To be honest, until recently I haven’t given taxation much thought. On the whole, I've accepted the platitude that, “like death”, taxes are inevitable.

As a modern British citizen, my governing assumption has tended to be that the purpose of tax is to pay into a collective pot for shared services. It's a bit like my local community choir when it started out – we used to pay £3 a session to cover the room hire and sheet music. The arrangement derived its legitimacy from transparency and trust, and I didn't mind when the fee went up to £4 to buy the music director a new keyboard.

This view of taxation prevails on a national scale: taxes exist to build and maintain infrastructure, provide services and generally create the good society. Like in my choir, the arrangement is underpinned by trust, and that trust means that not too many questions are asked when changes, usually in the form of tax rises, occur. I'm reminded of a caller to a radio phone-in about council tax. The presenter put it to her that, since the council had run out of money, taxpayers needed to pay more to keep libraries and leisure centres going. The caller agreed, adding that she “had no choice”. She sounded sad, defeated even – but at least her fiscal worldview was intact.

As a responsible citizen of the post-2020 kind, I've decided to clean up my act. Taxes form the financial foundation of the modern state. They're what make Western society, with its complex network of services, entitlements and obligations, possible. As such, they're an integral part of the social contract and their legitimacy depends on honesty and consent. In 2024, with my eyes wider open than they've ever been, I'm minded to ask whether my assumptions about taxation hitherto are well-founded. Have I perhaps been too passive, too incurious about this great fiscal system of which I'm a part?

I think there's a need for greater tax literacy, and I'm going to start with myself.

A little bit of history

Income tax was first introduced in Britain to fund WAR.

Imposed during the 1790s as a temporary measure to pay for the war against against France, income tax was initially highly unpopular and widely evaded, especially among traders and manufacturers. It was seen as an unacceptable intrusion into people's private financial affairs. But in time, paying income tax came to be considered a necessary evil, even a patriotic duty, to defend the country against Napoleon.

The Liberal government of the early twentieth century brought about a change in the purpose of taxation, shifting from a means of paying for war to a way of supporting the welfare of the people. At that point, only the richest paid income tax but by the end of World War II, the majority of working people had become taxpayers. In 1944, the Pay As You Earn Scheme was introduced, a system of deducting tax at source to ensure the state automatically got a share of people's earnings.

Corporation Tax on company profits and Capital Gains Tax were introduced by Chancellor James Callaghan in 1965. In 1973, when the UK joined the Common Market, Value Added Tax replaced purchase tax. VAT was a continental invention, based on ideas developed in France and Germany to enable the state to skim off money from every stage of the production process. Since its introduction at 10%, VAT has gone up across Europe: it's now 19% in Germany, 20% in the UK, 23% in Portugal and 25% in Denmark and Sweden.

To be honest again, I was surprised to learn all this. Looking at the history of taxation has given me a degree of detachment from what is, and what strikes me most is how tax is clearly used to raise revenue for leaders' grand projects. It’s also notable how a taxation system, once in place, seems to expand, demanding more and more from the citizenry. My shift in fiscal perspective is underway.

The taxes we pay

A misperception I've harboured much of my life is that tax is mainly paid on income. It's a common misperception from which follows the idea that if you don't earn much, you don't pay much tax.

In fact, in modern Britain everyone pays tax, in multiple ways and usually on a daily basis. Below is a list of all the taxes I can think of: if I've missed any, feel free to add them in the comments below.

Income tax

National insurance

Council tax

VAT

Road tax

Fuel tax

Flight taxes

Excise taxes (alcohol and nicotine)

Customs duties

Environmental taxes (eg on energy bills)

Insurance premium tax

Stamp duty

Capital gains tax

Tax on pension lump sums

Inheritance tax

The list is longer than I anticipated, and my first thought is along the lines of: “Wow, I had no idea so much was caught in the tax net.”

VAT is particularly interesting. It's effectively a tax on transactions, allowing the state to take a cut on most dealings between citizens. It doesn't apply to “unprocessed” food stuffs but it is levied on snacks and meals in cafes and restaurants. You might not pay VAT on services from small traders, but you'll pay an extra 20% on getting the roof repaired or replacing a part on your car or bicycle. VAT is even levied on a yoga class I almost booked.

