TaxNation

We need to talk about tax

For many of us, it seemed that every time we looked up during the run-up to this year’s Budget there were new threats on the horizon. The kite flying started in August, with endless suggestions of new or higher taxes floated in the media. By the time we got to November, economics expert Liam Halligan was condemning “the most chaotic, counter-productive run-up” to a Budget he’d ever witnessed.

Some taxes had never been contemplated in mainstream Britain before (a “tourist tax”). Some were ridiculous (a “milkshake tax”). And some were potentially upending – taxes that risk breaking business models and overturning decades of financial planning for certain groups and individuals. My YouTube feed has been full of videos advising people to LEAVE THE UK NOW (an “exit tax”) and WhatsApp groups of speculation about new property taxes. The kite flying was an amplified re-run up to last year’s Budget which resulted in inheritance tax changes that will put an estimated two in five farms out of business.

None of this is normal. You can’t have a stable society when lives can be upended at the stroke of a Chancellor’s pen. Britain’s fiscal unpredictability creates constant low level anxiety and stalls decision-making at all levels. Like many others, I can no longer afford to move because of the rises in stamp duty and capital gains tax announced in last year’s Budget. This year, the Chancellor made clear she had no scruples in breaking the manifesto promise not to raise income tax, National Insurance or VAT. All this raises questions of legitimacy. In a genuine democracy, taxation has to have a broad basis of consent, otherwise it becomes regarded as a type of extortion which the majority only pay on threat of imprisonment.

Taxes in the UK are the highest they’ve ever been and, unless there’s a change of course, set to keep rising. Old taxes keep going up and new taxes are being introduced for purposes other than revenue-raising.

This dysfunctional situation is symptomatic of where we are in Britain 2025 and the issues that need to be addressed if we’re going to make it through the next few years with our health, freedoms and finances intact.

We really need to talk about tax.

I’ll get to the Budget – including some shocking information about how the government is using our own money to prep us for tax rises – later. But first, we need to consider some of the broader, less-seen issues around tax.

Tax taboos

Here’s the paradox: while tax is a very emotive subject, mainstream discourse about it tends to exclude emotions. Politicians, experts and journalists talk in economic abstractions: the need to “balance the budget”, the effects of taxes on “growth”, “economic activity” and “the housing market”. This abstract language tends to minimise the human consequences of tax changes and, when it does acknowledge them, reduce them to the effects on particular demographics such as “pensioners”.

It also ignores the foundational questions about taxation: what it sets out to achieve and what happens when public money is used for things for which there’s no real consent. Like Adam Smith’s “invisible hand”, tax is treated as an external phenomenon over which we have no control, at least not between elections. Look deeper and the operating assumption comes into view: government collects taxes for our benefit and even when acting with manifest incompetence, is working in the public interest. This assumption generates many of the emotional responses we now see in the public sphere: if only government would listen, if only we could explain well enough, things could be remedied. At the same time, it forestalls a hard look at reality and the possibility that – something that has played out in history many times – the tax system is furthering interests that are not ours.

Questioning the established narrative about tax arouses buried fears about what might happen if the status quo is disrupted, making people avoidant or angry. So most stay safely within the established terms, arguing amongst themselves about which taxes should be raised and thinking up new ways to help the Treasury. The debate about pay-per-mile, which I suggested in a previous piece is a tax for which consent is being manufactured via think tanks, is a classic example. Pay-per-mile is somehow inevitable, the story goes, because the government “must” replace the income it loses through fuel duties as more people drive electric cars. Putting aside doubts about the nation going fully electric any time soon, it’s a view which assumes the only option is the creation of a complex new track-and-charge system.

The Black Hole Narrative draws people in, offering a neat figure which “proves” that taxes must rise. Its success relies on us failing to notice how the government seems able to come up with the money to fund projects it likes and ignoring the fact that it IS possible to change spending commitments. See my personal stab at spending cuts at the end of this piece.

Talk about tax in Britain is highly politicised and tribal: it often sounds like the children of autocratic parents fighting amongst themselves. Participants call for their brothers and sisters to be deprived of pocket money, trips or presents because something is “not fair” or because they feel a sibling must be punished. In the Left/Right tax wars, the two main sides have their own lobbying organisations: the TaxPayer’s Alliance and the Tax Justice Network.

