Whose data is it anyway?

The UK government plans to share a lot of information about YOU.

I’m interrupting my regular Substacking with a somewhat urgent post about a little-publicised development in the UK.

On March 1st a consultation about digital identify verification and data sharing between public authorities comes to a close. Launched on January 4th with almost no media coverage, the proposed changes will spend a short time under public consideration. Should the average person stumble across the consultation and give it only a cursory glance, the changes will likely sound insignificant, just another administrative step along the road to progress in the digital age.

In fact, the proposed changes represent the first stage in creating a centralised digital ID gateway to online public services that will be known as GOV.UK. Under the new system, users will access a portal via a single login and service providers without the need to prove their identity. The idea is that people will only have to provide the details needed to, for example, renew their passport, once. From then on all the public authorities they deal with will know who they are because the data initially submitted will be visible to all of them.

So far, so convenient. But the consultation fail to make clear that, under the proposed legislation, individuals will lose control of data that has hitherto been regarded as personal. The long list of public bodies that will have access to personal information can be found at the end of the consultation documents under Annex B. It includes HM Revenue and Customs, the Land Registry, the Disclosure and Barring Service, the Home Office, departments for Work and Pensions, Justice, Education, Levelling Up, all councils and the major regional authorities.

Crucially, the list also includes ‘any organisation which provides services to a specified public authority in connection with the specified objective’ – a catch-all which presumably covers any company or other body with a contract with a public authority.

By now, the ears of the thinking citizen should be well and truly pricked up: all sorts of organisations can be involved in public service delivery, from large, profit-driven corporations to small charities partially run by volunteers. Government no doubt has agreements with other governments and organisations in other jurisdictions, making the data sharing potentially global. But there’s more. The data includes not just the name, date of birth and address of traditional ID verification but ‘photographic images’, ‘the outcome of identity checks previously performed on a user’ and ‘transactional data, for example, income’.

‘Other data items may be processed as identity verification services develop,’ the text adds. For this, I read biometric data such as finger prints and iris scans and well, just about anything public authorities see fit to request in future.

In short, the proposed data sharing will enable a wide range of public authorities and third parties to build comprehensive profiles of individuals and their behaviour. There is the potential for widespread data breaches. And, in a change of an importance that is hard to quantify, control of the data will have shifted from the citizen to the state.

The current British government has form in creating schemes to avail itself of large amounts of data. In May 2021, NHS Digital launched a new project to collect 61 million medical records from GP records, giving people just weeks to opt out. As this article points out, the scheme created huge potential for data breaches. Have they happened before? Do a quick internet search under the term ‘NHS data breach’ and you’ll find out.

Could things be done differently? It so happens that, while being the least techie of writers, I have a bit of useful background in this area. In 2019, as part of research for a book on European cities that got paused by the Covid crisis, I spent some time in the Estonian capital of Tallinn.

The tiny Baltic nation has developed in leaps and bounds since shaking off the shackles of Russian occupation in 1991 and has been leading the way to the digital society. In Estonia, a state-issued digital ID card is compulsory, and citizens log into a single platform to do all their business, from paying their taxes to getting their medical prescriptions.

The government is so proud of Estonia’s pioneering approach to digitalisation that it created a centre to showcase its work to politicians, journalists and other visiting foreigners. At the e-Estonia Briefing Centre in Ülemiste City, a personable young German told me how the system was built on transparency and trust. A citizen’s data was not held centrally, moving between servers along encrypted pathways so that no one could access it illicitly, Florian said. Every time a public official such as a doctor, police officer or minister checked someone’s data, the search was recorded for the data holder – the citizen – to see. Looking at someone’s secure data for no reason was a criminal offence: ‘The citizens are given the tools to check back up on the government’.

The decentralised system allows the privacy of health records to be maintained. ‘If my doctor gives me a diagnosis that I’m schizophrenic, and fifty per cent of me doesn’t agree with that, I can block it,’ joked Florian, showing me his own record. ‘It’s just visible for me now.’