Even this most cursory survey of the British tax system is giving me a fresh perspective; in fact I think I might be entering the second big tax watershed of my life. The first came with the bombing of Iraq. A million or two of us marched in protest, but our taxes still funded the military campaign that killed many civilians and turned out to have been based on a lie. Facing up to this uncomfortable truth catapulted me out of my choir-girl approach to tax. I was forced to recognise that my financial transactions were resourcing violence, destruction and geopolitical games far removed from the interests of ordinary people.

But that was just foreign affairs, I consoled myself. In the early 2000s, reporting on what seemed like a golden age of public service provision under New Labour, I retained some of my faith in the tax system by dint of putting things in separate boxes and not thinking too hard about how they might be connected.

With this, the second major shift in my perception of tax, it's become clear that, unless citizens are extremely vigilant, the natural tendency of those in power is to levy more and more taxes.

The growth and complexity of the modern tax system has set up a situation ripe for the abuse of fiscal power and the exploitation – should we call it taxploitation? – of the public. Below I’ll reference taxes that are clearly being levied or contemplated on a “just because we can” basis, as the authorities think up new ways to take from a trusting public. When taxation works like this, it often has unintended consequences which do lasting damage. The window tax introduced in the seventeenth century, for example, charged property owners by the number of windows, resulting in the bricked-up windows we still see in some older buildings today. Some of the dwellings constructed while the tax was in force were built with the fewest windows possible and contributed to the decline in the health of the urban populations who had to live in them. The tax “on light and air”, as it was known, wasn’t abolished until the mid-nineteenth century.

New/upcoming taxes

In the last few years, a raft of new taxes have been imposed or mooted. The charges for Clean Air Zones (ULEZ, CAZ, LEZ or ZEZ depending where you are) resemble the road tolls of previous times but are actually part of the new order of “environmental taxes” justified on the “polluter pays” principle. The fines which accompany them sit in a strange grey area. They can be very large and cause a lot of distress, see here – and so seem to be part of a punitive system. In any case, they are definitely “revenue-raising”, generating £2.2 million a month for Bristol City Council alone. Kerching!

Then there's pay-per-mile, a new generation tax monster that just keeps on reappearing however much we chase it away. The media often presents this in the context of the government “having to” to make up the loss of revenue it created through tax incentives for electric cars. This is part of the tax inevitability narrative according to which i) citizens must pay more and ii) tax rises are not the government’s fault.

If I had to give A Simple Person's description of these kinds of taxes, I would call them Frightening Taxes. Connected with a system of surveillance and behaviour management aimed at discouraging people from driving, they will, if instituted and enforced, bring an end to the way of life we have spent the last few centuries building in Britain.

Ahead of the Budget on 30th October, the government has been talking of “painful” tax rises. Speculation in the media – whether planted by government sources or not – is of increased capital gains taxes, VAT on private education, council tax changes and measures which would reduce the value of savings and pensions. The mainstream media is full of calculations about how much which prospective tax rise would cost various demographics. But what I find most interesting is what this, the Great Tax Game, says about power and the growing ability of the state to affect our lives.

The increases mooted involve significant sums of money and so would have a material impact on those affected. Capital gains affects those renting out a second property, which happens to be the financial model on which I've built my writing life and my pension plan. Will that model be broken? VAT on private education would oblige some children to change schools suddenly. Quite a lot of people on modest incomes could find themselves in receipt of bills they haven't planned for.

When long held plans can be upended and those of modest means put into financial difficulty at the flick of a chancellor's pen, we're a long way from kratos (rule) by the demos (common people).