Add to that the low public understanding of tax and we’re in a vulnerable position. Some people believe they “don’t pay tax” by virtue of being below the threshold for income tax. In fact, we pay tax on almost everything – on goods and services, on energy and fuel, on insurance and apprenticeships, to name but few. Often there are several layers of tax: a meal in a cafe may carry VAT and include the energy levies. The price of supposed “tax-free” foods includes taxes on farming and transport. The lack of transparency means that the average member of the public just thinks “prices have gone up”.

In our current situation, our tax illiteracy means that we – or at least our standard of living and assets – are there for the taking.

The Tax Contract

The “tax contract”, unlike the social contract, isn’t a recognised concept in political theory. I use the phrase to refer to the underlying consent of the public which, in a democracy, gives taxation its legitimacy. The metaphorical presence of the tax contract is arguably even less demonstrable than its governance sibling which is backed by constitution and laws. Nonetheless, the tax contract IS essential. Governments know when the people consider it broken: witness the Peasants’ Revolt, the Boston Tea Party and the poll tax riots.

Like the frog in the water brought imperceptibly to the boil, the tax contract can be broken gradually. In Britain we’ve entered a phase in which the legitimacy of tax is being questioned quite widely. Recently I struck up conversation with a young woman picking litter up in my street and before we knew it, the words “council” and “tax strike” had passed between us. In Epping, some residents are withholding council tax until the council stops using a local hotel to house migrants.

Anti-tax sentiments arise out of a sense of mis-spending or unfairness. But to really understand the fiscal rights and wrongs and get clear about what we want as a society, we need to consider some deeper issues. The first has to do with the phenomenon of ever-rising taxes.

In modern history, taxes generally go one way: UP. Income tax was introduced as a temporary tax to fund war but somehow was never cancelled, becoming routine for British workers mid-twentieth century. Capital Gains was introduced in 1965. VAT was invented in 1973 at a rate of 10%. The standard explanation for the upward direction of taxes lies with complexity of modern life: the state does more and so requires more resources. But take a step back and you could equally envisage the opposite scenario: once the basic infrastructure is set up, efficient maintenance and technological developments could make things cheaper. The Severn Bridge is now free after decades of tolls paid off the initial build. The Victorians built many public facilities through “subscription”.