*

Since 2019, the context around the global trend of digitalisation has changed dramatically. Governments, corporations and supra-national bodies openly discuss new ways of using digital technology to create the kind of human life they think best. Estonia’s vision of the digital society looks rather less liberal than it did pre-Covid: the country was in the vanguard of developing the technology for vaccine passports with the World Health Organisation.

The idea of imposing medical interventions and removing rights through digital means has not gone away. At this year’s World Economic Forum in Davos (also attended by Labour leader Keir Starmer) the UK’s own Tony Blair, a long-standing advocate of digital ID, called for ‘a proper digital infrastructure’ to keep track of people’s vaccination status.

In a 2022 report, according to this media summary, the WEF called for a digital ID based on comprehensive picture of the person to be used as a way of allowing or withholding access to a wide range of services:

‘Once the digital ID has access to this huge, highly personal data set, the WEF proposes using it to decide whether users are allowed to “own and use devices,” “open bank accounts,” “carry out online financial transactions,” “conduct business transactions,” “access insurance, treatment,” “book trips,” “go through border control between countries or regions,” “access third-party services that rely on social media logins,” “file taxes, vote, collect benefits,” and more.’

Gathering the data would be the first step: ‘A data collection dragnet would allow a digital ID to scoop up data on people’s online behavior, purchase history, network usage, credit history, biometrics, names, national identity numbers, medical history, travel history, social accounts, e-government accounts, bank accounts, energy usage, health stats, education, and more.’

*

The Cabinet Office’s timetable for legislation to introduce a centralised system of ID verification and data sharing in the UK is short. Coming to law via statutory instrument (so it’s unlikely there’ll be a Parliamentary debate) the government plans to implement it by the end of this year:

I was so baffled by the brevity of the consultation and lack of media coverage compared to the huge implications of this proposal that I consulted a professional. Talking to Alastair Johnson, CEO of decentralised identity and payments company Nuggets, reassured me I was not going insane. With the data held in a single pot, held by a large and growing number of organisations and no clear vetting procedures for data administrators, he said, the government’s proposed centralised system opens the way for potentially anyone to get hold of your personal details.

‘It’s beyond the data breach problem [where] everyone’s trying their best to keep it secure and then it gets breached anyway. But this is saying: “actually I’ve got an open back door for anyone who wants to come in and get the back door and get the data.” You probably wouldn’t even need to do the security attack, you could just ask to be given access,’ he said. ‘We’re building a ticking time bomb in terms of a data hoard that could be used, abused and breached – even with the best of intentions.’

Prior to the Covid crisis, he told me, the government had been keen to sign up to a decentralised model for verifying identity such as eIDAS, as favoured by the EU and many other countries.

So why, I wondered, the change of heart – and the haste to introduce a centralised system? Johnson suspects that the government may be listening rather too hard to the businesses interested in developing ID verification frameworks – large consultancy firms who are effectively preparing their bids for contracts: ‘You’ve got to be a bit careful about who the consultants are and who they’re prepping up for the next bit of work. Is it truly for the good of all, or is for the good of the consultants?’

A good question. If you’re concerned about the government gaining control of your data, here are some suggestions for Things To Do:

