forum video featuring the mantra ‘you will own nothing and be happy’ as an example. Ostensibly, the film advocates idealistic aims: a global society in which property ownership has ceased to matter and, in order to help the planet, people consume less meat. But in reality, the purpose of such publicity is to help create a market for processed foods produced by multinationals, while the future society envisaged is not one free of ownership but one in which most land and property would be owned by large corporations. The wider context reveals the indications of such a goal: the talk of local food production in a WEF press release is belied by the fact that the WEF Food Innovation Programme is backed by CEOs of large multinational corporations. Meanwhile, Bill Gates, a supporter of the programme, has been buying up large swathes of American farmland.

Always look for the motive behind new, life-changing suggestions, advises Yiamouyiannis. ‘Don’t go for the language – they’ll always use inclusive language. Look for what they’re actually trying to accomplish. Are they trying to turn you against your own deeper intuitions and instincts about what is right in a situation and overwhelm that?’

In this piece, Jem Bendell invites us to consider how people were misinformed about the Covid vaccines to serve profits and power: ‘Most of the arguments that the vaccine ‘hesitant’ were selfish and dangerous were actually corporate-profiteering memes implanted in the brains of people who didn’t think critically. The way this was done was through trusted media,’ he writes. ‘All of us can all explore where we got our information from and why we reacted in the ways that we did … let’s realise that our desire to be smart, correct and ethical is actually the way that we can be most manipulated by mass media and authorities.’

Once the painful work of recognition and introspection is done, action can begin. For Kelly, an exponent of the New Earth thinking that anticipates a period of transformation following a difficult transition, what is needed is a double approach: ‘Create some mental boxes. In one, you put all the stuff that is dying, when you recognise it. In the other box, you would put the stuff [that] looks positive, promising, may be helpful.’

Then start taking steps towards self-sufficiency, learning new skills and connecting with others, moving in the direction of ‘the restoration of life’. This, she suggests, is the remedy for the sense of powerlessness so many are now feeling: ‘Once you begin to look at life in that way, you begin to walk with one leg in each world, and one world is the easy world, it’s the world of comfort, the system. The other world is the world of self-sufficiency. How do you begin preparing to be self-sufficient? Once you take that on, there’s a sense of power, a sense of “I'm doing something”.’

You will be far from alone. ‘There are people all around the planet who are basically ignoring the mess that is,’ Kelly goes on. ‘They're busy creating new governance structures, new financial structures, new family structures, new kinds of food, new ways of doing medicine, new artistic applications, new kinds of science, even. There are people who are putting things into motion.’

Meanwhile, there are signs that the people being offered the first centralised digital currencies are indeed following their own instincts and intuitions. Having banned cryptocurrency, Nigeria is having trouble persuading its citizens to use Africa’s first CBDC: ‘eNaira is seen as a proxy for the challenges facing the continent’s biggest economy and a symbol of distrust in the ruling elite.’

Fantastic piece… I’m old enough to remember when you could get this level of insight, intellect and analysis in the MSM. No longer. Cash is king, the king is dead, long live the king!