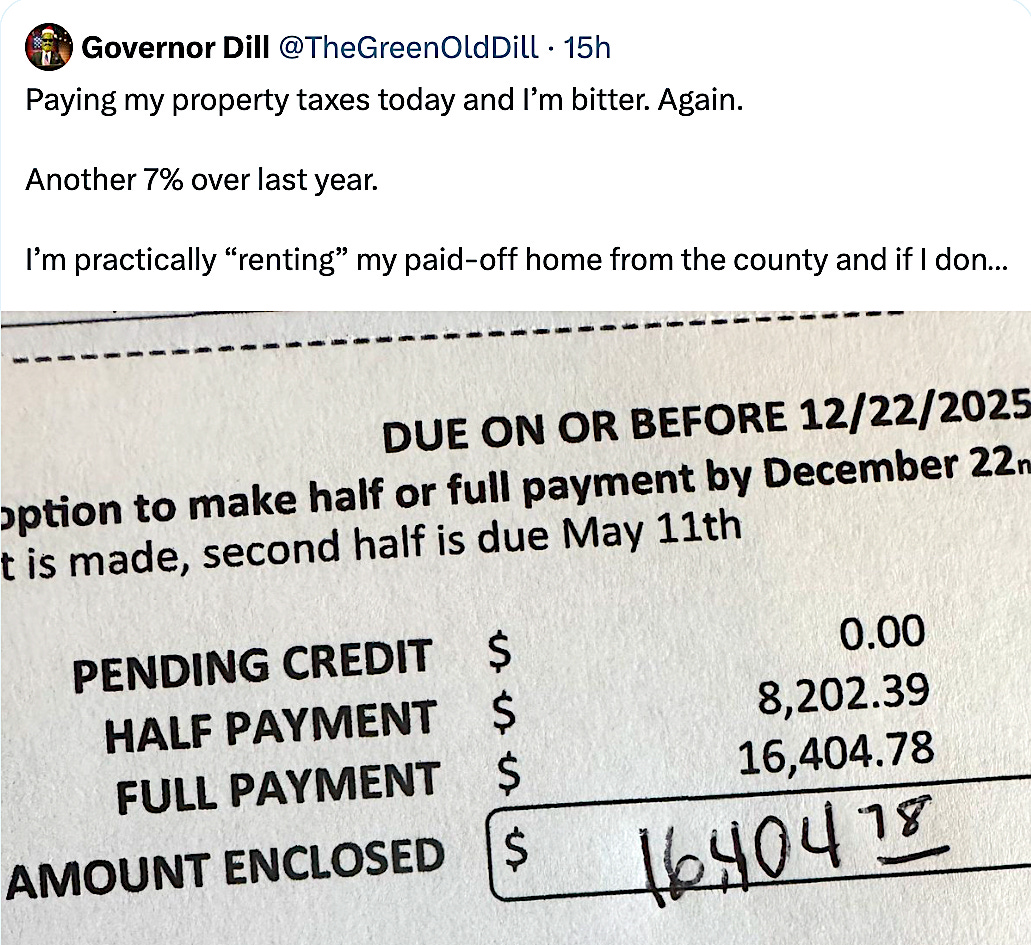

In contrast, the tax burden is now the highest in the UK’s history. While some taxes may not have gone up officially, they’ve still increased thanks to fiscal drag. The threshold for income tax was frozen in 2022 and as a result we pay a greater proportion of our income in tax, raising an estimated £43 billion for the Treasury by 2028. The threshold for inheritance tax has been £325,000 since 2009, a freeze which has brought more estates into the tax bracket.

Some taxes are really hidden. I’ve been trying for years to get a clear understanding of what proportion of our energy bills – some of the highest in the world – goes to government. New stealth taxes add to the cost of owning a car: clean air schemes and fines generate considerable amounts for council coffers, while residents can pay up to £1073 for an annual permit in a controlled parking zone. Essentially, the council has monetised the street by turning it into a car park.

Here’s a new tax you may never see. In 2027, the UK government will follow the EU in introducing the world’s first carbon border tax. The Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism will levy a fee on imports of goods deemed to be “carbon-intensive” such as fertiliser, comment, iron and steel. Which goods and services do you think will go up as a result?

When people fail to notice the creep-creep of rising taxes, a sudden realisation can bring about a change in behaviour. A commercially successful writer I know has cancelled a lucrative series of books because she felt she was writing seven days a week for the government. A tradesman I hoped to hire never quoted after telling me he might go back to Poland because, after tax, he earns less than his workmen.

How you think about taxation – what it is for – affects your perception of whether and at what point the tax contract is broken. In this article, Brett Scott outlines five conceptual models for the purpose of tax. The first is the libertarian or classical liberal idea of the state taking money from freely transacting individuals, expressed in its most extreme form as “tax as theft”. The second model conceives of tax as fees to pay for public infrastructure and services. The third, drawing on ideas of social justice, sees tax as a way of bringing about a “justified redistribution” of wealth. The fourth is a technocratic view which uses tax as a “strategic instrument” to incentivise behaviour the state considers desirable and ultimately to reshape society. (The fifth model raises some interesting questions beyond the scope of this Substack.)

It’s fun to think about where you are on this spectrum. As I described in my Budget-inspired piece last year, I used to think of tax in terms of the second model, as a necessary contribution to the public pot. But recent years have brought about an attitudinal shift. It illustrates a point not covered by Scott which has to do with trustworthiness: how far tax spenders are fulfilling the stated purposes of the taxes they take. I might never have questioned Model no 2 if I’d remained convinced that, on the whole, taxes were spent on services and infrastructure. But now it seems that a significant proportion is funding politicians’ pet projects, crony contracts and technocratic experiments, I now tend towards Model no 1.

In other words, the legitimacy of taxation depends on two things rarely mentioned in this context: trust and relationship. If people don’t trust that their money is being spent wisely and if the relationship with government has broken down, the writing is on the wall for the tax contract. In no other area of life is your financial support unconditional and infinite. If your spouse was misusing shared finances, if you couldn’t see what your business partner was up to, or if your adult child kept stinging you to fund a drug or gambling habit, sooner or later you’d put a stop to it.

Our tax blindness is disabling. With little clarity about the purposes of tax, we have no means to ascertain whether public money is being used well. Avoidance of “boring talk about money” prevents us from seeing the political uses of our taxes, even when the social engineering and vested interests are blatant.

In matters of tax, as so much else, the first step to change is seeing.