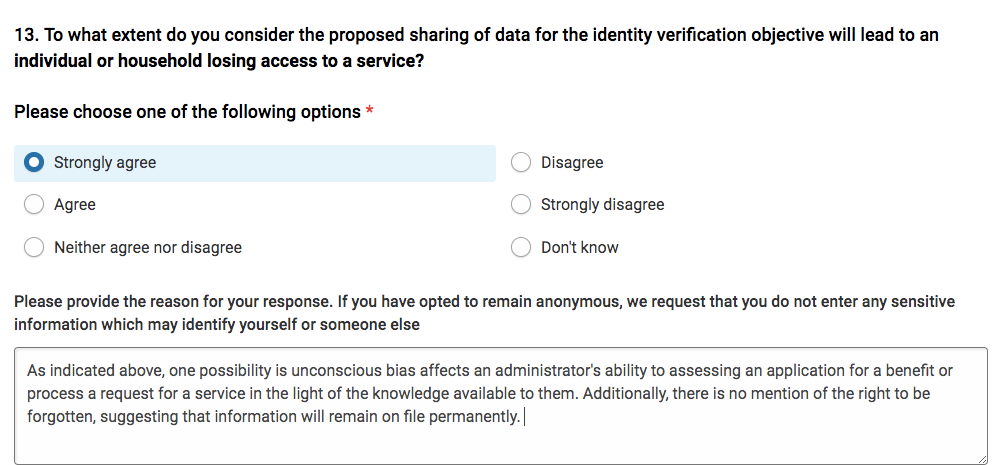

Fill in the consultation. Richard Vobes does a friendly walk-through of the questions here. Although I’m used to reading policy documents and consultations, my own experience of trying to answer the questions was like being wrapped in over-cooked spaghetti. Part of the reason, I think, is that the consultation is not really aimed at the public at all: the phrasing suggests it is essentially designed to elicit a conversation between different public authorities to pick up potential problems of interest to them. When I realised this I felt better for about ninety seconds. Then it struck me how very much that reflects the anti-democratic spirit of the times in which decisions taken on behalf of the general population without much regard for what we think.

Anyway, I recommend ignoring the spaghetti-like qualities of the consultation and focusing on your own concerns. The requests for reasons and examples provide an opportunity to state these. Curiously, the consultation Vobes linked to on his YouTube channel has changed over the past few days, with more questions being added.

Here are my responses to a couple of questions in case they are useful. I deliberately did not spend too long on formulating answers, although in working on this piece I had spent time thinking about my response.

Write to your MP. I know. Over the past couple of years many in Britain have repeatedly said that their MP, when contacted via email or even visited in surgery, shows no interest in hearing views from constituents which are at variance from those they already hold. But despite this show of political insouciance, politicians do actually care – if not about the people they represent, their own position! So a short, to-the-point email can serve as a useful reminder that the power they hold is temporary and conditional.

Share information about the governments plans, whether verbally or by email with any individuals or groups you think might share your concerns. Feel free to share this post – and of, course, to comment below. I write on this subject as a concerned citizen, not a digital expert and welcome contributions from the better-informed.

Finally, forget about this and do something practical that will make you and your household less dependent on public authorities in future. If you didn’t see my last piece, you can find links to suggested organisations to help get started here.

I've done the survey, with the help of https://saveourrights.uk/take-action/digital-id-consultation/

This post is late as I only subscribed to Alex's substack recently. I do feel that the World Economic Forum do want to govern (!!!???) the world and have full dominion over all people. This may or may not be the "cabal" that some people refer to. It seems quite possible that the WEF and their cronies will own practically everything, and the general population will have to rent everything.

“You’ll own nothing” — And “you’ll be happy about it.” Klaus Schwab of the WEF.

For some time I've been on a journey of trying to find things I can actually do in my daily life to resist the destruction of my individual sovereignty and privacy. I don't use smart technology and don't use social media. Also I practice rigorous control of my email inbox and have learnt how to protect my PC and apps from malware, junkware and tracking to a fair degree. This saves time in the long run, and having fewer emails means that email scams are easier to spot. It's taken some work, but also saves time on a daily basis, whilst enhancing security as a spinoff from privacy measures.

It's possible that in the not too distant future the vast majority of routine transactions will only be possible using smartphones. As with card readers, the recipient of the "money" will most likely be charged for the service. Another way of leaching money from people and controlling them at the same time.

"Humans are now hackable animals" Yuval Harari of the WEF.

It could be said that the WEF are predicting the future of the general world population. Hopefully the two quotes given in this post reflect their attitude.

With regard to mRNA vaccines, I don't trust them for "routine illnesses" such as a mild Covid variant. It's becoming common knowledge that mRNA vaccines can cause heart trouble. If I had a lethal cancer, and an mRNA treatment was available, I would accept it on the grounds that the risk would be acceptable. There has been so much secrecy and censoring around these vaccines, coupled with yarns from Western governments that I no longer trust the Government, their appointees or the NHS on medical matters. Regulatory bodies throughout the world also can't be trusted because the vast bulk of their funding comes from Big Pharma.