VAT on private schooling? Good, I hear some people say: private education is for the privileged and those benefitting from it should pay the price. This leads me to a second significant feature of modern taxation: its hyper-politicisation. When raising tax rates or introducing new taxes, governments tend to use the grievances and preferences of particular interest groups to bolster support for their proposals. Ideological greens can be counted on to support new charges for driving, traditional Labour supporters to back more tax for high earners. Tax becomes a political football, entangled with social mores in which it's considered virtuous to profess willingness to pay a greater share of one’s income “for the NHS”. Tax-naive citizens are easily played off against each other, allowing a canny government to get on with the business of collecting more cash from them while they fight amongst themselves.

Both these aspects of twenty-first century taxation – its ability to dramatically change our lives and the way it exploits social divisions – are all-too apparent in the new generation of behaviour management taxes. It starts small, with a tax on sugar, and before you know it experts are telling you that you'll need to pay the Treasury a fee if you want to eat a cake or bar of chocolate. Why stop at sweet things? Combined with the “we know best” attitude that now characterises Western leaderships, taxation could be used to “nudge” a population into adopting a kind of state-approved healthy diet, as the Institute for Public Policy argues here.

Taxation as behaviour management underpins the idea of carbon taxes. As I've written about before, despite the fact they have no effect on the environment, carbon-based taxes have an enduring appeal to financiers, governments and supra-national organisations interested in monetising our daily lives.

At COP27, former Bank of England adviser Michael Sheren provided an insight into the real reasons for introducing carbon taxes in his enthusiastic talk about “tokenising nature”: making fundamental aspects of the natural world, such as water and trees subject to tax. Finding ways to tax the natural resources of countries such as Indonesia and Brazil is “absolutely critical”, he said, because “we need their natural capital as a system-based world more than we need that 66 billion [gold coins] we’ve got sitting in the basement of the Bank of England.”

This mindset – always looking for more ways of extracting value, of bringing the stuff of life into the fiscal net, is taxation-as-extraction. The nefarious ambitions of Sheren and his like help to explain the expansive momentum of taxation in the West over the past century. Once consent has been given, and the infrastructure put in place to collect and enforce payment, the demands of the tax man will keep on growing and the taxpayers can’t do anything about it.

Can’t they? These days I hear that platitude about the inevitability of taxes with different ears.

It comes, of course, from, Benjamin Franklin, the founding father of the United States in 1789: “Our new Constitution is now established, everything seems to promise it will be durable; but, in this world, nothing is certain except death and taxes.”

It's a political statement, not a description of reality. Once we become tax-savvy and start to see the game of taxation for what it is, or what it has become when corrupted away from its stated purpose of paying for shared services, we start to see that, collectively and individually, we are making choices all the time.

But public spending!

The foregoing is why I keep experiencing high levels of cognitive dissonance when I hear public discourse about tax and spending in the Britain of 2024.

The claims paving the way for the tax hikes of the Budget, whatever they turn out to be, are a case in point. The new Labour government argues that a £22 billion black hole in the public finances created by the last Conservative government necessitates “painful” tax rises.

But even without getting into the sophisticated calculations of the Institute of Fiscal Studies, this claim makes no sense. Firstly, there's the quantitive easing which financed the Covid lockdowns, in an unprecedented level of money printing which illustrated the government’s ability to “find” money when it wanted to.

Then there's Net Zero, a giant environmental tax on the entire nation. Estimates of its global cost by 2050 include “half of global corporate profits and one-quarter of total tax revenue in 2020". The UK's Climate Change Committee guesses that, by the late 2020s, Net Zero will involve spending of around £50 billon a year. The think-tank Civitas published a report which put the cost of making domestic and non-residential properties carbon neutral at £750 billion before, as the Guardian was pleased to report, the study was withdrawn due to “factual errors”. The truth is that no one knows – can possibly know – how much Net Zero - a recent idea - will cost. The government's commitment to this open-ended bill blows any claim that it has costed its spending plans out of the water.

And there's that pledge to provide Ukraine with £3 billion a year “for as long as it takes”. Regardless of the merits of the UK's involvement in that particular conflict, it's another open-ended, costly commitment – and one that represents an overt shift from tax-for-public-services to tax-for-war.