The MORE TAX! lobby

The MORE TAX! lobby is a central player in Britain’s mainstream narrative about tax. It’s obvious example of Model 3 (tax as justified redistribution) and Model 4 (tax to change behaviour and reshape society). More tax advocates tend to get excited about the prospect of more taxes, especially for groups they consider deserving of punishment, and their communications often have an ideological fervour.

More significantly, there’s a growing body of evidence to suggest the MORE TAX! lobby is being organised and funded by a wider, extra-democratic set of interests.

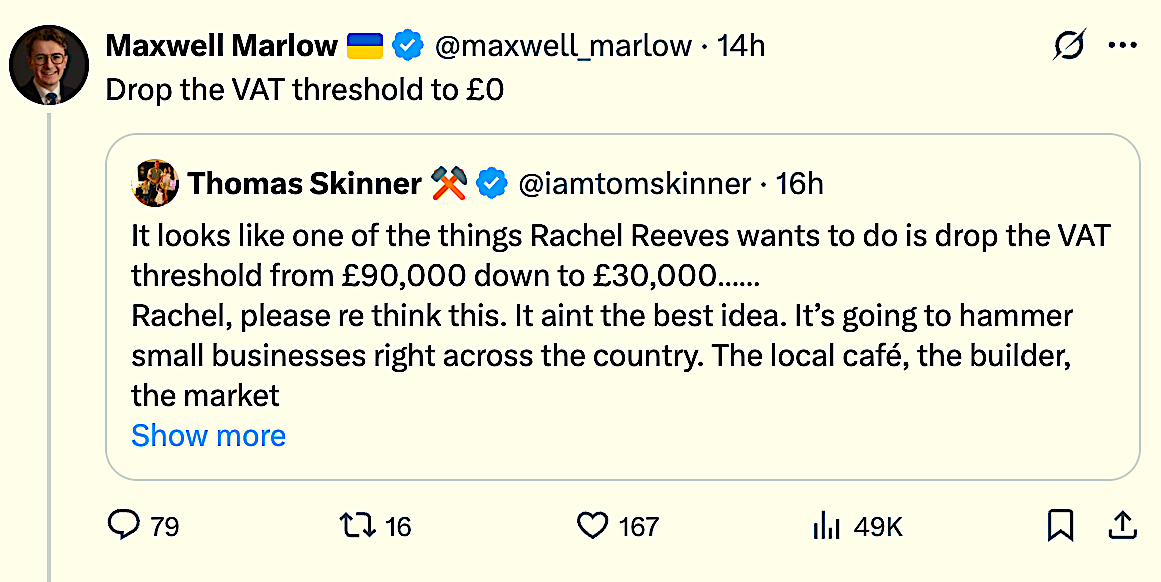

The story of CenTax is illustrative. It’s a prime example of the trend in which think tanks – traditionally focused on public benefit and (somewhat) independent – have taken to lobbying for higher taxes, right down to doing the sums and suggesting ways government can overcome public opposition to unpopular measures. For months, the Resolution Foundation has been steadily planting ideas in the media: the VAT threshold should be reduced to £30,000, there should be carbon levies on long haul flights and income tax should be raised by 2 pence.

