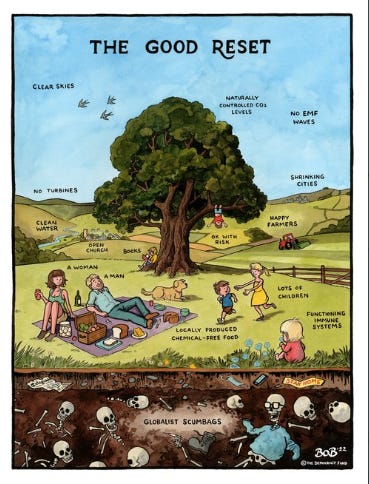

The Year of The Good Reset

A short piece on ways of responding to the challenges of 2023

How would you like the coming year to be? And the one after that? Those in a decade? And further into the future, even if you’re no longer here, life for the people who come after you?

These are the questions of our times.

Author of the Great Citizens’ Declaration Michaela Schippers has formulated a specific set of questions to use as brainstorming tools:

what would the ideal future look like if there were no constraints?

what would the future of the world look like if we go on like this?

what can I do to make a difference?

A psychology professor at Erasmus University, Schippers suggests we write our own ‘letter to the future’ as a way of opening up our thinking. We may want to rephrase the questions to reflect our own way of seeing. My current formulation, for example, is: ‘what would promote human flourishing?’ Or, perhaps, drawing on one of the oldest and most open of philosophical questions: what would make for the good life?

While the emphasis of such questions may vary, the common element is the need to go back to basics of human life. This need to ask fundamental questions acquired a new urgency in the year-just-gone. It’s a healthy response to the times, with their dramatic and disorienting changes, the vanishing of old certainties and the appearance of new things that don’t make sense. It stems from a deep concern that we are heading in the wrong direction.

This wrong future is being given many labels. Fascism. Socialism. Communism. As someone who’s taught political theory and been involved in politics of one kind or another most of my life, I’m both amused and appalled by the inaccuracy of the descriptions. As a writer and educator, I’d really, really like it if people would use apostrophes correctly and listen politely to alternative points of view. But that’s not happening, and it’s understandable: people are reacting with fear and anger to a fast-moving threat which is both old and new.

Identifying the old part is relatively easy: it’s the age-old threat of tyranny and the tendency of a small group to dominate, by commandeering power and resources, the majority. It’s the story of most civilisations and almost all political (and some religious) systems before the arrival of liberal democracy.

Identifying the twenty-first century form of tyranny is harder because its main features only developed in recent decades. And they’ve taken us unawares, emerging at a time when most of us in the west thought that tyranny was a thing of the textbook past and believed that the changes going on around us were only for our good. But the shadow side of progress is now emerging and coalescing into a new form of domination composed of technology and global forces. It serves both commercial interests and the state, along with a range of actors and organisations poised to benefit from both. It’s neither of the left or the right, nor has it any historical precedent. So, for now, let’s call it Big Power.

The emergence of Big Power in the Covid crisis and the ongoing playing out of its agenda through legislation for future pandemics, plans for digital ID and CBDCs, carbon rationing and AI, has brought humanity to a fork in the road. Will we continue down the path of top-down government where life-changing decisions are made on our behalf?

‘In that sense 2020 can be seen as a turning point in history,’ writes Schippers. ‘Co-occurring with the current crisis is a progressive ideology of a small group of people, who see the crisis as an opportunity to alter the course of history and establish their utopia. However, the question is if this is a utopia that is good for humankind, or only for a small group of people. Generally speaking, top down “one size fits all” decisions are detrimental to people’s mental well-being.’

The word ‘crisis’ comes from the Greek, meaning a turning point, a decisive moment, a critical junction. We have arrived at a moment of choice.

So, with 2023 beginning a phase likely to determine the nature of life for the next few generations, how should we respond?

First, we have to do the work of seeing. It’s part of the human response to life that if you peep into a particularly dark place, your instinct is to recoil and look away. But to move beyond a state of survival and stuckness on both an individual and societal level, we first have to face what is.

For me, looking into the darkness has brought two major acknowledgements, things so difficult that, before 2020, it never occurred to me that they would be my concern.

The first is the realisation that liberal democracy, the system of governance to which I I’d been happily married all my adult life, failed in 2020. It is showing no signs of recovery. Liberal democracy is not just about elections; it embodies principles that enshrine a certain conception of life and protect people from the abuse of power. Yet how quickly its core values of freedom of speech and informed consent were abandoned! How devoid the British Parliament of scrutiny! How silent the people about their collective choices! As The Friendly Obituarist writes: ‘what it felt like is something between a failed coup and a dress rehearsal … As we watched, all the institutions of Liberal Democracy were co-opted into this authoritarian project.’

The second realisation is the knowledge that authoritarianism was not just a blip of the twentieth century, a horrible aberration manifesting in Nazi Germany, Stalinist Russia or the Khmer Rouge’s Cambodia that would never happen again. Rather, the tendency to dominate others or to be co-opted into domination is an ever-present possibility of the human psyche. Charles Eisenstein articulates this difficult thought in his final essay on Orwell’s 1984 when he discusses the ‘betrayal of the heart’ that happens when people give up their feelings for their fellow humans in exchange for ‘an idea, a figurehead, the Dear Leader, the Party’.