Readers may be thinking of their own examples of potentially reckless or illegitimate public spending; indeed I have one of my own that I'm Not Mentioning Here. The salient point is that in a modern, supposedly democratic society, we the people don't seem to have much say over how much money we hand to the state or how that money is spent.

The fact that British tax revenues are at their highest since the period following World War II is hardly reassuring. It gives me another fiscal problem which could be formulated as the question: Where is all the money going?

For context, it seems important to point out that it is not unknown for an advanced Western democracy to have large amounts of public money unaccounted for. The federal government of the United States is unable to account for trillions of dollars. The missing tax dollars represent more than an accounting failure: eye-watering sums are being spent on unknown activities, raising the question of what behind-the-scenes activities American taxpayers are unwittingly funding.

Meanwhile, British taxpayers are getting less and less of what they pay for. The woman on the radio phone-in I referred to earlier was speaking in the context of Birmingham City Council's financial difficulties. Having gone (technically) bankrupt, Birmingham plans to raise council tax by 21% over the next two years while making huge cuts to services. Bin collections will go fortnightly, libraries will close and road maintenance will be further reduced. Arts institutions in the city, which is home to the Birmingham Symphony Orchestra and Birmingham Royal Ballet, will lose all their funding.

Where IS all the money going?

Losing my fiscal innocence

A counterpoint to the sad-bottomless-pit-of-a-taxpayer of the radio phone-in comes from the street where I live. One Sunday afternoon, I passed a young woman picking up litter. I was impressed that someone who should properly have been nursing a hangover or spending time with a lover was doing the council's job – a council which had defunded the well-used local library and wouldn't pay for any Christmas lights. In conversation with the young woman, I wondered aloud what we were paying council tax for. She agreed wholeheartedly and somehow the phrase “tax strike” passed between us.