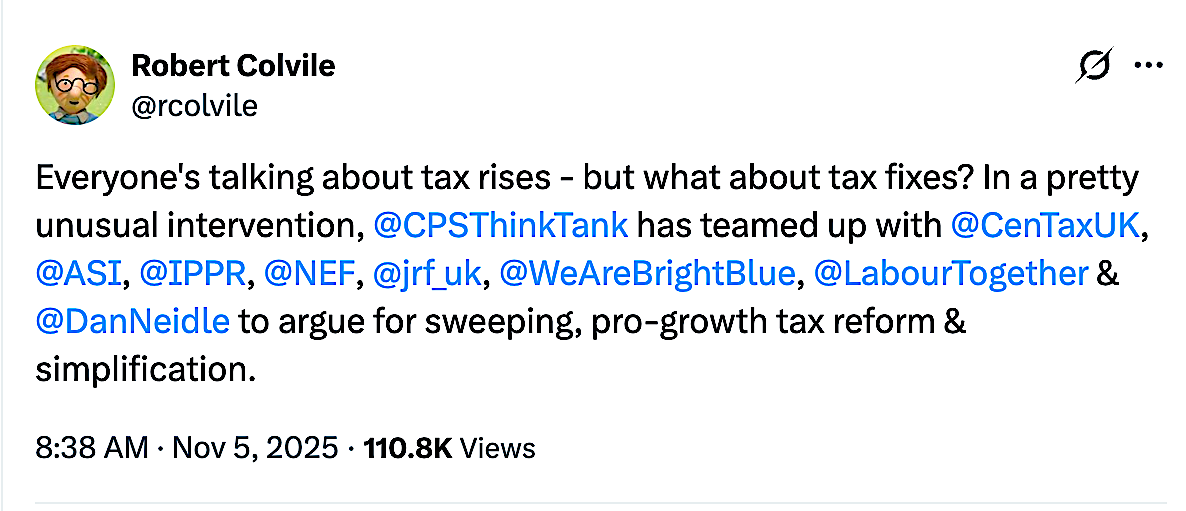

Then, a couple of weeks before the Budget, a group of think tanks published a report proposing a suite of tax reforms which included some of the more controversial ideas floated over recent months.

The accompanying publicity made much of the “rare alliance” of “think tanks from across the political spectrum” which included the Centre for Policy Studies, Institute for Public Policy Research, Adam Smith Institute, New Economics Foundation and Joseph Rowntree Foundation. According to the press release “Unlikely allies unite on tax reform to rescue Britain’s stalled economy”, the coalition had cracked a thorny problem, producing a set of taxes that would promote economic growth and create more fairness, all without increasing the tax burden.

How miraculous - amid all the confusion and anxiety, a saviour in the form of an expert consensus presenting a painless solution!

A deeper look reveals that something strange is afoot. The Centre for the Analysis of Taxation was founded a little over a year ago, a couple of months after Labour came to power. With a grant of £1,326,980 from UKRI, another £999,945 from the ESRC and a donation of £84,912 from HMRC, the organisation’s biggest funder is the taxpayer. The new think tank has no office and receives “in kind support” from the two universities who also pay its directors. It does, on the other hand, have quite a large staff with research and communications skills.

It’s impossible to avoid the question: was CenTax set up specifically for the purpose of promoting a radical tax reform agenda that ultimately comes from government?

Before considering this possibility further, let’s take a look at the changes proposed in CenTax’s timely report. Tax Reforms for Growth is very brief and makes its case in the most general terms. I’ve picked things that strike me as significant, so the following list is not comprehensive.

New property taxes to replace stamp duty based on regular property revaluations

The rate of VAT to be lowered but its scope to be widened. Lower income groups to be “compensated” for the higher cost of basic goods

Landlords to be charged National Insurance

Capital gains tax to be added to inheritance tax

An “exit tax” to be levied on the wealth of those leaving the UK

Each proposal ends with a sentence about adjustments to make it “revenue neutral”. But the proposals themselves suggest the opposite: CGT on top of inheritance tax would obviously increase death duties. An exit tax would be in addition to the income, VAT, corporation and (realised) capital gains tax already paid by the emigrant. National insurance on income from rental property would generate more revenue for the Treasury.

Let me repeat: CenTax has received support from HMRC.

The VAT proposal is more opaque: the suggestion seems to be it should be applied to food and other basics, with the resulting inflationary jump offset by benefits for the poorest. Property taxes based on regular revaluation would be a more reliable source of income than property sales which have slumped following the rises in stamp duty. Such changes would bring about a structural shift in which government would have more power to pull in revenue and citizens less room to manoeuvre. New taxes might be brought in on the promise they would be “revenue neutral”, but rates could easily be raised to fill the latest black hole.

Meanwhile, the human consequences would be considerable: the cost of owning a property would go up, and the homeowner be liable for rises in values even if they had no plans to sell. More of those inheriting property would have to sell up to pay the taxman. An exit tax would curtail people’s ability to start a new life elsewhere and keep some in the UK unwillingly. Rents would go up. The expansion of VAT would raise the cost of food and other basics, and the need for “compensation” make more dependent on state benefits.

Recalling CenTax’s sudden appearance, it looks very much as if a circular policy economy has been set up, whereby the government funds third parties to create the impression that independent experts support for controversial policies. The approach resembles that used by the cycling charity Sustrans, which has received huge amounts of public money to lobby regional governments for policies the government wanted in the first place - resulting in contracts for Sustrans.

With respect to HMRC, the circle is very small: HMRC has donated resources to a project aiming to get HMRC more revenues.