‘Please do not think that there are two classes of people in this world, those who have betrayed the heart and those who have not. Nearly all of us live a unique permutation of fidelity and betrayal. To the extent we betray ourselves (for to betray the heart is to betray the self) we live in exactly the state Orwell described.’

The twin realisations of the failure of liberal democracy and the ever-present possibility of authoritarianism have been, no contest, the shock of my life. (Although I *should* have known this: I’ve written about Syria, where millions support the Bashar regime, now in its sixth decade.)

I won’t dwell further on these things because this piece is about where we are going and how to respond to the challenges of the coming year(s). First, let’s deal with the responses we don’t want: the psycho-social obstacles that we might put in our own way.

The first response we don’t want is the ultimate non-response: avoidance. This is generally characterised by silence and the failure to think.

The second response we don’t want is denial. This widespread human reaction can be commonly heard in remarks such as ‘oh, that won’t happen,’ in the face of clear evidence or an oncoming trend.

The third response we don’t want is hopelessness. ‘There’s no point. I’m just one person,’ is an expression of such passivity. ‘We can’t do anything. They are so powerful,’ is another. (This, believe it or not, is almost a direct quote from a lifelong Green activist.)

Such statements of ‘the narrative of inevitability’ are part of the crisis we are in. They speak to an abandonment of self-governance on both a personal and a social and political level, an admission that democracy is not participatory, as we once believed, but a mechanism for the handover of power in which everything important is decided by leaders and their chosen associates. Without opposition, in the current context, this approach will take us to a future under Bigger and Bigger Power.

Finally comes a fourth response we don’t want. This one, which can arise when we have already set off on The Road to Change, reminds me of how Christian in The Pilgrim’s Progress has to deal with many unhelpful figures on his way to the Celestial City. It’s the danger, greatly enhanced by social media, of getting stuck at the stage of talking, where we fool ourselves that letting off steam is achieving something concrete in the wider world.

Beyond these responses is the next step, one that leads to more steps and to action that makes a difference. This is the step into empowerment, a mindset linked to action, and a state embodied by the likes of Martin Luther King and Mahatma Gandhi. It involves in fundamental shift in which power is held not by the They but by the We. In the current times, it means going back to basics in practical, psychological and social ways.

So that’s why, amid the ashes of a functioning democracy, I am currently identifying as an anarchist. Not the kind that involves chaos, you understand, but an approach that favours decentralised power and working at the grassroots.

Then I remember that labels don’t matter. Actions do.

In the middle of writing this piece, I had a pertinent reminder that the future is made of micro-choices which come in the course of daily life. ‘I need your finger’. The young woman across the counter pushed an unfamiliar-looking device towards me and I realised that she was asking for my fingerprint.

Standing in the queue to join the local sports centre in Portugal and watching someone press their finger into the device, I’d had a chance to think about my response. I’d already decided I wasn’t giving anyone my biometric data, at least not without considerable thought and for a very good reason. For a few yoga classes and a couple of session in the municipal spa? No way. So I told the young woman she couldn’t have my finger and waited to be denied access.

‘That’s fine. It’s a choice,’ smiled the young woman, and activated my membership card another way. Then I got on with my day, relieved that this particular choice hadn’t involved much sacrifice but alarmed by the ease with which a corporate stranger had requested access to my body.

Life over the next few years will offer many such micro-choices. Together, they’ll create the future for both us and those who follow. To deal with them well, we’ll need greater psychological resilience than in democracy’s complacent days, and an awareness of how we may be being manipulated by those pursuing their own interests.

More positively - and much more fun - is the process of forming new networks and creating new ways of meeting our basic needs. This is perhaps the best forms of protection against the whims of Big Power, offering social and economic resilience in the short and medium term and the basis for a political alternative in the longer term.

Below is a list of organisations, in no particular order and far from comprehensive, that might make useful starting points. They are either international or UK-based and, having arisen in response to the events of the past three years, are fairly new. Feel free to add your own in the comments below or share plans for starting your own networks.

Together has a developing network of local groups to counter anti-democratic policies from government.

Not Our Future’s brand of activism centres on information and conversation.

The World Council for Health has lots of resources and is looking for volunteers.

The People’s Health Alliance has a growing network of community-based hubs.

The People’s Food and Farming Alliance aims to cut out the supermarkets and connect consumers with producers.

The Elevate Network is an online network that may connect you with like-minded others.

UsforThem has supporter groups focused on the wellbeing of children.

The Global Walkout breaks ways of countering growing measures of control down into steps.

Happier New Year Alex!

Here is another site (Zach Bush): https://farmersfootprint.us/

(The word ‘psyche’ in Greek means Soul, so in your text replace it with ‘ego’)

According to mystics, every person born at this time will face all the challenges of our time in his/her life time.

Keep up your spirit, courage, love, compassion, reverence and physical body.

We could but we won't

We should but we don't

We mess with the Earth

Want bounty not dearth

So we take what we can

For self-serving man

We escaped from our caves

But the poor are still slaves

And the rich run the show

As all governments know

All our money is debt

Can't pay it back yet

Farmers murder our soil

While we love to burn oil

You can see with your eyes

It's not very wise

Our kids sure will suffer

when the show hits the buffer

Our lives could be good

How I wish that they would

But our culture is bust

We can't do what we must

So that's why I'm mad

and angry and sad