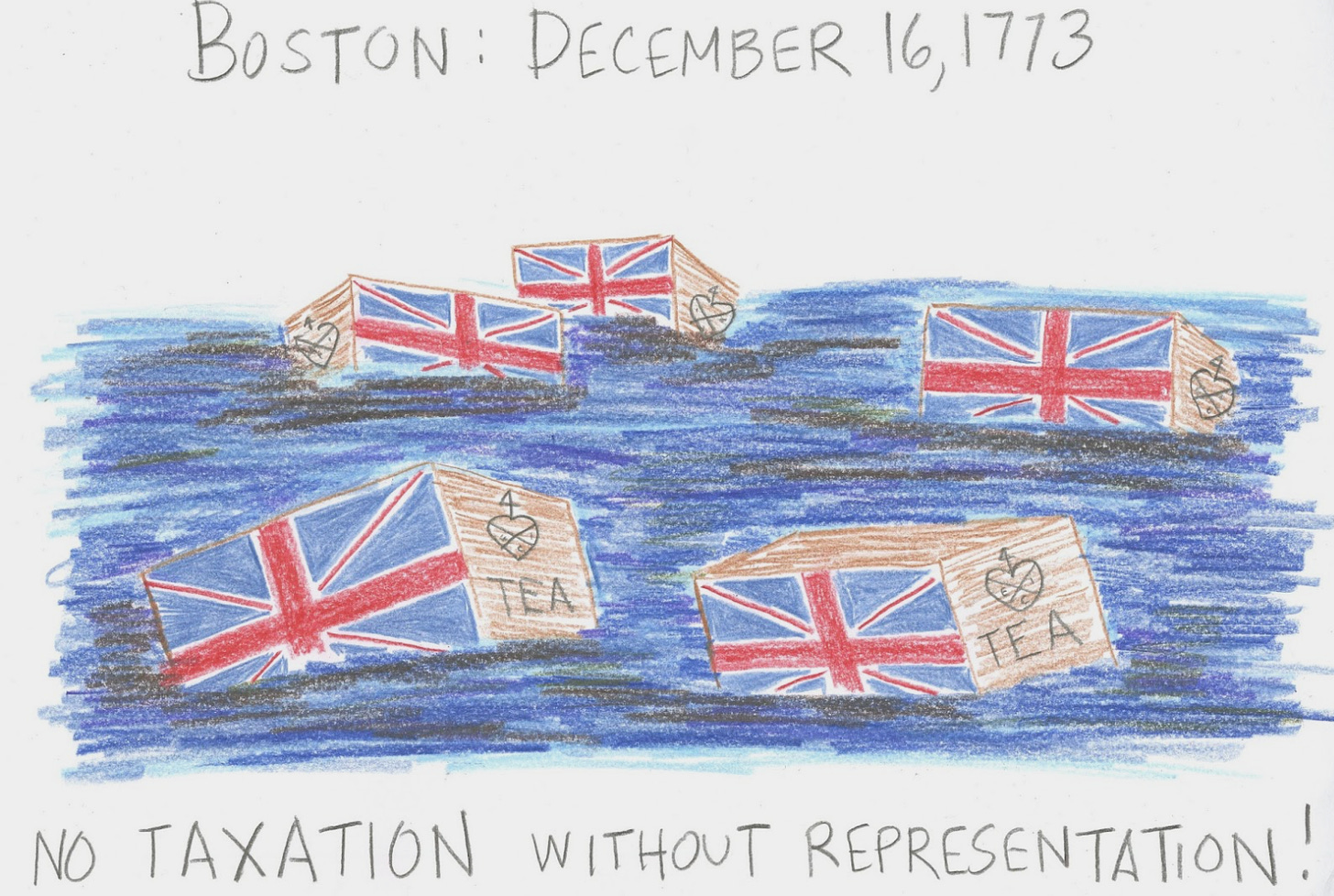

I think of this as my Boston Tea Party moment. Refusing to pay tax is a thought I never would have entertained pre-2020, nor would I have expected it from a young person public-spirited enough to pick litter. But these days I know people who refuse to pay into a system they regard as systemically corrupt. They're prepared to deal with endless correspondence, court orders and bailiffs in order to uphold a principle, a principle that is the fiscal equivalent of democratic responsibility. And I get it.

Because somehow, we seem to have got ourselves into a big fiscal mess. We face endless demands for money on all aspects of life and we're expected to put up with failing infrastructure and fewer services. There's little transparency about what our money is spent on and no accountability except via periodic elections offering only choice between slight shifts in emphasis and breakable manifesto promises.

The big spenders won't give up their pet projects and tax-based ability to control our lives of their own accord. It's up to us, the funders, to take responsibility for the money we hand over, just as voters we are ultimately responsible for the government we elect.

So, in the interests of promoting greater tax literacy, here are a few starter questions:

Are taxes consistent with the role of the state in a democracy?

What areas of national life needed to be funded by taxation? What do not?

Do the taxes in place have the genuine consent of most people?

What mechanisms are in place to ensure transparency and accountability in spending?

I'm no longer prepared to extend my choir-girl trust to national figureheads. I've lost my fiscal innocence and I want answers.

AUTHOR'S UPDATE: I regret to note that, following the Budget, the UK now has its highest levels of tax ever, exceeding even those during and following World War II.

Tax was never destined to properly serve the collective-pot-for-shared-services ethos. To the extent that it does, it's accidental. This is because, as you point out, taxes were born in iniquity (war) and things have only got worse. Tax is also intimately linked to the banking / money creation fraud. The government raises debt to fund expenditure that goes to the corporatocracy - think £37bn for track and trace and God knows how many billions on 'vaccines'. The interest on that debt then goes to banks and is paid for by the taxpayer so it's a double whammy.

Tax is ultimately an efficient means of wealth transfer from the poor to the rich. And remember the rich, including multinational corporates, don't pay tax or, if they do, it's a token amount. Tax is the means by which we pay for our demise.

The tax strike would be a way forward...but united we stand and divided we fall. Even if you could get enough people on board, how do you tell an employer not to deduct PAYE? The bastards have put up a very effective barrier to a tax strike by collecting at source - essentially not giving you a choice. Which is exactly what you'd do if you knew that the money you were taking was not going to be used for the purpose taxpayers want it to be used.

Let's face it, 95% of tax really is just theft.