So there we have it: the mechanisms of manufacturing consent and circumventing democracy with a fiscal application. But are they also serving another purpose?

One of the most notable aspects of CenTax’s proposals is their effect on property ownership. They would likely make it more expensive and, by extension, push up the price of rents. This is of a piece with many other recent measures: tax changes and new regulations that have caused many landlords to sell up, double council tax on second homes, and dramatic rises in stamp duty and capital gains.

Then there’s the farmland.

This may go some way to explain the presence of Abrdn Financial Fairness Trust on the list of CenTax’s funders - £674,200 since the think tank was founded in September 2024. The Trust, the charitable branch of one of the UK’s biggest land owners, has form in funding work that recommends new taxes on land ownership. In July 2024, the think tank Demos published The Future of Inheritance Tax in Britain, a report which recommended the exclusion of farms from inheritance tax should be lifted. The report was sponsored by the Aberdeen Group who, as David Craig points out in this article, identified farms as an obstacle to land being acquired by “purely financial owners” in a 2018 report. The abrdn Financial Fairness Trust is also a regular donor to Demos’ general funds.

Three months after the Demos report, the Chancellor announced that farms valued at over £1 million would be subject to inheritance tax. The decision made little sense in terms of “balancing the budget”, since the amount the Treasury estimated it would raise – £520 million a year – is small, and less than the amount the UK government is giving in aid to foreign farmers. So what is the purpose of the tax?

Amid the ensuing furore, Treasury ministers claimed that “tax and economics experts” considered the tax on farms “reasonable and fair”. It turned out that the “experts” were CenTax director Arun Advani who also sits on the board of the Office for Budget Responsibility. Reporting this, Guido Fawkes commented: “Advani said at Labour Conference that he was “optimistic” because the Labour government is “genuinely listening” to his ideas. The groundswell of support for Labour’s tax hikes is being entirely manufactured.”

There’s more. In a CenTax report published in October 2024, Advani argued that the cap for Agricultural and Business relief for farms should be set at £500,000. That would oblige many farmers to sell up so, in order to prevent a drop in national food production, he recommended “the state taking part-ownership of land and becoming the landlord to tenant farmers”.

State expropriation of farmland is not new. In the early twentieth century, Albania was a largely agricultural society, with much of the population working small family farms. After taking power in 1944, communist dictator Enver Hoxha set about removing farms from private ownership through a series of agrarian reforms and ruinous taxes. Over time, independent family farms were eliminated and agricultural workers became dependent on the state.

Prior to the collectivisation of agriculture, Albania had been largely self-sufficient in food. In the 1980s, food was so short that rationing was introduced and, by the time the regime collapsed in the early 1990s, even basics such as flour were in short supply. International food aid was needed to save the population from starvation.

How easy it is to advocate sweeping changes when the consequences are not real to you! A lot of the talk about tax reminds me of conversations about Society I used to have as a teenager. I can only assume this is the spirit in which Guardian columnist Zoe Williams casually suggests that the inheritance tax rate should be 100% – a euphemism for the state requisitioning of assets.

The Budget

I wrote the foregoing before the Budget. In the event, what we got included:

income tax allowances frozen until 2031 – a de factor tax rises for most people

landlords to pay extra income tax – so rents will rise

a council tax surcharge on properties over £2 million (the beginning of new property taxes?)

pay-per-mile on electric vehicles (opening the way for a universal track-and-pay system)

VAT on taxis (making safe travel more costly for women at night)

a tourist tax (more powers to mayors)

tax on milkshakes (no words)

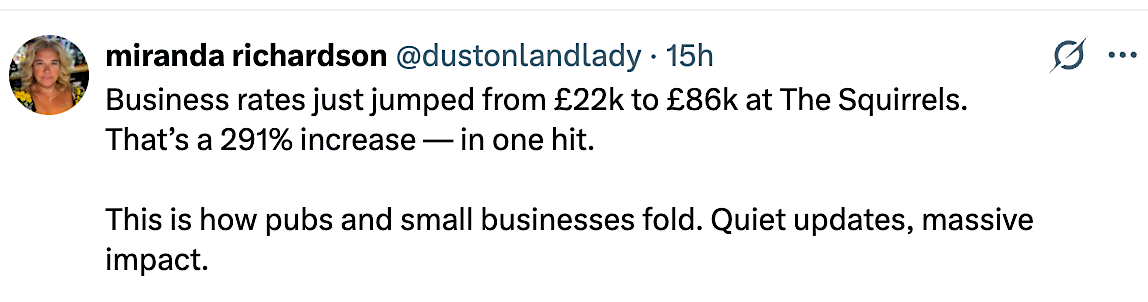

And there’s something very complicated going on with business rates. It seems a combination of revaluations and other reforms are hugely increasing costs for the hospitality industry. Expect more cafes and pubs closing in 2026.

Right, now let’s do something fun.

Let’s Play Chancellor!

This versatile game can be played with two or more players, but also alone.

Assume a £22 billion “black hole”. What cuts would you make?

Alex would cut …

Funding for Artificial Intelligence

The government has gone AI-mad, instituting the creation of many new data centres and legislation enabling AI to be used for decision-making in public services and the UK is already the world’s third-largest nation for data centres. The government has invested £2 billion in an investment package designed to accelerate the use of AI - but that’s just the tip of the iceberg. According to the UK AI Public Sector Procurement Tracker, 2025 has been a record year, with contracts awarded for all many of public bodies, from the Met to the BBC.

My reasoning: as a nation, we clearly don’t know what we’re doing. AI data centres require huge amounts of power and water. Our water infrastructure is failing and according to NESO, energy rationing for households and businesses is on the way. Some of the planned AI applications, such as automated decision-making in healthcare and facial recognition to predict crime, are highly concerning. And the relationship between the AI sector and government is far from clean: in just three months, Tech Minister Peter Kyle had thirty meetings with AI bosses.

Let’s just pause until we’ve had a bit of a think.

Saving: at least £2 billion

Net Zero

According to the Office for Budget Responsibility and the Climate Change Committee, the cost of Net Zero to the taxpayer will be around £4 billion a year until 2050.

This is quite a lot, given how much trouble Net Zero is causing: with the transition to “clean energy” bringing rationing at peak hours, we won’t have the power to cook supper or charge our electric bicycles. The estimated £4 billion is undoubtedly conservative: the truth is that no one knows how much Net Zero will cost. And the figure doesn’t take into account the cost to citizens in heat pumps and whatnot.

Saving: £4 billion a year

Military aid for Ukraine

I can’t argue for or against supporting Ukraine in the conflict with Russia but that is part of my reasoning: I just don’t know enough about it. My background in Middle Eastern affairs strongly suggests two things are likely to be true: the conflict is infinitely more complex than outsiders imagine, with deep historical roots, and geopolitical interests are trying to shape the outcome in ways that are not visible to the public.

More generally, war is extremely lucrative. As a graffiti artist in Lisbon put it: War Is State Business. And I’ll say this bit out loud: we don’t really know where all the money is going.

In any case, pledging indefinite financial support for a conflict just isn’t on. See: Vietnam.

Saving: £3 billion a year

UK Research and Innovation

This is taxpayer-funded research institute has a budget of nearly £9 billion for the current financial year. I’m showing clemency and only slashing their budget by half as I assume UKRI does fund some work of benefit to humanity. Spending £10 million on “modelling” the effects of dimming the sun does not enter this category.

As a quango operating independently from government but funded by the Department for Science, Innovation and Technology, UKRI provides ministers with the perfect means to conduct controversial projects while saying “it’s nothing to do with us”. This is how Climate Minister Kerry McCarthy played it during the parliamentary debate on geoengineering when MPs questioned the wisdom of the Advanced Research and Innovation Agency, another arms-length body spending £57 million of taxpayer’s money on sun-dimming experiments.

I’m axing ARIA, which is getting £211 million from DSIT in the current financial year, completely. We need sunlight, otherwise we die.

Saving: £5 billion

The total, while kindly conservative, is only £14 billion – not enough.

You can perhaps see my strategy. For the purposes of the game, I’ve chosen initiatives or organisations with identifiable costs rather than suggesting cuts to, say, the civil service, welfare budgets or other parts of the public sector.

The rationale for my approach involves cuts to innovation, especially those with costs likely to spiral out of control. Britain needs to get back to basics. A fully functioning water supply would be a start – the streets in my area course with water leaking from Victorian pipes as the Thames Water fiasco continues without any sign of resolution. Developed countries tend to have a system of primary healthcare where you can see a doctor or a dentist if you need to. Call me old fashioned, but I think we should get these things sorted before financing a technocratic dystopia.

For this reason, I’m also scrapping:

The NHS Plan

The Plan, which I examined in this Substack, is extraordinarily ambitious and expensive. It involves “three radical shifts” to create a “reimagined NHS”: the creation of neighbourhood health services, the digitalisation of services, and a host of hi-tech measures around preventative healthcare. These include the use of data, genomics and AI to create personalised care plans which will prescribe innovative vaccines and other interventions at scale. Wearables are to become standard, providing a constant flow of information about patients through biosensors, smart fabric and nanotechnology in home and workplace.

The whopping £29 billion the government has allocated is probably just the first step, funding to explore partnerships with technology, biotech and pharmaceutical companies. It’s even more than the extra revenue the Office for Budget Responsibility predicts that Budget 2025 will generate a year. I think I’ve won!

Another version of the game “What’s in a taxpayer’s’ billion?” would deal in mere millions. In that case, I’d scrap the Climate Change Committee – see what I’ve got against them here - which has an annual budget of around £3.7 million, and Active Travel which has been funding roadblock misery up and down the land. This version of the game offers great potential for examining spending by your local council. And The Procurement Files on X is a constant source of weird and wonderful things the British taxpayer is funding.

Advisory note: do not play this game at Christmas unless you have got to the point where you are so bored that an argument would be welcome.

Substack & author update

Thanks very much to new subscribers for signing up. New pieces are generally published once a month. The relative infrequency is largely because many of my pieces are long and research-intensive and also because I recognise inboxes are flooded with “information”.

Here are a few short media articles I wrote during 2025 which relate to topics covered in this Substack:

What the collapse of Lebanon’s national grid call teach us in Britain – how would we cope with ongoing rationing?

An afternoon observing the construction of a solar farm in my native Gloucestershire

With councils ignoring locals’ wishes and basic rights, is it time for formal curbs on their powers?

I’ve been an interview guest on British Thought Leaders, talking about digital ID and Ofcom’s plans to impose more restrictions on the internet.

In the run-up to Christmas, I’d like to do an unapologetic plug for my short book about Albania. Originally conceived as part of a full-length book about European cities that was kiboshed by Covid, it found expression as a “midform” publication – a train journey length read that’s longer than an article but shorter than a book.

The material was just too good to trash. The story of Albania is fascinating, both in its own right and as a mirror for our times. There are echoes of the Hoxha regime in the censorship and increased state control we’re now seeing, along with – an under-documented aspect of authoritarianism – the sheer, almost comedic, absurdity of many current ideologies. The forms of tyranny may change, but the core elements, at least until humanity evolves beyond the need-to-control, remain the same. A traveller’s tale combining narrative with journalistic interviews, Spyless in Tirana would make a good stocking filler.

If you’re open to a recommendation of a remarkably prescient work of fiction, the precision of That Hideous Strength by C S Lewis makes Brave New World and Animal Farm look generic. The final in a sci-fi trilogy, the 1945 novel chronicles the attempts by a group of globalist technocrats to take over a town in the heart of England. Under the leadership of a mysterious Arthurian figure, a very English Resistance (and a bear) rallies to save the soul of humanity. If you’re up for some off-planet imaginings, the trilogy is well worth reading in its entirety and provides some context for our earthly travails that I tend not to talk about. In 2026 I’ll be writing a Substack about Lewis’s contribution to dystopian fiction.

In February, I’ll be speaking at the Carnival of Alternative Politics in Bournemouth.

The next Substack - the post for January - is on a subject I’ve been cogitating since 2021: non-compliance. For ease of reading, it will published in that quiet interregnum between Christmas and New Year.

AUTHOR UPDATE:

It is now being widely reported that, according to the Office for Budget Responsibility, the "black hole" which was the basis for this Budget never existed.

I find it hard to get my head around tax, as I have lived a life where I have never had to think about it much - bizarre though that is! I guess it is also deliberately set up to confuse and be deadly boring.

So interesting that many taxes we 'take for granted' have not been around for very long.

Looking forward to your thoughts on non-compliance.

I find myself recommending 'That Hideous Strength' a lot these days! Particularly around how easy it is to suck someone into helping further humanity's demise through flattery and playing on insecurities and the desire to belong to the in-group. The former mayor of my city springs to mind, amongst many others.